Human spaceflight, exploration and the jobs specterby Roger Handberg

|

| Human spaceflight has no independent justification because, to this point, everything accomplished in outer space can be accomplished by robotic means. |

Economic exploitation of outer space builds on the understanding that, from low Earth orbit, many things become possible for commercial purposes. Communications and remote sensing, joined by space navigation, were the early forerunners of such efforts. These initial tasks did not require a human presence, a fact still relevant for most space commerce activities. Space tourism is much discussed, but the practical issue of affordable and dependable access to and from space has delayed progress. Regardless, this perspective minimizes the human space exploration aspect of space activities.

Perhaps most importantly, the third perspective focuses on the security uses of outer space, all which are currently provided through uncrewed missions with no apparent loss of effectiveness. The point is that each of these perspectives is not hostile to human space exploration but places that as a lower priority. As a result, resources in their view should go toward their priority.

The order with which each perspective appears is the result of a specific state’s history and vision of itself. They shift in importance over time: nothing is static, and a mix of views will appear and fade away depending on events. So, for China, national security was the original driver, while in India, space activities of political necessity had to be tied to social and economic development. While both states have moved on since that original period, the earlier perspective merely fades but does not disappear.

The ultimate justification

Human spaceflight has no independent justification because, to this point, everything accomplished in outer space can be accomplished by robotic means. The original Earth-orbiting satellite proposals, such as the 1945 article by Arthur C. Clarke, had humans on board to complete tasks now carried out by comsats and remote sensing systems. (The US, around the same time, rejected a proposed Earth-orbiting satellite because it was not a weapon; therefore, had no military purpose.) Both these functions do not require humans. In fact, humans add immense costs and other requirements simply to sustain their lives on board the spacecraft. Humans can make a difference in space operations because of their adaptability to changing circumstances. Not every contingency can be solved remotely, so the question becomes what justifies the presence of humans on a mission given the heightened costs and additional support technologies.

| The stark reality is that this mix of the sacred and the profane keeps US human space exploration moving forward. |

In the short term, the justification that sustains US human space exploration comes down to jobs, specifically constituent jobs. Other justifications embodied in the theme of human nature and the quest to explore the unknown are often heartfelt by their articulators, but are not the critical factor. Space politics in the United States is a priority for few either in the public or Congress. Linking activities to constituent jobs brings in the additional political support necessary for continuation.

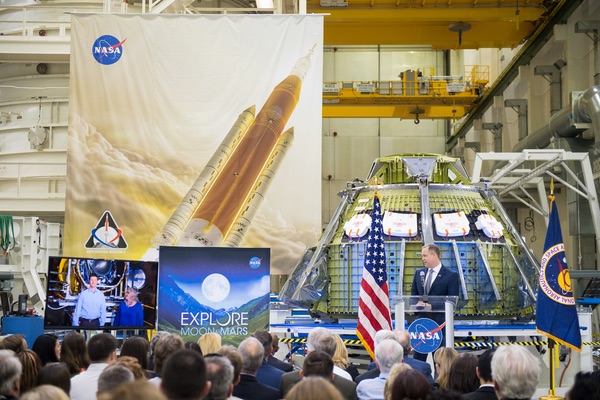

That linkage allows NASA to overcome its failures: Apollo 1, Challenger, Columbia, and the interminable delays developing the Space Shuttle and the Space Launch System (SLS). Approval of the shuttle program in 1972, the X-33 program in 1996, and the SLS in 2011 were all premised on jobs, in California for the first two and more generally for the third. The great unknown is whether the first two would have been approved absent that justification, given both were during presidential election years.

This reality does not negate other motivations, especially the frontier concept or the more general human quest to understand the unknown. The stark reality is that this mix of the sacred and the profane keeps US human space exploration moving forward. The earlier insult mocking the SLS as the “Senate Launch System” was a backhanded compliment to the two senators (Kay Bailey Hutchison from Texas and Bill Nelson from Florida) involved. They took the tools available to keep human space exploration on the national agenda. Both are gone from office but the program moves on. Recent events put the SLS in jeopardy, but NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine reaffirmed the agency’s commitment to SLS (see “Rethinking EM-1, and SLS”, The Space Review, March 18, 2019.) He has no choice, given political realities.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.