Inside the mind of the visionary who pioneered wireless power transmissionby Paul Jaffe

|

| Anyone that pigeonholes engineers as staid, emotionless creatures of logic will see this stereotype obliterated in light of Brown’s outpouring of vulnerability, colorful anecdotes, timeless wisdom, and philosophical musings. |

As a record of its time, the account proves a forceful, unfiltered primary source. Female engineers, save one, are completely absent in Brown’s account, as are female executives and female high-ranking government officials. Auto accidents are frequently fatal or life-altering. Disease takes lives quickly. Energy insecurity for society and financial insecurity for the “successful” are prevalent features. The impact of television already exerts its influence where “the artificial and the imagined have become the reality.” Proponents of space solar power will see the original sounds and echoes of today’s objections: it’s too expensive; it’s an energy project, not a space project; it’s a space project, not an energy project; there needs to be an incremental development path; and so on.

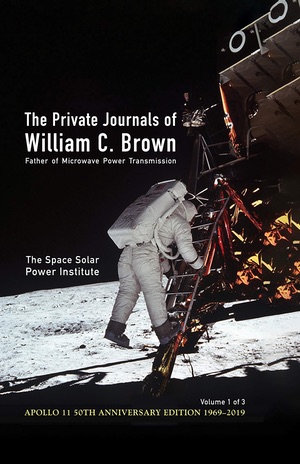

Brown’s genius and prescience are manifested in numerous ways. He writes about many ideas that have been subsequently rediscovered or that have blossomed in the intervening years, including the use of high frequencies for power beaming, space-to-space power beaming, laser power beaming, wirelessly powering drones and high-altitude craft, beamed energy propulsion, radiofrequency identification (RFID), electric cars, and a host of others. His enormous patent portfolio speaks for itself, and the image from the Apollo lunar landing on the book’s cover and in his account from July 1969 remind us that the world saw this historic event live, courtesy of his invention of the Amplitron transmitter.

The presentation of Brown’s journal is enhanced by front matter from his colleague John Osepchuk, his daughter Donna Salisbury, and Space Solar Power Institute Executive Director Darel Preble. The book is further augmented through the inclusion of historic photographs, images of handwritten diagrams captured from the journal itself, and a marvelous contribution from Richard Dickinson that fleshes out the story behind the historic power beaming demonstration that occurred at the NASA Goldstone Deep Space Network tracking facility, in which 34 kilowatts of power was sent a mile with a receiver conversion efficiency exceeding 82 percent.

By turns riveting, intimate, and suspenseful, Brown’s journal is perhaps even more relevant today than when it was originally written. Brown provides a personal window into the realities and tremendous challenges faced by those seeking to break ground with novel technologies, particularly those that cannot easily lay claim to quick returns on venture capital. Brown’s insights into the larger forces and considerations behind technologies and their adoption or abandonment are lucid and show keen sensibility. He paints a high-resolution picture of the pitfalls and travails to be overcome, all adroitly stitched together with glimpses into Brown’s individual, family, and community values.

Contemporary readers may be surprised to learn that even before email, social media, and the shredding of the modern attention span, there still wasn’t time to do it all or to achieve a satisfying work-life balance. Brown frequently characterizes himself as feeling hopelessly behind, overwhelmed, and “submerged,” despite what appear to be robust campaigns of personal fitness and objective accounts featuring surprisingly large amounts of skiing, hiking, yard work, church engagement, and social activities.

| The grand vision of space solar has yet to be realized. As Steve Fetter wrote in 2004, is it “an idea whose time will never come?” Or, is it merely a decade or two around the corner? |

Brown’s naked frankness is the root of his ability to produce spellbinding prose. He elucidates the bleakness and euphoria of frustration and success and delves into why when circumstances would seem to call for feelings of triumph, one may still feel pessimism or ennui. Brown’s insatiable curiosity and determination in enrolling in advanced coursework even while seeking to become an instructor himself belie a certain humble relationship with knowledge. Brown’s account shows a mind in near constant ardor, whether in his lab at Raytheon, in his home workshop, or sleepless in the wee hours of the morning.

What are we to make of Brown’s work, 50 years on? While we are starting to slowly see the possible inroads of power beaming into consumer electronics (see Ossia, Energous, PowerCast, Wi-Charge, and others), the grand vision of space solar has yet to be realized. As Steve Fetter wrote in 2004, is it “an idea whose time will never come?” Or is it merely a decade or two around the corner, as Chinese government investments announced earlier this year seem to suggest? Though this question has yet to be settled, no matter how it is resolved there can be no doubt that William Brown’s journal abundantly shows that he was instrumental in spearheading the foundations of the requisite technology of wireless power transmission.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.