NASA’s plan for a human lunar landing in 2024 takes shapeby Jeff Foust

|

| “It fits on paper and it looks like it’s something we can go do, but I will tell you it is not easy and it is and it is not risk-free,” Gerstenmaier said. |

That is, at least, the plan that is taking shape at NASA to achieve the new goal, announced nearly six weeks ago by Vice President Mike Pence, of landing humans on the south pole of the Moon within five years (see “Lunar whiplash”, The Space Review, April 1, 2019). While it wasn’t a surprise that Pence sought to accelerate previous NASA plans, whose 2028 date for a human return was criticized for being too slow, few expected Pence to bring forward the deadline by that much. Surely NASA must have a plan for achieving that goal, right?

So the space industry, as well as members of Congress, waited to see that plan, and its corresponding budget. And waited, and waited some more. It wasn’t until last week until NASA started providing some of the details about how it could pull forward a human lunar landing by four years.

“We’re off building that plan,” said Bill Gerstenmaier, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, during a presentation last Tuesday at a joint meeting of the Space Studies Board and Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board of the National Academies. “It fits on paper and it looks like it’s something we can go do, but I will tell you it is not easy and it is and it is not risk-free.”

The plan he sketched out at that briefing starts little different than the current program of record, involving continued development of the SLS and Orion. Nearly two months ago, NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine said that NASA was considering moving Exploration Mission 1 off of SLS, launching Orion on some combination of commercial rockets, only to say at the National Space Council meeting where Pence made his announcement that the agency was sticking with SLS.

Instead, NASA has been studying ways to accelerate development of SLS to overcome schedule delays caused primarily by issues with the core stage of the rocket. That has included a switch from vertical to horizontal integration of core stage elements so that components can be assembled while dealing with problems with the engine section of the rocket.

Also up for discussion is whether to conduct a “green run” test of that core stage, which involves shipping it from the Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans, where it is assembled, to a test stand at nearby Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. There, the core stage would be fired on a test stand for eight minutes, simulating a complete flight of the vehicle. Bridenstine, in testimony at a House hearing the day after Pence’s speech, suggested the green run could be replaced with a brief static fire of the vehicle on the pad at KSC.

The proposal to skip the green run has raised safety concerns. “There is no other test approach that will gather the critical full-scale integrated propulsion system operational data required to ensure safe operations,” warned Patricia Sanders, chair of the agency’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel, at an April 25 meeting of the safety group. “I cannot emphasize more strongly that we advise NASA to retain this test.”

Gerstenmaier, at last week’s board meeting, indicated that NASA hadn’t decided yet about the test despite reports the agency had chosen to retain it. “We’re looking at potentially either deferring the green run or expediting the green run to look and see if we can save some time,” he said. He noted that a brief static fire at KSC wouldn’t test everything that they’d like to see in the core stage that would be accomplished with a green run test at Stennis.

He said, though, that launching EM-1 in 2020—earlier schedules called for launching that uncrewed mission in the middle of 2020—was looking doubtful. “We’re probably looking, best-case, maybe a late 2020 launch, but probably more than likely some time in 2021 for Exploration Mission 1,” he said.

A delay in EM-1, though, would not necessarily affect EM-2, the first crewed SLS/Orion mission, he said, because much of the hardware for that mission is already being built. “It’ll be ready to fly some time in the ’22 timeframe,” he said.

“We’re starting to buy hardware for EM-3,” he added, “and in the current scenario EM-3 would be our lunar mission. That would be our 2024 mission.”

On EM-3, the crewed Orion spacecraft would go to the lunar Gateway. That Gateway, though, would be different from concepts discussed by NASA and its partners just two months ago, which involved a series of modules and other components from various countries in a near-rectilinear halo orbit around the moon, assembled over the course of several years.

| “I would say that for the initial 2024 landing, it’s going to be pretty Spartan,” Gerstenmaier said. |

For the 2024 lunar lander, NASA envisions a “minimal” Gateway. One element of the Gateway would be the Power and Propulsion Element (PPE), which generates power for the Gateway and provides electrical propulsion. NASA solicited proposals from industry last year for the PPE, seeking to leverage designs based on commercial satellite buses. NASA is currently reviewing those proposals, and Gerstenmaier said he expected an award to be made by this summer.

The second element of that minimal Gateway would be a docking node that would also serve as a small habitation module. Gerstenmaier said it would likely be based on concepts for habitation modules already under study by several companies as part of the Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) program. “There’s going to have to be some changes to put some docking ports on the outside,” he said of those concepts, but otherwise NASA can move ahead from current studies to hardware procurement. “By the end of this year, we can have the habitation portion needed for this Gateway piece on contract,” he said. “That should allow them to deliver some time in ’23.”

Those would be it for the minimal Gateway. “That is all that is needed to essentially support a lunar landing,” he said.

The biggest effort would go towards developing the lunar lander system. Since last fall, NASA has talked about a three-stage concept for those lunar landers: a transfer vehicle to move the lander from the Gateway to low lunar orbit, a descent stage to go to the surface, and an ascent stage to return directly to the Gateway.

NASA initially took a piecemeal approach for the lander development, back when it wasn’t contemplating a human landing until 2028. Early this year it released a call for proposals for studies of the transfer vehicle and descent stage as part of the NextSTEP program. At the time, NASA said it was keeping work on the ascent stage in-house because of its human-rating requirements. Those proposals were due to NASA March 25—a day before Pence announced the 2024 landing goal.

Less than a week later, NASA said it would issue a new call for proposals, again part of NextSTEP, for the ascent stage. But even before that call was released, NASA changed directions again, announcing April 26 that the upcoming procurement would cover the entire three-stage landing system rather than just the ascent module.

“Now we’re asking for a service of ascent, descent, and transfer; essentially, an all-in-one service for landing,” Gerstenmaier said. “You can almost think of it as commercial landed services.”

He said this revised approach gives accountability, and design flexibility, to a single company. “They could make those trades,” he said. “Maybe it doesn’t have to be three pieces. Depending on where you put the propellant, where you put the tankage, you might be able to do it with two, two and a half [pieces]. There might be some other clever concepts there.”

Once on the Moon, though, the astronauts would be pretty limited in what they would do. Asked about the development of spacesuits, Gerstenmaier suggested there would be full-fledged next-generation suits ready in time for a 2024 landing. “I would say that for the initial 2024 landing, it’s going to be pretty Spartan,” he said. “There won’t be much there. We’re looking what the minimum is we need for suits to go out and do things. We’re going to keep that as small and as lean as we can.”

Those suits, he said, would be based on existing components. “It’s not very pretty. It’s not very conducive to very extensive operations on the moon, but I think this is a tradeoff that we’re giving to get there early.”

That landing would be limited in general. “There will not be a ton of time on the surface on this first flight,” he said. “You’re going to see a pretty minimalist kind of mission for that 2024 mission because of the constraints.”

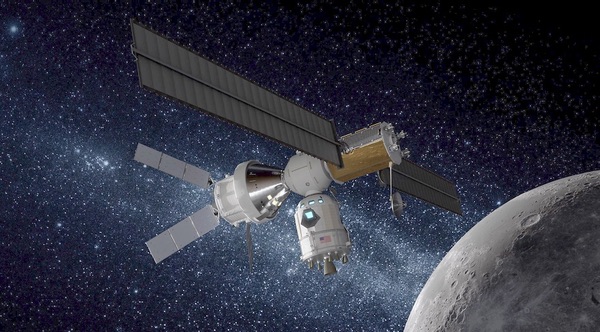

A Lockheed Martin concept for a minimal lunar Gateway with both an Orion spacecraft and lunar lander docked to it. (credit: Lockheed Martin) |

How, but not how much

While Gerstenmaier laid out how NASA could achieve a 2024 lunar landing, neither he nor others at NASA have said how much it will cost, beyond stating that they will need additional funding beyond what was previously projected to achieve that goal.

“You’re going to see a lot of budget move into 2020 and 2021 and 2022,” he said. “We’re spending an inordinate amount of time building budgets, building plans, showing that we have a credible plan to get to 2024 that can justify pretty extraordinary measures: some kind of budget amendment, some kind of emergency funding. We don’t know exactly the mechanism we’ll get.”

| “I will tell you that is not accurate. It is nowhere close to that amount,” Bridenstine said of reports NASA was seeking an additional $8 billion a year, but wouldn’t give aa more accurate number. |

Bridenstine offered a similar strategy the next day at a hearing of a Senate appropriations committee on the agency’s original fiscal year 2020 budget proposal. “The only things that we need to do is take those elements that were going to be funded in those other years and move them forward,” he said. “Think of this as, in essence, a surge of funding for the purpose of getting to the Moon within the next five years.”

What he didn’t say, though, is how big that surge would be, to the frustration of senators. “Someone in the administration is going to be requesting additional dollars,” said Sen. Jerry Moran (R-KS), chairman of the commerce, justice, and science subcommittee. “Do we know what the amount of those additional dollars will be?”

Bridenstine wouldn’t give an amount, saying it was still being worked out among the agency and White House organizations like the Office of Management and Budget. “We at NASA have put together, I think, a pretty good proposal to OMB and to the National Space Council. They are doing their own independent assessments to basically come up with a unified administration position.”

There had been rumors just prior to that hearing that claimed that NASA wanted an additional $8 billion a year for five years. “I will tell you that is not accurate. It is nowhere close to that amount,” he said, but wouldn’t give a number. “I don’t want to throw out a number until we have gone through the process with the OMB and the National Space Council.”

Many open questions

While the focus in the last six weeks has been on how to get astronauts on the Moon in 2024, Bridenstine has emphasized that the agency is still committed to a long-term presence there. In a speech last month at the 35th Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colorado, he said the agency now had a two-phase approach to its lunar exploration plans.

“The first phase is speed. We want to get those boots on the moon as soon as possible,” he said. “Anything that is a distraction from making that happen we’re getting rid of.”

The second phase, starting after that 2024 landing, would shift to sustainability. “We’re building a capability, we’re building an architecture that’s ultimately sustainable for the long run,” he said. “All this was already planned for 2028. We’re just going to accelerate pieces of it.”

| To complete a lander in time for a 2024 mission “we need to be bending metal next year,” said Lockheed’s Chambers. |

Scott Pace, executive secretary of the National Space Council, offered a similar argument of a “strategy of speed leading towards sustainability” in a speech April 23 at an event in Washington marking the 50th anniversary of the Universities Space Research Association. He envisioned the Gateway evolving into a propellant depot of sorts, enabling reusable lunar landers and other spacecraft. “Instead of abandoning expensive vehicles after a single trip, we should contemplate creating a fuel depot to enable repeated visits to the moon and pave the way to Mars,” he said.

He also supported development of a lunar base at the south pole, which could serve as a field station enabling exploration of the rest of the Moon while also taking advantage of potential water ice resources there. “A lunar south pole station can be an access point to the rest of the lunar surface,” he said.

But even as officials promote that long-term vision, other suggest that many near-term elements are still up for debate. While NASA talks about using a minimal Gateway for that 2024 lunar landing, a White House official said that may not be necessary.

“Some people were wondering if the Gateway was still in the plans. Well, it may not be in the initial critical path to getting to the first landing in 2024,” said Ryan Whitley, director of civil space policy at the National Space Council, during a presentation at the National Academies board meeting a few hours before Gerstenmaier spoke. He added that a Gateway was still seen as “part of the sustainable solution” for missions after 2024.

Asked about that by board members, he backtracked somewhat. “We believe that a minimal Gateway is part of the 2024 solution,” he said. There were alternative scenarios, though, he suggested, that might involve the Orion spacecraft docking with the lunar module directly in lunar orbit, rather than using a Gateway. “It’s just a matter of how that ends up playing out in the design of the systems.”

And, while Pence specifically said in his March speech that the landing would take place at the south pole of the Moon, that, too, could be up for reconsideration. “If it turns out to be part of the way to get to 2024, it’s possible we’d go back to the equator instead,” said James Reuter, NASA associate administrator for space technology, during a presentation at a meeting Tuesday of the technology committee of the NASA Advisory Council. For now, though, “the south pole is the target.”

While the details of the architecture and its cost remain in flux, NASA, the White House, and Congress will need to make decisions soon. At Space Symposium, Lockheed Martin offered its vision of a way to get to the lunar surface by 2024, one that looks similar to what NASA is contemplating: using EM-3 to launch the astronauts who would land on the Moon, and making use of a minimal Gateway. The company envisioned a two-stage lunar lander, and using the EM-2 mission to visit that Gateway and check it out prior to the landing, rather than do a free-return flight around the Moon as NASA currently contemplates.

Developing that lander is the pacing item in the schedule, company officials said. “We need to be bending metal next year, which means tooling already has to be in house, and I hope somebody ordered a bunch of aluminum,” said Rob Chambers, director of human spaceflight strategy and business development at Lockheed Martin.

“Right now I’m in the process of building a compelling presentation that lays out enough details” for Congress to be convinced it’s feasible, Gerstenmaier said. “We’ll know in the next couple of weeks whether we’re successful or not.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.