The ghosts of flagships past and futureby Jeff Foust

|

| “I think we still have adequate schedule reserve to get to that March 2021 date,” said Ochs, despite issues that used up JWST schedule reserve recently. |

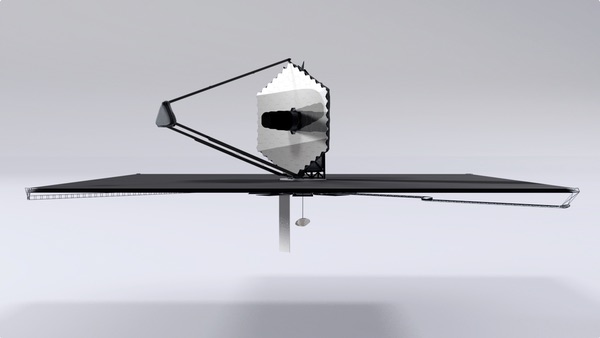

The bad news, though, is that while Astro2020 weighs those proposals to determine what will be the top-ranked flagship mission for the 2020s, those identified as the top-ranked flagship missions in the 2000 and 2010 decadal surveys have yet to fly. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), picked in 2000 when it was known as the Next Generation Space Telescope, is still undergoing testing because of technical issues, and resulting delays and cost overruns, that have pushed its launch back to March of 2021. The Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), the top flagship mission concept from the 2010 survey, may never fly, as NASA, for the second year in a row, has sought to cancel the mission in its budget request.

For JWST, officials at NASA and prime contractor Northrop Grumman say that the program is adhering to its revised schedule announced last June. The spacecraft part of JWST—the bus and sunshield—recently entered a thermal vacuum chamber for a test that will run until next month. By this summer, that spacecraft element will be ready to be integrated with the optical element, consisting of the mirrors and instruments, and then begin a final round of testing that will extend into next year before it’s shipped to the launch site in French Guiana.

There are still concerns, though about the overall schedule for the mission. At a meeting last month of the Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics of the National Academies’ Space Studies Board, Tom Young, who chaired the independent review board that examined the state of the program last year, weighed in on how well NASA had done in implementing the board’s recommendations. By and large, he concluded, NASA had done a good job.

One issue he had, though, was schedule. “We went back and took a look at schedule performance as a part of our assessment,” he said. “One thing really did catch our attention and that was, in our judgement, that the consumption of margin at the time we looked at that was significantly higher than we would have expected.”

The margin he was referring to was schedule margin built into various parts of the revised schedule for the program. Young said that some “back-of-the-envelope looks” at the schedule created some concern for him. “Reserves had been consumed at a pretty high rate and the impact of that should really be better understood and analyzed,” he concluded.

NASA officials, both at that meeting and subsequent events, downplayed the schedule risk. “I think we still have adequate schedule reserve to get to that March 2021 date,” said Bill Ochs, NASA JWST project manager, during a town hall meeting about the mission April 10 at the 35th Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Ochs said that during recent vibration tests of the spacecraft element, the program used up “a chunk of reserve” during testing on one axis. “Once we got through that on the first axis, the other two axes just clicked off,” he said. “That’s what really took up the most of that reserve that Tom [Young] was referring to.”

A report last month by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), released the same day that Young spoke at the Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics meeting, also raised schedule concerns, noting the mission was already a week behind its schedule as of last November and was entering what it termed its “riskiest phase of development” in the form of integration and test.

NASA accepted the recommendation of the GAO report that it update a detailed cost and schedule assessment, known as a joint confidence level, prior to the mission’s system integration review scheduled for August.

WFIRST, meanwhile, is caught in a budgetary tug-of-war between the administration and Congress. NASA sought to cancel the program in its fiscal year 2019 budget request last year, but Congress rejected that proposal and instead allocated $312 million for WFIRST.

| “If James Webb isn’t yet ready, preparing WFIRST right away is probably not the right approach,” Bridenstine said. |

The problem, though, was that funding was about $60 million less than what NASA had previously projected for the mission in order to keep it within a $3.2 billion cost cap and launch in 2025. “This does mean that $60 million worth of work that they had been planning to do in FY ’19 is being deferred into later years, which has an impact downstream,” Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said at the Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics meeting last month.

He said the mission can stay on track if Congress provides full funding for it in its fiscal year 2020 appropriations bill: $542 million, Hertz estimated. If Congress rejects the proposal to cancel WFIRST, but provides less than $542 million, he said NASA will face two choices. “We will have to choose between either blowing the cost target and having a larger run-out cost because we had to slow down, or descoping something significant,” he said.

The only significant thing that can be descoped, or removed, from WFIRST, is its coronagraph, an instrument designed to precisely block light from individual stars, allowing the telescope to observe planets or circumstellar disks orbiting them. That instrument had already been scaled back to a technology demonstration when NASA revised the mission to fit into that $3.2 billion cost cap.

NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine has defended the decision to cancel WFIRST, saying the agency can’t afford to develop it while also working to get JWST on track and maintaining an overall balanced research program. “If James Webb isn’t yet ready, preparing WFIRST right away is probably not the right approach,” he said at a hearing of a House appropriations subcommittee last month.

At an April 2 hearing of the House Science Committee, he again defended the decision to cancel WFIRST. “Why does it make any sense to take WFIRST out of our budget?” asked one committee member, Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA).

“What I’m hoping to work with you on is a balanced portfolio,” Bridenstine responded. He argued trying to do WFIRST while JWST was in development would “cannibalize” smaller missions and research programs. “When we do that activity, we put a lot more risk on the entire astrophysics division.”

Beyer didn’t appear to be convinced. A day after the hearing he issued a press release where he said he had asked appropriators to provide “at least $542 million” for WFIRST in 2020, the funding level previously identified as necessary to keep the mission on schedule. “WFIRST and other top scientific priorities at NASA deserve support and funding from Congress,” he said in the statement, “and I will continue to push for the successful development of these missions.”

Carpe posterum

Bridenstine’s toughest audience about WFIRST, though, is the astrophysics community. A day before testifying before the House Science Committee, he spoke at an astrophysics workshop in suburban Washington where he addressed, among other things, the decision to cancel WFIRST.

“It is in essence the casualty of James Webb,” he said. He emphasized that work on the mission was continuing this year with the $312 million in funding Congress provided for the current fiscal year. “While the budget request may zero it out, what we do at NASA is we follow the law. And if the law says we’re going to do WFIRST, guess what? We’re doing WFIRST, and we’re going to do it with everything we’ve got.”

| “If we continue to do the same things that we’re doing, we have an unsustainable future,” argued Arenberg. |

That workshop was a three-day event held by the Universities Space Research Association titled “The Space Astrophysics Landscape for the 2020s and Beyond” intended to examine mission concepts, and key science questions, ahead of Astro2020. The meeting included presentations on the four flagship mission concepts being studied—HabEx, LUVOIR, Lynx, and Origins Space Telescope—and a larger number of medium-class “probe” mission concept studies, as well as talks on scientific topics from cosmology to exoplanets.

Other sessions, though, addressed issues such as spacecraft technology, including the ability to assemble or service future observatories in space, as well as estimating cost. Those sessions brought out some of the most spirited discussion about the feasibility of proposed missions given budgetary and policy issues.

Many argued that the way that flagship missions are developed needs to change. “If we continue to do the same things that we’re doing, we have an unsustainable future,” argued Jon Arenberg of Northrop Grumman, extrapolating projections of cost and schedule of flagship missions during one conference panel. If current trends continued, it would take so long, and cost so much, to develop such a mission that there will be no appetite to do so, he said.

To break that trend, he called for budgets that grow in real dollars as well as moving away from an “artisanal” model of building one-off missions to approaches that make use of a “series of missions that builds technology, expertise, personnel, hardware, economic interest, and political support that leads to a successful program.”

“Randomly picking things, at least from an engineer’s view, for the ‘science of the week’ is not a way to secure our future,” he said.

Another panelist agreed “The current paradigm is not sustainable,” said Lisa Storrie-Lombardi of JPL. There are ways to cut mission costs and get good science, she argued, such as Spitzer, which lowered its cost from $2.2 billion to $800 million through a series of design changes that still resulted in a highly successful mission. She added, though, that this approach won’t work in every case.

Another way out of the current paradigm, she said, could be through the use in-space assembly for large space telescopes. “That looks to me like a path,” she said, despite the near-term costs and technological challenges. “On a 30-year timescale, it could provide us a path to huge telescopes and get us out of the too-big-to-fail model.”

Alan Dressler, an astronomer with the Carnegie Observatories, said that astronomers need to avoid repeating the experience with the 2010 decadal survey that recommended WFIRST. That study was faced with what he said was a “less than $2 billion budget envelope” for new missions, and many of the missions it considered were too expensive.

“Instead, we found three programs, all proposing the same hardware, a one-and-half-meter telescope, that together were considered a worthy mission,” he said. Combined, those efforts to study dark energy, detect exoplanets through microlensing, and perform wide-field imaging, became WFIRST.

The mission has since grown, both in cost and ambition, in part because NASA gained access to a 2.4-meter telescope from the National Reconnaissance Office it now plans to use for WFIRST. “The new WFIRST is an excellent mission, a powerful mission, far better than anything that we had imagined,” he said.

That came at a cost, though, beyond WFIRST’s increased price tag. “What has been lost is an opportunity to start one of the flagship missions early in the 2020s,” he said. One of the reasons behind that original small cost envelope for the 2010 decadal, he said, was the ability to start a mission from the 2020 decadal early. He suggested WFIRST might have been better carried out as a $2 billion cost-capped mission, allowing it to be done faster and freeing up budget to start the next flagship sooner.

| “The science should drive the program, not the budget,” said Hertz. “If you assume you’ll have a small budget, you’re going to have a small program.” |

The Astro2020 committee is not likely to face the strict budget envelope of the 2010 decadal. In a presentation at the beginning of the workshop, NASA’s Hertz projected that there was about $5 billion in the astrophysics budget available over the next decade for strategic, or flagship, missions. That could grow to as much as $7 billion if budgets grew with inflation, he added.

He cautioned the committee, and astronomers in general, from being too pessimistic about the future, despite the problems faced by JWST and WFIRST. “Seven billion dollars a decade is a lot of free energy for a decadal survey committee to play with,” he said. “The decadal survey committee should not be scared of big missions because they cost a lot. They should think about what is the science that we need to do, and what are the missions that we need to do that science.”

At the workshop, and the earlier Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics meeting, Hertz rolled out a phase that outlined his philosophy for the upcoming decadal: Carpe Posterum, or “seize the future.”

In a panel session at the end of the workshop, he went so far to say that all four of the flagship missions being studied for Astro2020 should be flown at some point. “We’re not picking which mission we’re going to do, we’re picking which mission we’re going to do first,” he said, calling the four missions under consideration the “next generation of Great Observatories,” the name applied to the Hubble Space Telescope, Compton Gamma-ray Observatory, Chandra X-Ray Observatory, and Spitzer Space Telescope.

“The decadal survey committee should be ambitious,” he said. “The science should drive the program, not the budget. If you assume you’ll have a small budget, you’re going to have a small program.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.