Commercial crew’s time approachesby Jeff Foust

|

| Amid all the tensions involving the mission, and the commercial crew program in general, the countdown for the launch of Demo-1 went smoothly. |

So, at that hour very early Saturday (or very late Friday night), NASA and SpaceX officials, members of the media, and other spectators gathered at the Kennedy Space Center to watch a Falcon 9 lift off from Launch Complex 39A. What brought them out to the center at that late/early hour was not a typical Falcon 9 launch but instead the start of a critical test flight for the commercial crew program, flying the company’s Crew Dragon spacecraft—without a crew on board—for the first time.

The launch itself, as it turned out, was a bit anticlimactic. Amid all the tensions involving the mission, and the commercial crew program in general, the countdown for the launch of Demo-1 went smoothly, with no technical issues reported and pleasant weather conditions. The launch hit its instantaneous launch window in the middle of night, creating an early dawn on the Space Coast as the rocket lifted off the pad and placed the spacecraft into orbit, with the first stage making what’s become a routine landing on a droneship offshore.

Photographers at the KSC Press Site are silhouetted by the Falcon 9 rocket as it lifted off on the Demo-1. (credit: J. Foust) |

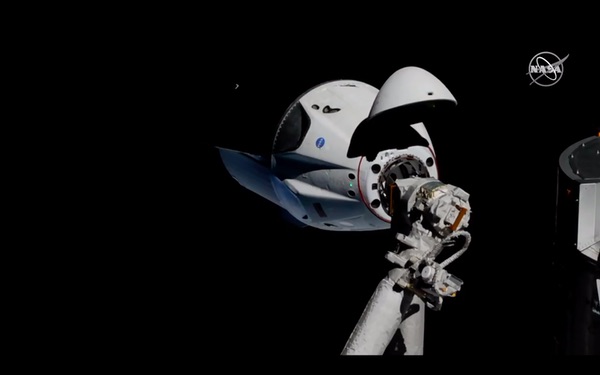

Twenty-four hours later, the scene shifted to the vicinity of the International Space Station as Crew Dragon approached. While the cargo version of Dragon has been going to the station since 2012, those spacecraft approached the station very differently from the new crewed version. The cargo Dragon approaches from underneath—the “r-bar” vector—and comes to a stop close to the station, at which point the Canadarm2 grapples the spacecraft and berths it.

Crew Dragon, by contrast, is designed to actively, and autonomously, dock with the station, maneuvering in front of the station and then closing in on the velocity, or “v-bar,” vector. That new approach was apparently enough of a concern for one ISS partner, Russia, to issue a dissenting opinion during a flight readiness review February 22. Roscosmos was worried that the spacecraft might crash into the station if its flight computers malfunctioned, since there was no separate computer system.

By last Thursday, when NASA held a pre-launch briefing about Demo-1, the agency said it satisfied those concerns. “We agreed with Roscosmos yesterday on a protocol on the approach,” said Joel Montalbano, NASA deputy ISS program manager. That included closing hatches between the port at the end of the station where Crew Dragon would dock and other parts of the station, as well as having the Soyuz spacecraft ready for a rapid evacuation in the event of an accident.

| “These amazing feats show not how easy our mission is, but how capable we are of doing hard things. Welcome to the new era in spaceflight,” said McClain. |

The odds of such an event were “very remote,” Montalbano added, and he was vindicated Sunday morning. Crew Dragon encountered no problems on its approach to the station, at times running about 15 minutes ahead of schedule. It performed its maneuvers as planned, including one where, 150 meters from the station, it stopped its approach and moved back about 30 meters to demonstrate its ability to safely abort a docking attempt in the event of a problem. At 5:51 am EST Sunday, the Crew Dragon made a “soft capture” with the docking port on the station’s Harmony module, and ten minutes later was firmly attached to the station.

Two hours later, the station’s crew opened the hatches and entered the spacecraft. They were greeted by an “anthropomorphic test device”: a mannequin wearing a SpaceX-designed pressure suit and equipped with sensors to measure the environment an astronaut would experience on the spacecraft. (The mannequin, SpaceX announced before the launch, was named “Ripley” after the character in the Alien series of movies.) Also on board was what SpaceX CEO Elon Musk called a “super high tech zero-g indicator”: a plush toy resembling the Earth, sitting on one of the seats. The, ah, indicator did indeed float around while the spacecraft was in orbit, although occasionally getting in the way of the astronauts after they boarded the Dragon.

“Our sincere congratulations to all Earthlings who have enabled the opening of this new chapter in the history of space exploration,” said NASA astronaut Anne McClain in a brief ceremony on the station Sunday after docking. “Congratulations to all of the teams who made yesterday’s launch and today’s docking a success. These amazing feats show not how easy our mission is, but how capable we are of doing hard things. Welcome to the new era in spaceflight.”

The Falcon 9, with Crew Dragon on top, on the pad at Launch Complex 39A during final launch preparations March 1. (credit: J. Foust) |

Schedules and safety

There’s still a lot of hard things to go on the Demo-1 mission. Crew Dragon will remain docked until Friday, when it will depart the station and reenter, splashing down off the Florida coast at around 8:45 am Eastern that morning.

That may be the toughest test yet for the spacecraft. Speaking at a post-launch press conference, Musk said the asymmetric shape of the Crew Dragon backshell, with protuberances to accommodate the Super Drago thrusters for the capsule’s launch abort system, could create a “roll instability” in the capsule as it reentered, while emphasizing that was a low-probability event based on simulations. “I would say hypersonic reentry is probably the biggest concern,” he said.

Even if Crew Dragon aces the rest of the Demo-1 mission—undocking, reentry, parachute deployment, splashdown, and recovery—there’s still work to be done on the spacecraft before it will be ready to carry people. In addition to any issues identified during the mission itself, there are other aspects of the vehicle that need to be taken care of before NASA considers it ready to carry its astronauts.

One set of tasks involves those systems that weren’t needed to meet the objectives of the uncrewed test flight. The Crew Dragon spacecraft on Demo-1 has a scaled-down version of the life support system that will be needed for future crewed missions, said Hans Koenigsmann, SpaceX vice president of build and flight relability, at the pre-launch briefing.

Another missing element is crew displays. “You obviously don’t need crew interfaces unless Ripley’s going to start flying the vehicle,” said Kathy Lueders, NASA commercial crew program manager.

| “You obviously don’t need crew interfaces unless Ripley’s going to start flying the vehicle,” said Lueders. |

The other area involves issues that Lueders said teams had found in the last six to nine months while finishing the Demo-1 spacecraft. One example involves the spacecraft’s Draco thrusters, whose propellant lines have a risk of freezing in certain conditions, based on thermal vacuum testing. That drove the selection of launch windows for the mission, limiting them to those that allowed a one-day transit to the station. Had the early Saturday launch been scrubbed, NASA and SpaceX would have waited three days for the next one.

That will eventually be solved with the addition of heaters to the propellant lines, Koenigsmann said, anticipating no major changes to the vehicle before the crewed Demo-2 mission. “There’s a lot of detail that we have to work through, but in general it’s the same vehicle overall.”

Handling those existing issues, and any new ones found during this test flight, will still take some time. “Even though a lot of progress has been made, there’s still a lot of work that we need to do, and we’re looking forward to working as a team with SpaceX to get that done,” said Pat Forrester, chief of the astronaut office at NASA, at the pre-launch briefing.

Mark Geyer, director of the Johnson Space Center, praised how far NASA and SpaceX have come on Crew Dragon so far, while noting it could be a while before Demo-2 is ready to fly. “I think it’s really incredible how far this team has come in the timeframe they’ve got,” he said Friday. “We’re going to launch when we’re ready, and it could be a bit.”

Elon Musk (left) talks with NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine (second from right) and the NASA astronauts who will fly on the first two Crew Dragon missions to carry people on the crew access arm at Launch Complex 39A, with the Crew Dragon spacecraft flying the uncrewed Demo-1 mission in the background. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

NASA’s public schedule for the commercial crew program lists the Demo-2 mission launching no earlier than July. That mission will come after an in-flight abort test—using the same capsule that flew on Demo-1—scheduled for June. Musk, though, suggested that the test could take place as soon as April, using the Falcon 9 first stage that made its third flight last month launching an Indonesian communications satellite and Israeli lunar lander.

There’s widespread expectation, though, that the July date for Demo-2 will slip, perhaps by months, depending on how much work needs to be done on Crew Dragon to clear it for flying astronauts. Along with the potential for delays by the other commercial crew company, Boeing—whose uncrewed and crewed flights are currently scheduled for April and August, respectively—there’s the worry that neither company will be able to fly astronauts by the end of the year, when NASA’s access to Soyuz seats runs out.

In mid-February, NASA quietly issued a procurement filing announcing its intent to purchase two Soyuz seats from Roscosmos, one for a mission this fall and the other next spring. That would, the agency said, ensure the presence of at least one NASA astronaut on the station through September 2020. Those seats are available, NASA said, because Roscosmos was not planning to use them for its own cosmonauts.

“Past experience has shown the difficulties associated with achieving first flights on time in the final year of development,” NASA stated in the filing. “Typically, problems will be discovered during these test flights. The consequences of no US crew on ISS warrant protection by acquiring additional seats.”

Geyer said the purchase would alleviate any schedule pressure on the commercial crew providers. “We have great confidence in our Russian partners. They have capacity,” he said. “Buying these extra couple of seats allows us to make sure that we’re going to have Americans on board the space station and not have pressure to get up there when we’re not ready.”

Geyer and others at NASA, though, remain hopeful that at least one company’s vehicle will compete its test flights and be certified for operational missions before the end of the year.

| “I think that we will be flying [astronauts], hopefully, this year. I mean this summer, hopefully,” said Musk. |

“There’s a lot that we have to do before we can certify both these vehicles to fly humans to space, but I think it’s a definite possibility, and I’m confident we’ll get one of them up there with crew before the end of the year,” said Bob Cabana, director of the Kennedy Space Center. He estimated a “better than 50 percent chance” of doing so.

“Unless something goes wrong” on Demo-1, Musk said after the spacecraft’s launch, “I think that we will be flying, hopefully, this year. I mean this summer, hopefully.”

Another factor, besides the technical issues with the spacecraft themselves, is an ongoing NASA review of the safety cultures at Boeing and SpaceX, one reportedly prompted when Musk appeared to take a puff of a marijuana joint in a webcasted interview.

That review is ongoing, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said Friday when he appeared at the Kennedy Space Center along with Cabana and the astronauts who will be flying on Demo-2 and the first operational Crew Dragon mission. “NASA has a long history. We’ve been through accidents. We’ve seen them before. We want to make sure that the culture that we have developed over the years as a result of those incidents not just applied to our agency but also applied to our contractors,” he said.

He said he didn’t want to “prejudge any of the results” of that ongoing review, but believed that the review would, in fact, confirm the companies had acceptable safety cultures. “I’m highly confident that our contractors are complying with the terms of their contracts,” he said, “and I expect that we will find that their culture is very safe, and I look forward to reviewing that when the time is right.”

The crew of Demo-2, Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley, have been following closely the development of Crew Dragon, including attending the launch at KSC and then flying cross-country to SpaceX’s Hawthorne, California, headquarters to monitor the docking. Behnken, interviewed on NASA TV after the docking, said it was “super exciting” to see the spacecraft arrive at the ISS. “It’s just one more milestone that gets us ready for our flight,” he said.

And if, for any reason, either Behnken or Hurley are able to fly on Demo-2, one veteran astronaut said he’s ready to step in. “I’d be happy to be out there again going back into space,” said Cabana, a four-time shuttle astronaut. “I’ll be honest: I’d trade places with either one.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.