An enigma behind the curtain: the Tallinn anti-ballistic missile system and satellite intelligenceby Chris Manteuffel

|

| In the case of what was known as the Tallinn System, those uncertainties caused the US to develop more weapons than they would have otherwise, weapons that were in hindsight unnecessary. |

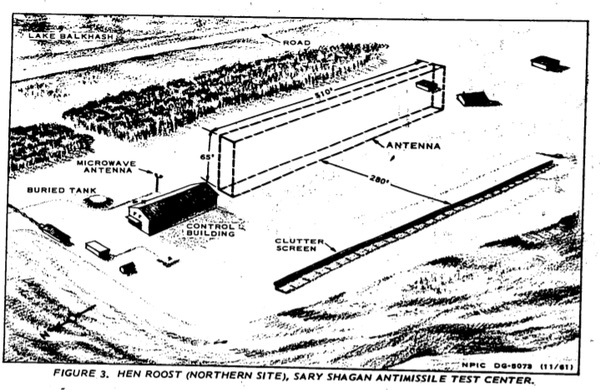

In the first half of the 1960s, the American intelligence community picked up indications that the Soviets were working on anti-ballistic missile (ABM) technology. In April 1960, the last successful U-2 mission over the Soviet Union returned images that showed two large phased-array radars under construction at what the Americans called the Sary Shagan Anti-missile Test Center (SSATC) located on the shores of Lake Balkhash, in Soviet Russia. The radars were positioned to test ABM missiles against missiles launched from the Kapustin Yar missile test site near Stalingrad.[3] Francis Gary Powers’ U-2 was shot down three weeks later, ending that source of information but leaving the Americans desperate to know more. On October 28, 1961, a Soviet nuclear detonation near the SSATC created an unusual atmospheric phenomenon that reflected radio signals past the Soviet border to areas where American monitoring stations could detect them, confirming suspicions that the large Soviet radars the US had designated Hen House and Hen Roost were designed for tracking and targeting ballistic missiles.[4] This nuclear blast was one of a series of high-altitude and outer space nuclear tests around the SSATC, part of a testing program to determine the effectiveness of nuclear weapons in an anti-ballistic missile program.[5] During 1961, the United States further detected three probable ABM launch sites under construction around Leningrad, but construction stopped on the three sites shortly afterwards.[6] US intelligence suspected the Soviets were going to build an ABM system but could not find any operational deployments.

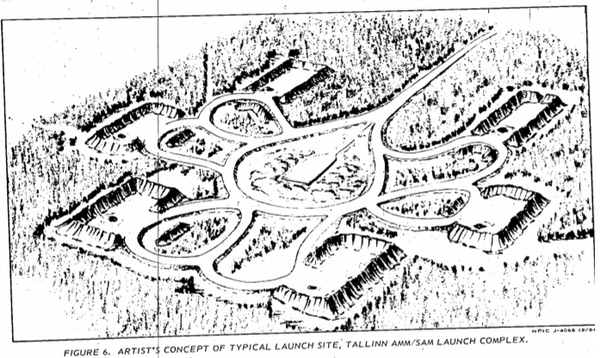

On July 18, 1964, KH-4A Corona satellite Mission 1008 released its second (and last) load of film, eight days after launch.[7] The capsule reentered the Earth’s atmosphere and its parachute was caught and winched in by an Air Force transport aircraft. When analysts examined the film, they quickly noticed two new missile launch sites under construction in a pattern never seen before. One was just outside the town of Tallinn, the capital of Soviet Estonia. Construction there was further along than another site of the same pattern near Cherepovets, a town about halfway between Leningrad and Moscow.

On July 22, just four days after the film capsule was recovered, an alert went out that a new missile system had been discovered. The alert described the site at Tallinn in some detail. There were preparations for five missile batteries, each with six missile launch positions and some unidentified buildings approximately 900 meters (3,000 feet) away, all enclosed by a security fence.[8] Cherepovets seemed to be similar, but the details were not as clear.

Detecting this construction did not resolve any of the intelligence communities’ questions about the missiles themselves. The missiles launched from what was designated the Tallinn System was completely unclear, in large part because there were no parts of any actual weapon system or electronics at either site.[9] The analysts needed more information about the missiles and radars of the system to know what its purpose was; until then it was given the description “AMM/SAM Launch Complexes,” that is, sites that were anti-missile missiles (AMM) and/or surface to air missiles (SAM) launch complexes.[10]

The National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC) released the first in a series of studies in an attempt to answer these questions in September 1964, after KH-7 GAMBIT satellite Mission 4010 took high resolution images of the launch complexes in August.[11] The study drew no conclusions as to the purpose of the system, merely describing the construction, noting that “no missiles or missile-related equipment were identified.”[12] It was a new system, but with only satellite photos of the launch facility under construction—buildings, roads, fences—there was no way to know the technical parameters of the missile or radars.

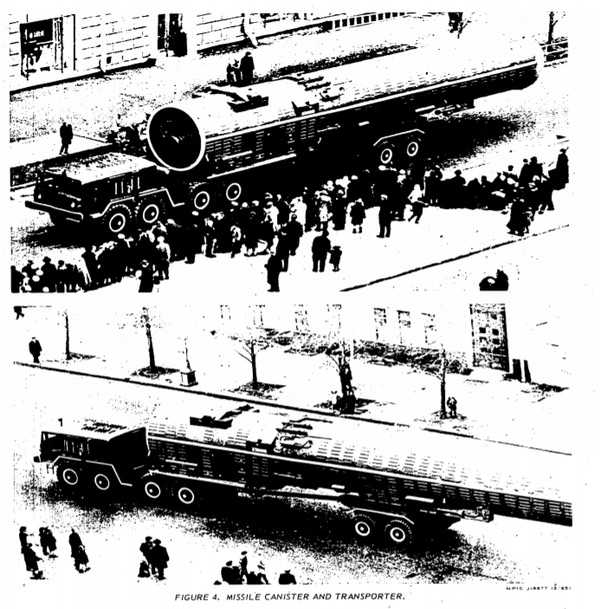

On November 7, 1964, the annual Soviet October Revolution Parade in Moscow gave US analysts their first look at a new Soviet defensive missile. The parade announcer described the missile, which the Americans designated the Galosh (later ABM-1), as one capable of intercepting ballistic missiles “at great distances.”[13] American intelligence analysts confirmed that this missile was truly an anti-ballistic missile, but it was not clear that this was the missile that fit the Tallinn System. In addition to the Tallinn construction, the Soviets had initiated construction of newer, much larger facilities (on a different pattern from the Tallinn work, so most likely a different kind of missile) at several of the antiquated SA-1 missile launch sites around Moscow. American intelligence had no ideas about the missile for these sites either.[14]

In December 1964, the CIA published the yearly National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Soviet strategic defenses. A NIE captures a consensus of the intelligence community and was written (at the time) by the CIA's Office of National Estimates. If the head of an intelligence organization disagreed with the opinion in the main text, he could write a footnote expressing disagreement. Thus, the main text of the NIE generally reflects the position of the CIA director and footnotes allow the heads of other agencies, from the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research to the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) or individual services’ intelligence departments, to express their position. NIE’s are important because they are widely distributed among policymakers, and therefore serves as one of the most important channels by which intelligence would drive broader defense policy.

Illustration of a radar system that was part of the Tallinn site. |

One paragraph of the estimate discussed the possibility that the Tallinn System was part of an ABM deployment. The next discussed what was known about the missile as a SAM. The CIA was willing to state that there “are persuasive reasons for believing that these complexes are related to missile defense.”[15] It seemed a reasonable conclusion because the Soviets were known to be working on ABM technology and this was a new defensive system.

The analysts also looked at what the location of the missile systems signified:

We know of no installations in the vicinity of Tallinn and Cherepovets which call for this selection as early sites for an ABM system or even for a new SAM system.[16]

This was a strong argument that whatever threats it defended against, it was an area defense missile. A shorter-range missile would be placed close to major targets like Moscow and Kiev, not far away. That suggested it was part of a barrier defense of the western Soviet Union from American attack. Tallinn, Cherepovets, and Leningrad (where one of the old Leningrad System launch sites was being adapted for the new system) were all towns over which American long-range bombers and ICBMs would fly if they were heading for the vital targets in the European Soviet Union.

However, with the missile for the launch complex still unidentified, there was no conclusive evidence to confirm anything, just suppositions. The NIE concluded its section on the system with a statement of uncertainty: “any judgment at this time on [the role of the Tallinn System] is in our view premature.”[[17]] Given the tremendous uncertainty, the meager information they had, and the limited conclusions that they drew, there were no disagreements among the heads of any agencies in the 1964 NIE on the nature of the new missile system.

| Given the tremendous uncertainty, the meager information they had, and the limited conclusions that they drew, there were no disagreements among the heads of any agencies in the 1964 NIE on the nature of the new missile system. |

That year, 1964, was also an important year in the US development of Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicles (MIRVs). MIRVs allow one missile to deliver numerous warheads to different targets or, alternatively, to overload the defense of a single target. MIRV made an excellent counter to a large-scale deployment of Soviet ABMs because it would allow the Americans to exhaust the Soviet defenses.

It is impossible to guarantee that most methods for defeating ABM systems, like decoys to confuse or active signals to jam the defensive radars, will work. If the defenses were more capable than the Americans realized, then an American retaliation strike would be defeated and the Soviets would not be deterred from attack. The only way to absolutely guarantee penetration of the Soviet defenses was to launch more warheads than the Soviets had defensive missiles. This was the exhaustion method: if the Soviets had 100 ABM missiles around Moscow, then the Americans would launch 150 warheads at it and be sure of getting at least 50 through.[18] The only way to make that work economically was to fit multiple warheads onto a single missile.[19]

Before 1964, there was reluctance on the part of many in the military to deploy MIRV. Many felt that MIRV technology was nothing more than a cost-saving measure: if the US needed 200 ICBM warheads to deter Soviet attack, and it could put 10 warheads on a single missile, then the US only needed 20 missiles rather than 200, a substantial cost savings. It would be an inferior deterrent, though, because 20 missiles are substantially easier to attack than 200, so a greater percentage of the American warheads would likely be destroyed by an enemy first strike.

After the discovery of the Tallinn System, the defense establishment embraced MIRV technology. “Primary among these [reasons] was the renewed development of missile defense installations observed in the Soviet Union,” wrote one scholar afterwards.[20] Thanks to the requirement to exhaust any potential Soviet ABM system, deploying MIRV technology would now mean that there would still be 200 missiles, only they would carry 2,000 warheads rather than 200, a substantial increase in deterrence—and cost. The decision to deploy MIRV technology was made a few weeks before the NIE was published, in November 1964.[21] It would upgrade the backbone of the American missile force, the land-based Minuteman (the upgrade was designated Minuteman III) and the submarine-based Polaris (the upgraded Polaris was known as Poseidon.)[22]

With two Soviet missile systems under development, it soon became apparent that the system around Moscow (where the Galosh missile would go) was easy to defeat. It simply didn’t have enough missiles to successfully protect Moscow. The never-built full system that the Soviets intended to build would have had only 128 interceptor missiles. This might have been sufficient in 1961, when the US had less than 200 ICBMs, but not nearly sufficient in 1966, when the US deployed over 800 land-based Minuteman missiles and a further 650 sea-based Polaris missiles. In the end, the Soviets only ever built half of the launchers, just 64, because they could see the futility of the system.[23] The Tallinn System was deployed at over 100 locations around the Soviet Union, each with between 18 and 30 individual missile launchers, so even a very modest ABM capability across that many missiles might be able to alter the balance of terror.

This was why a 1968 Senate subcommittee report, one of the most hawkish documents from the Cold War, didn’t think that MIRV was necessary to defeat the Galosh system. This report, which claimed that the main risk to the US was that a “timid, complacent, or overly cost conscious decision maker” would be unwilling to make the “hard decisions” to buy more weapons rather than “desirable non-defense programs”[24] was sure that the Moscow system could be defeated without MIRV.[25]

| What happens under roofs is invisible to cameras, and the Soviets could schedule individual tests around American satellites. |

Because there were no installed equipment or missiles in the new installations at Tallinn, Cherepovets, and Leningrad, US Intelligence had to turn to other sources of information in their hunt for the missiles. In April 1965, the Photographic Intelligence Division of the CIA issued a new study on the Tallinn System, which found that the size of the buildings did not match up with any known Soviet missile to that point. The report noted “the Galosh appears to be too large, and the Ganef [another Soviet missile observed but with an unknown launcher, later designated SA-4] too small, suggesting that the Soviets have one or more missiles we have yet to see in the Moscow parade.”[26] They could not rule out that the Galosh would go into the Tallinn emplacements though, only that it seemed unlikely.[27] Parades were not the only source of information that the CIA tapped. A Soviet propaganda film named “Rockets on Guard for Peace” showed a missile launch, and CIA analysis determined that the missile was a Galosh and geolocated the launch site to SSATC.[28]

Illustration of the Tallinn site. |

That the CIA was only able to learn about Soviet missiles from Soviet propaganda demonstrates a weakness of monitoring research and development programs from satellite photography: what happens under roofs is invisible to cameras, and the Soviets could schedule individual tests around American satellites, effectively hindering American knowledge of their missile development. It was effectively impossible to hide the missiles once they had been deployed, as they needed to sit on the pad ready to fire for days, but during testing and development hiding them was straightforward.

In August 1965, a year after the initial analysis of the Tallinn System had been published, the CIA's Imagery Analysis Division (IAD, the recently renamed Photographic Intelligence Division) put out a routine document, “Soviet Type SAM Installations of the World.” It was nothing more than a list of known Soviet and Soviet-bloc SAM installations. This edition had a very interesting note. Alongside the “Tallinn SAM/AMM Launch Complex” entry there was a remark: “This complex, along with a similar complex near Cherepovets, USSR, forms the beginning of a probable long-range SAM defense system.”[29] This is the earliest position that any organization took on the nature of the missiles in any currently declassified document. This intriguing note does not make clear the reasoning used by the IAD. Other organizations did not follow the IAD’s lead immediately: NPIC, a joint CIA-DIA group, continued to refer to the sites as AMM/SAM launch complexes for another year.[30]

By the November 1965 NIE, more information had been gathered and the battle lines of the debate over the Tallinn System were clearly drawn. The head of the CIA, in charge of the main text of the NIE, presented the Tallinn System as having very limited, if any, capability against ballistic missiles. The DIA, Army, and Air Force intelligence leaders, however, offered footnotes that expressed their belief that “it is more likely that the systems being deployed… are primarily for defense against ballistic missiles.”[31]

Early arguments were over the capabilities of the Back Net and Side Net radar systems associated with the Tallinn System. These were primitive, mechanically scanned radars clearly closely related to other SAM radars. The CIA argued that electronically scanned radars like the enormous fixed phased-array radars then under construction around Moscow for use by the Galosh missile (known in the US by the names Cat House and Dog House) were necessary for any ABM system. Many of the Tallinn System missiles were being deployed beyond the reach of those radars, therefore the missile likely did not have a significant ABM capability, according to CIA analysts.[32]

The defense services, by contrast, argued that:

it is more accurate to state that the Tallinn System is seriously degraded in an area defense role when off-site radar is not provided, but that this degradation does not apply to the Tallinn System operating in terminal defense mode. In the terminal defense mode the defended area is considerably reduced, but the firepower of the complexes and the performance of the on-site radar may be such that the capability to defend the terminal area targets would remain significant.[33]

In February 1966, CIA analysts finally found evidence of a missile at one of the SSATC sites that seemed to be prototypes of the Tallinn System. This missile had a “cluster of at least 3 booster sections” and was about 10 meters (35 feet) long.[34] This suggested that the missile was an ABM: a cluster of boosters suggested great speeds and range, far more than necessary for defending against airplanes. The document also noted at the same time that the Tallinn System sites at Sary Shagan had replaced the SA-2 systems around the SSATC: as the Tallinn style sites came online, SA-2 systems were deactivated.[35]35 This was suggestive that the Soviets expected the Tallinn System to deal with aircraft, as the SA-2 missile was their primary anti-aircraft missile, but did not rule out a secondary capability as a ABM.

The critical year of the Tallinn System debate was 1967. The CIA no longer would admit that the missile, as deployed, had even a modest ABM capability. In August, the CIA released an intelligence memorandum outlining and supporting its position that the Tallinn System was only capable of defending against aerodynamic threats, either airplanes or cruise missiles.

This memorandum outlined several reasons why the Tallinn System was designed for aerodynamic targets and not ballistic warheads. The memorandum first argued that the design of the radar was an evolution of previous SAM systems and not a new design, and was incapable of operating against ballistic missiles.[36] The large radars powerful enough to do that (the Hen House, Dog House, and Cat House radars) didn’t seem to correlate to the Tallinn emplacements, so they seemed to be unrelated.

| The CIA memorandum was just the opening salvo of what would become the most footnote-laden NIE of the Tallinn System debate. |

The second point was a bombshell: a reevaluation of an earlier report. In that February 1966 report on the first missile sighting, the CIA had reported a missile with the cluster of three booster rockets and no wings. This was consistent with an ABM configuration because it suggested a great deal of thrust and no maneuvering in the atmosphere. Apparently, since that initial sighting, only missiles with wings had been identified in the missile launch facilities. This 1967 memorandum now showed that the two were the same (winged) missile viewed from different angles with a shadow that had confused previous analysts.[37] The wings were a sure sign that the missile was intended to operate within the atmosphere, and therefore airplanes were the primary target.

A final argument in the memo was based on a negative: no facilities for storing and handling nuclear weapons had been observed at any Tallinn System installation. Nuclear weapons seemed to most analysts to be a key requirement for the Tallinn System to be an ABM, and the absence of any evidence for that suggested a different role. A nuclear weapon was believed necessary because of the difficulty of intercepting warheads; the missile simply would not be accurate enough for a conventionally armed variant to disable a reentry vehicle. The lack of observed nuclear warhead handling facilities was a strong blow against an ABM capability.

The CIA finally argued that Soviet operational deployment was not consistent with an ABM interpretation. The Tallinn missile was deployed in a similar pattern to the SA-2 missile, providing a long-range air defense barrier for the protection of key Soviet targets. A missile with only limited range (as in a terminal defense ABM system) would not be deployed in such a pattern, because there would be too many gaps.[38]

The CIA memorandum was just the opening salvo of what would become the most footnote-laden NIE of the Tallinn System debate. It established the CIA’s position and developed it in detail. The main text of the NIE merely repeated the memorandum's conclusions that that system, as presently deployed, was only for defense against aerodynamic threats.

In that 1967 NIE, Lt. General Joseph Carroll, director of the DIA, had a “footnote” on the Tallinn System that took an entire page. He agreed that the Tallinn System was primarily for defense against aerodynamic targets, but felt that it was possible the system had a local defense capability as an ABM. From the evidence available at the time, it was impossible to exclude the Tallinn System performing as an ABM, but “on balance [he] believes it is unlikely that the system presently being deployed possesses an ABM capability.”[39] Carroll felt that there was a danger to the US because it could not prove that the Tallinn System targeted aircraft only. The possibility that it was an ABM, while remote, existed, and that was a danger to US security.[40]

After the DIA footnote, the next page was taken up by the intelligence chiefs of the armed services space, each with their own footnote. The Army followed a slightly more aggressive line than the DIA, continuing to argue that those complexes which did have proper radar support could intercept ballistic missiles.[41] The Air Force, however, argued a very different line.

The Air Force footnote agreed with everything that the DIA said:

except that Maj. Gen. Jack K. Thomas [the head of the Air Force intelligence] believes that the Tallinn System was probably designed for and now possess an area anti-ballistic missile (ABM) capability even without inputs from the HEN HOUSE/DOG HOUSE radars.42

Thomas justified himself by arguing that there were many Soviet radar signals that had not been identified by the Americans, and some of them could possibly provide the guidance information that the Tallinn System would need. It is very difficult for satellites to classify radars. Generally, satellites could record radar signals, and they could take pictures of the radar antenna, but they could only rarely capture enough of a signal to understand the full capabilities of a system.[43] Even as late as the mid-1970s, the US had no records of the radar signals for a Tallinn System missile engagement; they had records of the radar tracking targets, but the only evidence of what a launch would be like was based on photographs. Without that information it was difficult to determine the capabilities of the system.[44] This limitation was a major source of uncertainty regarding the Tallinn System.

Thomas’ footnote further argued that the Tallinn missile was capable of exo-atmospheric intercepts over 110 kilometers (70 miles) away. He based this range on “the configuration of the Tallinn missile, if in fact this element of the Tallinn system is correctly assessed.”[45] This was the most extreme position ever taken on the Tallinn System in a NIE footnote. In this footnote the Tallinn System had not just a limited capability against ICBMs, as most other Defense Department arguments went, but was a fully capable area defense system.

The Navy’s footnote read, in its entirety: “Admiral E.B. Fluckey [head of Naval intelligence] believes that the Tallinn system has negligible capabilities against ballistic missiles.” The Navy clearly agreed with the CIA on the Tallinn System.

In the aftermath of the 1967 NIE, one CIA officer wrote an internal memo analyzing the “remarkable outpouring of footnotes on the Tallinn System in [NIE] 11-3-67.”[46] He pointed out the major influence that outside agendas had on organizational positions. The DIA served both the Joint Chiefs of Staff, a group that supported construction of an American ABM system, and the Secretary of Defense (Robert McNamara) who did not. That explained, according to the CIA officer, why the DIA took a position which essentially agreed with both sides, that the missile was unlikely to be an ABM, but could be upgraded to be one. The Army, which would run any American ABM system, supported the idea that the Tallinn System could be used as an ABM.

Likewise, Air Force analysts took such an extreme position, according to this memo, because the Air Force would be responsible for defeating the system, and so it was only natural that it would have the strongest interest in the system. The memo suggests both a bureaucratic reason and a more noble reason why the Air Force would take such an extreme position. The Air Force budget (and power) would obviously be enhanced with the deployment of a new weapon system, in this case the Minuteman III.[47] The Air Force, however, also had been given the mission of ensuring that their missiles penetrated and destroyed any target that they were tasked to hit, and in that context it would also be natural for them to be more worried than other services about ABM systems.

| In the aftermath of the 1967 NIE, one CIA officer wrote an internal memo that pointed out the major influence that outside agendas had on organizational positions. |

The Soviet defensive systems faced in the direction of the American Midwest, where the American land-based missiles (and bombers) would come from. Common operating areas for American missile submarines, much closer to the Soviet Union, were not covered.[48] That meant that the Navy was much less affected by the Tallinn System, and so didn’t care.

The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in 1967 was an Army General named Earle Wheeler. He had been an infantry officer for most of his career, serving as the chief-of-staff of the 63rd Infantry Division in World War II.[49] He testified to a Senate subcommittee that the US needed to deploy MIRV missiles based on the threat of the Tallinn System. He said that there was “some divergency of views” on the capabilities of the Tallinn System, but that he personally found it “difficult to accept” that it was just for air defense.[50] He did not provide any further support for the threat than that in the unclassified session, but urged further development of MIRV technology.

By the time of the 1968 NIE, the debate had shifted once again. By this point even the Air Force and Army admitted in their joint footnote, that “it is highly probable that the [Tallinn] system was developed to provide an atmospheric intercept capability against medium and high altitude aircraft, air-to-surface missiles and submarine launched ballistic missiles [SLBM].”[51] But those two military services still felt that the Tallinn System had to have at least some ABM capability. As the footnote explained, “an estimate that some of the [Tallinn System] complexes are intended to function in an ABM role gains credence from the large and growing Soviet investment in this new system at a time when missiles rather than manned aircraft pose the largest” threat.[52]

What that argument missed was that the Soviets might not be reacting to the threats of 1968; they could be reacting to the threats of a decade earlier, when the Tallinn missile program began. The American B-70 Valkyrie bomber was exactly the sort of high-altitude, supersonic threat that the Tallinn System would be quite effective at engaging if the CIA was right about its capabilities.[53] The US had long before canceled the bomber, but the Soviets might still be deploying a system to defeat it.

The argument receded over the next few NIEs, with the two military services weakening their objections, year-by-year, until the 1971 NIE, which had no footnoted objections to the main text’s characterization of the missile as a surface-to-air missile.[54]

But even the 1968 NIE, published in October 1968, was too late to have any influence on MIRV deployment: the first operational tests of MIRV missiles were conducted on August 16, 1968.[55] This was a scant four years after the missile program was jump-started by the discovery of the Tallinn System, evidence of the high priority that MIRV had during this period. The first group of Minuteman III missiles was operational in 1970 and the first Poseidon missiles became operational in 1971, showing clearly how much effort was put into deploying the technology.[56] The Minuteman III acquisition program alone cost around $12 billion, when in 1965 the entire US annual defense budget was $51 billion, so this was a significant expenditure.57

A 2006 satellite image of the Tallinn site via Google Earth, showing the missile battery access roads and launch emplacements still visible in the snow over 40 years after they were built. (credit: DigitalGlobe) |

The Tallinn System missile, eventually designated the SA-5 “Gammon” by NATO (known as the S-200 Angara to the Soviets) survived the downfall of the Soviet state that created it. Exported to numerous Warsaw Pact countries along with India, Iran, North Korea, Libya, and Syria, the missile is still in service today in many of those countries, and in Russia itself.[58] In 1986, Libya fired several of the missiles against US aircraft (all missed, and the US bombed the launch sites in retaliation), and some claim that the missile was fired several times at SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft, again without a hit. Some of the missiles came under NATO control when East Germany unified with West Germany in 1990.[59] From all this information the capabilities and limitations of the Tallinn System became clear: the missile was not capable of intercepting ballistic missiles.

| The Tallinn System demonstrates that while it was capable of answering many questions, taking pictures from outer space was not sufficient to answer all the important questions. |

In 1967, President Lyndon Johnson praised the output of the spy satellites, claiming that their lesson was that “we were doing things we didn't need to do. We were building things we didn't need to build. We were harboring fears we didn't need to harbor.”[60] At the exact same time that he crowed about the success of overhead intelligence at cutting back spending on wasteful weapons systems because of enemy quantity, he had approved budgets spending enormous sums of money to protect against uncertainty about enemy quality.

The Tallinn System demonstrates that while it was capable of answering many questions, taking pictures from outer space was not sufficient to answer all the important questions, and that uncertainty continued to drive defense acquisition programs. By providing immediate indications that something new was coming, but not where the new missiles were going to be deployed nor what the limitations of the system were, spy satellites were just as capable of starting arms races as ending them.

Acknowledgement

Special thanks to Jeff Hartley of the National Archives, to Professors Mel Leffler and Gerald Haines of the University of Virginia (who taught the class this paper was originally created for), and to Andrea Manteuffel, Rachel Manteuffel, Dr. Byron Knight, R. Cargill Hall, and Dwayne Day for their invaluable assistance with this project. All errors are the author’s.

Endnotes

- Siddiqi, Asif. Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1975. NASA History Division: Washington DC. 2000. One of the four pads was for space launch purposes, only three of them were military.

- The US still added over a thousand missiles to their arsenal, just not as many as they would have otherwise. This left the Soviets even further behind and even more desperate to catch up.

- Brown, Donald. “On The Trail of Hen House and Hen Roost.” Studies in Intelligence Spring 1969. RG 263, NARA

- Ibid.

- Zaloga, Steven. The Kremlin's Nuclear Sword. Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington DC 2002. p. 99 Hereafter KNS

- Thomas Wolfe (RAND executive). Scope, Magnitude, and Implications of the U.S. Antiballistic Missile Program. Hearings before the Military Applications Subcommittee of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, November 7, 1967. Published by the General Printing Office. Hereafter GPO.

- In this era before digital cameras, film had to be returned to Earth in buckets; as a consequence there tended to be many short-lived missions. In this era, US satellites tended to operate for a week every two-three weeks, lifetimes gradually extended over the course of the project.

- “Suspect AMM/SAM Complex: Tallinn USSR”, Record Group 263, National Archives and Record Administration. Hereafter RG 263, NARA.

- The missile system went through many different names over the years. At first it was the Tallinn System, then for a while NPIC called it the AMM/SAM while the CIA named it the Probable Long Range SAM. Eventually NPIC adopted the name Probable Long Range SAM, and then in 1968 it was given the designation SA-5. To avoid confusion it will be referred to as the Tallinn System throughout.

- “Updating of AMM/SAM Launch Complexes.” CIA Research Tool, National Archives. Record Group 263. (Hereafter cited as RG 263, CREST, NARA) April 28th 1965. The term Anti-Missile Missile was replaced by the term Anti-Ballistic missile later for some unrelated reasons.

- “Tallinn AMM/SAM Launch Complex and Cherepovets Suspect AMM/SAM Launch Complex.” RG 263, CREST, NARA, September 1964.

- Ibid.

- National Intelligence Estimate 11-3-64: Soviet Air and Missile Defense Capabilities through mid-1970. RG 263, NARA, December 1964. Hereafter all such documents are referenced as NIE 11-3-xx.

- Ibid.

- NIE 11-3-64

- NIE 11-3-64

- NIE 11-3-64

- Dr. John Foster, Director, Defense Research and Engineering (hereafter Foster). Scope, Magnitude, and Implications of the U.S. Antiballistic Missile Program. Testimony before the Military Applications Subcommittee of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, November 6, 1967, GPO.

- Competent use of MIRV would mean that one interceptor could not hit multiple warheads.

- Greenwood, Ted. Making the MIRV. Ballinger Publishing Company: Cambridge, MA. 1975. p. 40. Hereafter referenced as MtM.

- Ibid. p 6.

- Ibid. p. 49.

- KNS, p. 154

- Investigation of the Preparedness Program. Report by the Preparedness Subcommittee, Senate Committee on Armed Services. 90th Congress, 2nd Session. GPO, Washington DC, 1968.

- The report urged the acquisition of MIRV technology, to be sure, but due to the uncertainty over the capabilities of the Tallinn System, not the Galosh system. At that point, however, MIRV technology was almost ready to be tested, and was not in any danger of being canceled.

- “Comparison of Tallinn, Leningrad, and Sary Shagan Launch Positions”, CREST, RG 263, NARA

- Ibid.

- “Suspect GALOSH Launch Site From 'Rockets on Guard for Peace' (Soviet Source)”, CREST, RG 263, NARA

- “Soviet Type SAM Installations of the World” CREST, RG 263, NARA

- “Liepaja AMM/SAM Launch Complex, USSR” CREST, RG 263, NARA and “Construction Chronology of Deployed Probable ABM and Long Range SAM Launch Complexes”, CREST, RG 263, NARA

- NIE 11-3-65, RG 263, NARA, November 1965.

- NIE 11-3-66, RG 263, NARA, November 1966.

- Ibid.

- “P.I. Notes 18 February 1966” CREST, RG 263, NARA

- Ibid.

- “The Performance and Deployment of the Tallinn Missile System”, RG 263, CREST, NARA, August 1967.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- NIE 11-3-67, RG 263, NARA, November 1967.

- The DIA footnote also opened up what would be the next argument about this missile. Upgrading surface to air missiles (not just the Tallinn System but the older SA-2 as well) to achieve ABM capability was to consume a significant amount of attention into the mid 1970’s.

- NIE 11-3-67, RG 263, NARA, November 1967.

- Ibid.

- This was one area where replacing the U-2 with satellites was not a positive development. The Soviets would use all of their radars to track a U-2 flying over their country, so it was easy to learn about new radars. This could not be done by satellites, so more difficult means like looking for signals bounced off the Moon became necessary. For details on the moon bounce methods, see Eliot, Frank. “Moon Bounce ELINT”. Studies in Intelligence, Summer 1967. RG 263, NARA.

- “The SAM Upgrade Blues” by Sayre Stevens. Studies In Intelligence, Summer 1974. RG 263, NARA.

- NIE 11-3-67, RG 263, NARA, November 1967 It is unclear if this is a reference to the already withdrawn CIA claim of two different missiles, or a reference to another argument that has not been declassified.

- “DIA and the Service Intelligence Agencies,” RG 263 CREST, NARA, Undated unsigned draft.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- General Wheeler is one of the central characters in H.R. McMaster’s Dereliction of Duty, about the moral and leadership failures of the Joint Chief’s of Staff in the Vietnam War.

- General Earle Wheeler, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. U.S. Armament and Disarmament Problems. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Disarmament, Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, February 28, 1967.

- NIE 11-3-68, RG 263, NARA, October 1968. SLBM’s generally move slower than ICBM’s, so they are easier to engage. However, the Tallinn defensive belt was not orientated towards Polaris operational areas, so they did not seem to pose much threat.

- Ibid.

- “The Soviet SA-5 Deployment Program.” RG 263 CREST, NARA. June 1969.

- NIE 11-3-69, NIE 11-3-70, NIE 11-3-71, RG 263, NARA.

- Tammen, Ronald. MIRV and the Arms Race: An Interpretation of Defense Strategy. Praeger Publishers: Washington DC 1973. p. 89.

- MtM, p. 10

- “Worldwide Military Expenditures and Related Data, Calendar Year 1965” Economics Bureau, United States Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, US Department of State.

- Cullen, Tony and Christopher Foss, eds. Jane’s Land Based Air Defense. 10th Edition. Jane’s Information Group: Alexandria VA. 1997.

- Ibid.

- Taubman, Philip. Secret Empire: Eisenhower, the CIA, and the Secret Story of America’s Space Espionage. Simon and Schuster: New York. 2003.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.