Intersections in real time: the decision to build the KH-11 KENNEN reconnaissance satellite (part 2)by Dwayne A. Day

|

| Whereas the NRO position was that more R&D on electro-optical imaging was necessary, the CIA’s position was that it was essential to start a readout system by January 1970 and substantial funds should be committed to system definition work immediately. |

Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard was now chairman of the NRO’s Executive Committee. He advised Presidential Science Advisor Lee A. DuBridge, Director of the NRO McLucas, and Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms that the NRO’s next ExCom meeting should devote attention to the issues raised by Land’s memo.[4] Packard proposed that Herbert Bennington of the Department of Defense Research and Engineering lead a study that would report to the ExCom on four issues: the value of near-real-time-readout for indication-warning, crisis, and day-to-day intelligence activities; the relative merits of alternative approaches (in terms of area coverage, resolution, and frequency of coverage); the status of technology and its effect on the prospects of various alternatives; and the value and cost of alternative readout systems and their effects on the mix of other reconnaissance systems.[5]

A few weeks later, Colonel Lew Allen, then the Director of the NRO Staff, advised McLucas that Helms had decided upon more research and development for readout rather than moving quickly toward full-scale development. This was a more conservative approach than Din Land was advocating.[6] The NRO Staff supported the Director of the NRO in Washington, and the NRO Staff Director was usually a stepping stone for a military officer to then run SAFSP, the Air Force component of the NRO known as Program A and located in Los Angeles. SAFSP at that time was pushing for development of the Film Read Out GAMBIT, or FROG, satellite.

By 1969, another near-real-time-readout system had also emerged as a contender, primarily for crisis reconnaissance. Retired Major General W.A. Tidwell had proposed a crisis reconnaissance system after discussing the issue with Ray Cline, head of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research.[7] The name of this system is still classified, as are most details about it. NRO historian Perry stated that it evolved from earlier unfunded studies and would have been a film-return system that would have been recovered in the Atlantic Ocean, unlike the conventional film-return systems that brought their film down over the Pacific.[8] The murky description implies that this may have been a derivative of the ISINGLASS/RHEINBERRY system that was studied in the mid-1960s before being canceled, only to be briefly revived in 1968. ISINGLASS would have been a manned, air-launched hypersonic vehicle that would have been carried under the wing of a B-52 bomber. Launched far from the Soviet coast, it could have arced high into space, taken photographs, and then reentered the atmosphere. (See “A bat outta Hell: the ISINGLASS Mach 22 follow-on to OXCART,” The Space Review, April 12, 2010.)

But ISINGLASS would have landed at an airfield, whereas the system Perry mentions would have been recovered in the Atlantic Ocean, implying an unmanned vehicle. There were many limitations to this approach, including that it would not have stayed in orbit very long, if at all.

The August 7, 1969 ExCom meeting was dominated by issues generated by the Strategic Arms Limitations Talk negotiations. Although the United States had proposed to verify the treaty with satellite reconnaissance, “the quality and quantity of required coverage had not yet been specified.” The key issue was whether continual or periodic coverage at high resolution was required.[9]

By August 15, the NRO had developed a firm position, sponsoring a two-year technology advance program for ZAMAN and avoiding the selection of a system until the technology uncertainties had been resolved. John Foster, Director of Defense Research and Engineering, believed that high-resolution reconnaissance was a more important requirement than readout, but thought that either a modified GAMBIT or the HEXADOR approach would be suitable for the very-high-resolution mission. HEXADOR would have used DORIAN optics and a HEXAGON satellite vehicle and reentry systems.[10]

Whereas the NRO position was that more R&D on electro-optical imaging was necessary, the CIA’s position was that it was essential to start a readout system by January 1970 and substantial funds should be committed to system definition work immediately. Richard Helms declared that real-time-readout was an urgent national requirement.[11]

David Packard, who chaired the ExCom, ruled in favor of a more rapid technology analysis program than McLucas had advocated, a start on system development work, and establishment of a special task force to report to the ExCom on the status of the different technologies.[12]

| Land continued to push the ZAMAN program. In his view, “the electro-optical design is of such consummate simplicity, is so free from moving members, that there seems to be no point in waiting for an examination.” |

As NRO historian Perry observed, there were major industrial base considerations at stake. With MOL/DORIAN canceled, Eastman Kodak’s expertise in high-resolution reconnaissance systems was in jeopardy. Some of its workforce could be turned toward readout technology. But Eastman Kodak had primarily worked on Air Force NRO projects like GAMBIT and DORIAN, and the CIA’s favored contractors had been Perkin-Elmer and before them, Itek.[13] Thus, a selection of a specific system not only meant that contractors could be hurt financially, but also that the CIA or Air Force offices that primarily dealt with those contractors would have less work to do. In government, importance is determined by budget size, and winning the near-real-time project meant a lot to the Air Force people in Program A and the CIA people in Program B.

Land continued to push the ZAMAN program. In his view, “the electro-optical design is of such consummate simplicity, is so free from moving members, that there seems to be no point in waiting for an examination.” Land explained what he meant: “A mirror fixed at one end of a cylinder, with the cylinder pointing only towards earth, the image on a rigid solid, compact array, fixed in the focal plane—these add together to a breathtaking simplicity, solidity, and reliability” when compared to systems that included mechanisms for heat stabilization, film transport, mirror vibration, corona discharge, and “hundreds of similar incidental yet vital problems.”[14]

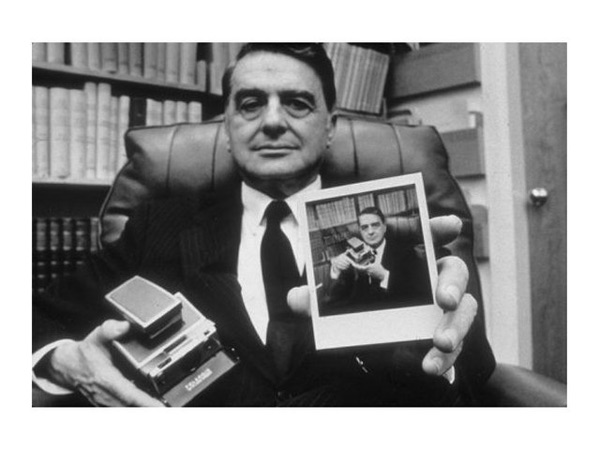

Edwin “Din” Land with his Polaroid SX-70 camera. Land was a senior intelligence advisor to the government as well as CEO of Polaroid. In 1970 Land was working on the troubled development of this folding instant camera at the same time that he was advising the US government to build what he considered a ”simple” near-real-time reconnaissance system then known as ZAMAN, later renamed KENNEN. |

At the time, Land was intimately involved in the development of the Polaroid SX-70 camera for the consumer market. Like previous Polaroid cameras it would produce near-instant print photographs. But the SX-70 was designed to fold up, to collapse to a flat package that was easier to store; it wouldn’t fit in your pocket, but it would slide into a shoulder bag. Doing so required numerous clever tricks, and was proving to be a difficult development. Land may have been impressed with ZAMAN’s simple optical path in part because he was personally dealing with something that had many moving and movable parts.

Other experts had a different view about ZAMAN’s apparent simplicity. They thought that the technology presented many inherent challenges including very large optics, a large and complex ground station component, very-high-bandwidth data relay equipment, and a difficult requirement for integration. The new system would require transmitters, antennas, and specialized components that were “beyond the state-of-the-art.” Others noted that large optics had proven troublesome in the past, and the optical system for ZAMAN would be larger even than the big mirrors manufactured for the now-canceled DORIAN.[15] Although it has not been declassified, one of the key aspects of the system was for the ZAMAN satellite to relay its imagery to a communications satellite at a frequency that did not penetrate Earth’s atmosphere and therefore could not be intercepted on the ground. The relay satellite would then transmit the imagery down at a different frequency. An artist illustration of a relay satellite for Samos was produced around 1960, but no information is available about this early concept and it does not appear that relay for satellite imaging was seriously considered until the latter 1960s. It was still an untried technology.

During the winter of 1969–1970, electro-optical imaging technology development made progress that reaffirmed the Land Panel’s endorsement of it. In March 1970, Land reported that a large mirror “with acceptable surface distortion had been fabricated” and it seemed reasonable that a larger, although slightly less precise, mirror could be fabricated for space use. Land estimated that the electro-optical imaging system could provide nominal two-foot (0.6-meter) resolution from 220-mile (407-kilometer) altitudes and the bigger mirror could provide the same resolution at 283-mile (524-kilometer) orbits.[16]

Land believed that a 1974–1975 operational date was entirely feasible “if we get on with the development.” Land still had a dim view of the FROG laser-scan system and believed that it was too complex and had limited growth potential.[17] The Land Panel also suggested that the ZAMAN system could take over the GAMBIT film-return mission if it operated lower, in 200- and even 100-nautical-mile (370- and 185-kilometer) orbits, although this would have required the satellite to be equipped with orbit adjust capability.[18]

Nixon’s newly created Office of Management and Budget was also involved in the deliberations and they were more skeptical of the near-term feasibility of ZAMAN. James Schlesinger was then at OMB and represented the office at ExCom meetings.[19] He was averse to high-risk technology and early cost estimates for complex systems, and presumably passed on his advice, and his skepticism, to OMB Director Charles Schultze, who expressed his own skepticism to Packard.[20]

In July 1970, the Land Panel and McLucas delivered reports to the NRO’s ExCom. McLucas’ report was less skeptical of electro-optical imaging than the OMB report. McLucas had based his conclusions on the technical success of the solid state array and its subsystems, as well as United States Intelligence Board guidance that such a system was “urgently needed.” McLucas advocated proceeding with system definition studies, which should be concluded in about twelve months leading to a system development decision for ZAMAN by November 1971.[21]

McLucas reasoned that the new readout system would replace GAMBIT and possibly even HEXAGON. He also speculated that if the ongoing tape storage camera development work was successful, it could be applied to GAMBIT to replace the laser-scan system. He recommended supporting development of a tape storage camera, and also purchasing both FROG and HEXAGON, apparently as a backup in case ZAMAN did not prove viable.[22]

McLucas noted that although ZAMAN was the “preferred approach” to a next-generation system, it was possible that in the future it could become too expensive to operate. SAFSP had concluded that FROG could be developed and built for about a third of the ZAMAN development cost.[23] Thus, McLucas was proposing that FROG might be useful as a backup to be pursued if ZAMAN proved too expensive.

John McLucas was Director of the National Reconnaissance Office during the decision to develop a near-real-time reconnaissance satellite. He favored the Film Read Out GAMBIT satellite over the ZAMAN electro-optical imaging satellite. (credit: US Air Force) |

Presidential Science Adviser Lee DuBridge and Director of Central Intelligence Helms initially decided that “early 1975” should be the target for the first launch of a readout system. On July 27, McLucas authorized the director of the CIA reconnaissance program to proceed with the system definition phase of ZAMAN beginning on August 1, 1970.”[24]

| One aspect of the “near-real-time” reconnaissance system that had been debated repeatedly was just how fast the images had to be returned. Did a spacecraft need to return the imagery for interpretation in mere hours, or could it take several days? |

By late 1970 it was becoming clear that other issues besides the satellite and its technology would have a major impact on the availability of the system. The data relay satellite program had run into problems. Its costs had risen, and it was difficult to identify and recruit other military users of the relay satellites, something that was necessary for both political support and the satellite cover story.[25]

Another problem involved interpreting all the imagery that the satellites would produce. The NRO already planned to collect a great deal more imagery in 1971 than ever before using GAMBIT and the few remaining CORONA film-return satellites. But by December 1970, Helms cautioned that there would not be enough interpretation capability to deal with HEXAGON, then scheduled to begin operations in the summer. Adding ZAMAN, which would be continuously producing imagery, was only going to increase the burden on photo-interpreters.[26]

By mid-1970, the ZAMAN program developers had started looking at “high-risk” and “low-risk” approaches to data handling. The lower-risk approach used existing equipment, but would result in slower data transmission and lower ground resolution. Din Land considered this to be unacceptable.[27]

Eugene Fubini had served as a reconnaissance adviser to Packard, but in October 1970 he independently objected to ZAMAN. Fubini felt that the CIA approach to ZAMAN had been to maximize what was technically possible rather than determine an optimum tradeoff between national needs and cost. He disagreed with a requirement that imagery reach the Washington intelligence community within an hour of ZAMAN’s passage over a target. He also did not think that the primary data reception facilities needed to be near Washington, DC. Furthermore, he thought that the field of view for the satellite was too narrow and had been dictated by strategic requirements. “If strategic reconnaissance were the only basis for a readout system, I would strongly urge that the program be canceled,” Fubini wrote Packard.[28]

Fubini also had a different take on the issue of collecting too much imagery for the photo-interpreters to look at. He pointed out that it was already difficult to specify 50,000 reconnaissance targets of valid interest, but that by 1972 the NRO planned to try to photograph 160,000 targets, likely resulting in 100,000 of them being imaged. The goals that were driving ZAMAN were mismatched to what Fubini believed needed to be done and instead of going after so many targets, reconnaissance satellites needed to concentrate on the more important ones. ZAMAN needed to focus on national frontiers, aircraft deployment patterns, the movement of naval forces, and other similar tasks to provide warning of imminent military action, but its field of view was too narrow to be useful for these goals. Fubini recommended widening the field of view, adding storage capability onboard the satellite, providing for readout directly over the United States rather than via relay satellite, and accepting a greater delay in the delivery of imagery.[29] According to Perry, some of Fubini’s recommendations, like onboard storage, were not technically feasible even four years later.

One aspect of the “near-real-time” reconnaissance system that had been debated repeatedly was just how fast the images had to be returned. Did a spacecraft need to return the imagery for interpretation in mere hours, or could it take several days? Raymond Cline, who was the director of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research, told COMIREX in January 1971 that in his opinion a one- to three-day wait for reconnaissance imagery was acceptable. He also believed that two- to four-foot (0.6- to 1.2-meter) ground resolution would be fine. He advocated for a “Model T” satellite system to produce photography that could be declassified and shared openly with other members of the United Nations. Cline thought that a system that could be developed in 18 months using off-the-shelf technology would be very useful.[30] The ability to use reconnaissance satellites for international diplomacy was something that had concerned officials in the State Department. State had earlier objected to the impending demise of the CORONA program and had tried to revive CORONA in 1970.[31] Now officials at the State Department were trying to influence the debate over real-time reconnaissance.

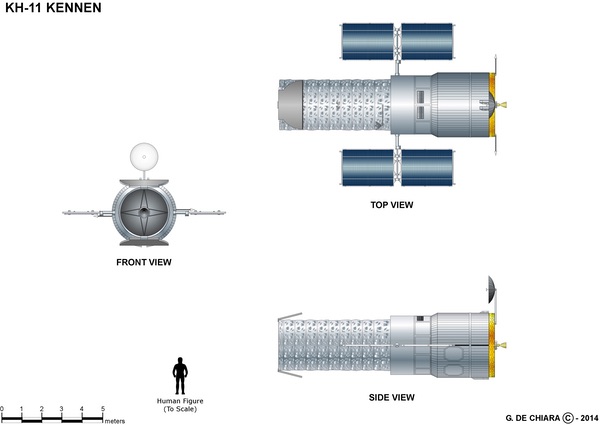

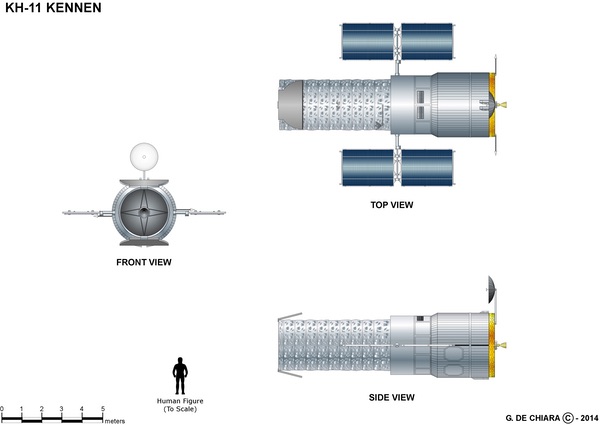

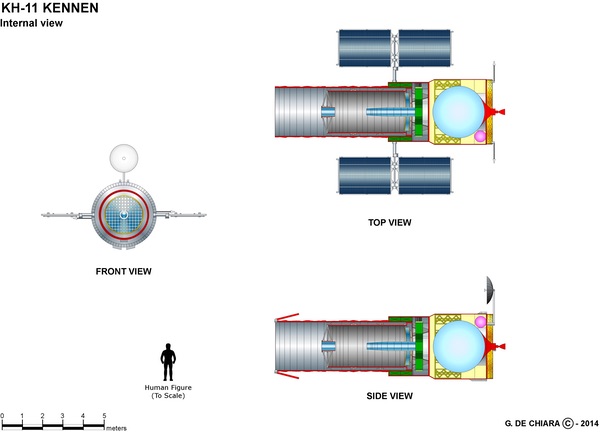

Artist impression of the KH-11 KENNEN satellite. The satellite had the same diameter primary mirror as the Hubble Space Telescope. But unlike Hubble, it did not need a large compartment for multiple instruments, but did need fuel for periodic orbit reboosting. (credit: Giuseppe de Chiara)  |

The debate heats up

By January 1971 another meeting of the NRO’s Executive Committee was planned, and thus there was renewed discussion and lobbying for the selection of a near-real-time reconnaissance system. ZAMAN and FROG were the obvious competitors, but other options were still under discussion.

On January 8, 1971, COMIREX chairman Roland Inlow and his Crisis Analysis Task Group traveled to the State Department to meet with Ray Cline. They discussed timeliness, resolution, State Department imagery requirements, as well as advanced vs. less-innovative reconnaissance systems. According to a memo to NRO director McLucas, Cline believed that “a two-to-six hour response capability is not really necessary.” With good repetitive coverage, a one-to-three-day gap would be acceptable. Cline suggested that a simpler system that could deliver imagery in that period might eventually “be a useful complement” to ZAMAN.[32]

Secretary of State William P. Rogers urged Helms and Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird to support development of Cline’s proposal. “As Ray Cline puts it, we need a ‘Model T’ or ‘Volkswagon’ to get us to the brushfire on time when our more expensive and less maneuverable Cadillacs are not able to cover that particular crisis on that particular day or week.”[33]

| McLucas also noted that there was concern that if FROG was successful while ZAMAN was still well short of completion, “our friends in Congress might challenge whether we ought to finish the development.” |

ZAMAN had completed initial system definition phases in December 1970 and moved into its second phase of system definition intended to lead to firm design and cost estimates in February 1971. The system was supposed to operate in a near-polar elliptical orbit, with a perigee of 188 nautical miles (348 kilometers) with an apogee between 283 and 424 nautical miles (524 to 785 kilometers). The plan was for the system to become operationally available in April to June 1975.[34]

FROG would generate 400 frames of imagery a day. It could use a relay satellite, but unlike ZAMAN it did not require one. It could achieve two-foot (0.61 meter) ground resolution from an orbit of 170 nautical miles (315 kilometers). Film capacity would limit FROG to a two-year operational life. It would require a three-year development program.[35]

One of the issues driving McLucas’s skepticism about ZAMAN was that big, complex intelligence satellites had cost far more than their initial estimates. McLucas noted that both HEXAGON and another system that was probably the RHYOLITE signals intelligence satellite had eventually cost more than twice their initial estimates.[36]

Also in January 1971, McLucas received a letter from Carl Duckett, the CIA’s Deputy Director of Science and Technology and the CIA director for reconnaissance programs, which noted that there were several candidates for crisis reconnaissance systems and it was clear “that within the next six months the Executive Committee must decide whether it wants to invest a significant amount of money in the more limited capability systems for this specific requirement and, if so, how this investment should impact the plans for an EOI (electro-optical imaging) system.” Duckett recommended creating an ad hoc committee to establish performance criteria, which would be reviewed by a panel headed by Din Land. In the meantime, Duckett suggested that “we discourage any efforts to compare alternative systems.”[37]

The ExCom met on January 29 and approved continued funding for both ZAMAN and FROG at their on-going rates. They also rejected the State Department’s “Model T” approach. The committee expected that a final decision could wait until November 1971—later than the six-month period Duckett noted in his letter.

In a paper from McLucas to Deputy Secretary of Defense David Packard, the NRO director noted that there were many consequences to the decision to fund two programs as opposed to only one. First was that funding for the two systems would consume “roughly one-third of the NRO budget for the foreseeable future” and produce a 20 percent increase in the NRO’s budget “during a time when the intelligence community overall is being asked to cut back.” McLucas also noted that the course selected by the committee was “not universally acclaimed,” which was apparently his diplomatic way of saying that the CIA was opposed.[38]

McLucas then reported that he had discussed the decision with Director of Central Intelligence Richard Helms, presidential science advisor Eugene David, Director of Defense Research and Engineering John Foster, DoD official Robert Froehlke (who would become responsible for DoD intelligence resources in June), Secretary of the Air Force Robert Seamans, and assistant OMB director James Schlesinger. “With the exception of Dick Helms, these men almost universally think that a different course would be better and are in surprising agreement as to what we should do instead.” They were concerned that requesting funding for ZAMAN would be “following too close on the heels” of the expensive HEXAGON search satellite, and would be “inviting trouble with Senator Ellender and others.” Senator Allen J. Ellender (D-La.) was chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, and he had become embroiled in the discussion over near-real-time reconnaissance.

McLucas also noted that there was concern that if FROG was successful while ZAMAN was still well short of completion, “our friends in Congress might challenge whether we ought to finish the development.” They considered a proposal to delay ZAMAN and redesign the system “to achieve something significantly different from what EOI will now do.” Possible modifications involved flying the satellite in different orbits, and combining the ability to search at lower resolution in near-real-time with the capability of detailed examination of selected targets.[39] McLucas believed that the only person at the meeting opposed to delaying ZAMAN was Richard Helms.

On April 22, 1971, a letter from George Shultz, director of the Office of Management and Budget, informed ExCom members that President Nixon wanted to have a near-real-time imaging capability at an early date.[40] NRO historian Perry noted that the available records did not indicate if Nixon was interested in this capability as a technology, or as a means of acquiring better intelligence.[41]

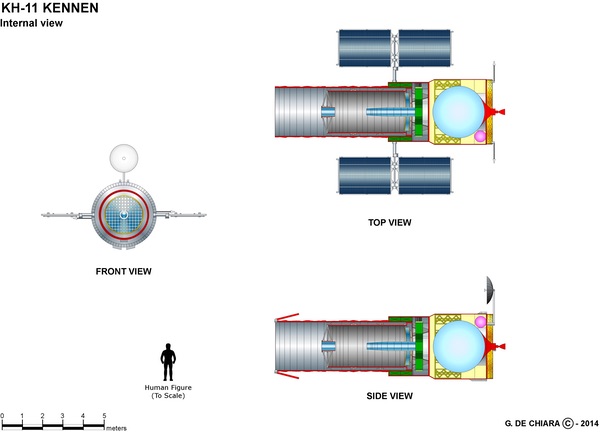

Artist impression of the KH-11 KENNEN satellite. The satellite had the same diameter primary mirror as the Hubble Space Telescope. But unlike Hubble, it did not need a large compartment for multiple instruments, but did need fuel for periodic orbit reboosting. (credit: Giuseppe de Chiara)  |

FROG gets approval

On April 23, ExCom met again. The ExCom minutes stated that “the President has expressed vigorously the desirability of near-real-time [NRT] and the President… wished to have this capability during his second term in office,” meaning by 1976 at the latest since a Nixon second term would end by January 1977.[42]

| A codeword was a serious issue, because it meant a separate security compartment with rules and procedures and the granting or denial of access to information about the program. In simple terms, it was about red tape, access, and money. |

At one point there had been up to 12 alternatives for obtaining crisis reconnaissance, but by April 1971 the list had been narrowed down to three options: proceeding directly to ZAMAN (while relying on GAMBIT and HEXAGON in the interim), adding FROG to the inventory, or a still classified third alternative instead of FROG, which may have been the suborbital reconnaissance option, with ZAMAN phasing into operation later.[43]

The ExCom decided to acquire FROG as “a crisis reconnaissance and interim system.” The NRO wanted firm bids for developing the system by July 1, with the expectation that the first flight would occur 30 months after signing the contract, in 1974.[44] If the NRO ExCom’s recommendation was followed, FROG would enter service in January 1974 and ZAMAN in calendar year 1976.[45]

Brigadier General Lew Allen, who had left his position at the NRO Staff and after being promoted, became head of SAFSP/Program A in Los Angeles, then defined the FROG program to McLucas, stating that on April 28 contracts were initiated with Lockheed and Eastman Kodak for the definition phase of the system. The system definition costs were based on a four- to six-vehicle buy. Eastman Kodak was assigned “responsibility for the entire imaging chain from entrance pupil to reproduced photograph on the ground.” Kodak selected Radiation Inc. as the subcontractor for the data link. The laser scanner subcontract had not been selected. “I fully intend to initiate, develop, and fly this interim readout system in 36 months after go-ahead, and to manage it with firm cost-conscientiousness, schedule, and performance considerations,” General Allen declared.[46]

Allen also noted that the government might want to share the imagery with other partners as part of arms control negotiations. “This product would not be specifically revealing of the capabilities of GAMBIT recovery, HEXAGON or ZAMAN,” Allen added.

One of the issues that NRO officials wrestled with was whether or not FROG should be given a codeword separate from GAMBIT. Although FROG did not have its own codeword, it did have a still-classified designator. A codeword was a serious issue, because it meant a separate security compartment with rules and procedures and the granting or denial of access to information about the program. In simple terms, it was about red tape, access, and money.

General Allen believed that an entirely separate codeword designation was unnecessary, reasoning that most of the people who required clearance to work on FROG would have to know about the GAMBIT spacecraft anyway—after all, it used the GAMBIT-3 camera system—and the single codeword would be good enough. There might be some cases where they would need to deal with security access for the ground system, presumably in order to keep people who had access to the read-out imagery on the ground from learning about the capabilities of the higher resolution film-return GAMBIT, but they could sort that out when the problems arose.[47]

A few days later, an NRO official whose identity has been deleted from an internal memo discussed the pros and cons of establishing a separate codeword for the FROG system, providing what he referred to as the “big picture.” Among the pros that he listed: “The system is a new collection system—that is, it represents a most significant enhancement of the U.S. collection capability.” One purpose of a separate codeword for the system would be to shield its identity from the Soviets, at least for a little while. But the writer also noted that there was a “tacit understanding” between the superpowers to not interfere with either country’s reconnaissance satellites. Would this unspoken agreement still hold up once the United States was operating a near-real-time reconnaissance system and could see what the Soviet Union was doing almost as soon as it happened? As the official noted, the Soviets currently had an expectation that it would take between 7 and 60 days before photos would be analyzed on the ground. FROG would cut that to possibly only a few hours. “Will they passively accept this new capability?” he asked. If not, they might attempt to attack the satellites. The official also acknowledged that once FROG was in orbit, it might not take the Soviets long to figure out its mission, and so a separate codeword might not make any difference at all.[48]

The new system would include some new companies and personnel. “Do we want the old players to know of the new capability, and the new players the olde [sic] capabilities? Can we effectively control need-to-know without a new codeword?”

As for the “cons,” he noted that FROG “is an extension of the GAMBIT system. In the past we have not normally changed the [security] controls for system growth.” In addition, most of the players in the new system are the same that had long worked on GAMBIT. Finally, when it came to documentation “there is a potential nightmare in the administration of determining where GAMBIT stops and FROG starts,” he wrote.

Even when FROG started flying the NRO would still launch regular GAMBIT-3 missions, because nothing could match the high-resolution photography that GAMBIT could produce. Major Robert A. Schow, who worked for the NRO, noted that numerous upgrades to GAMBIT had previously been proposed in isolation and rejected, but now that FROG had been approved, those improvements “may be realizable as an outfall of the FROG program.”[49] Presumably many of them involved increasing the lifetime of the spacecraft. At the time GAMBIT-3 missions only lasted a few weeks, whereas FROG would have a lifetime of up to two years.

Controversy and confusion

Din Land was unhappy with the ExCom’s April decision to develop FROG. He got a chance to register his disapproval during a June 4, 1971, meeting of the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB), whose members included Land, William Baker of Bell Labs, former national security advisor Gordon Gray, and former chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Maxwell Taylor. Usually Henry Kissinger and his deputy attended, representing the President. But this meeting also drew Nixon himself, along with Schlesinger, who was still at OMB but would soon move to take over the Atomic Energy Commission.

| Land didn’t seem to recognize any fundamental technical problems with the electro-optical system and “is not especially critical of the looseness of the requirements situation. To put it another way, if EOI is a technology-driven development Dr. Land is a main driver.” |

At the meeting, Land expressed his strong disapproval of the ExCom decision to endorse FROG as an interim system. Land argued that such a decision would delay or even defer ZAMAN development. Land told Nixon that bureaucrats are unwilling to assume large financial risks without “strong Presidential backing.” Land said that FROG would be “the cautious choice,” whereas the “adventurous choice, and one which would be a quantum technical advance, is to push the development of an electronic imaging system which can be read out through a relay satellite while the sensor is over the target.” Nixon promised to take a hard look at the issue.[51]

As NRO historian Perry noted, Land’s appeal to Nixon was masterful, because he both praised the president’s insight and portrayed McLucas’ preference for FROG not as bold and ambitious, but a typical conservative bureaucratic decision—which of course was exactly what it was.[52]

But also according to Perry, FROG was no longer as simple as it had once been. Its own managers believed that it was essentially a new program that only shared some hardware with GAMBIT-3. Its operational capability had grown considerably since the system was invented. According to a principal FROG designer, “there are many more characteristics of this system, its mission, hardware and operation that are dissimilar to GAMBIT-3 than similar.” Only the Kodak optics module survived. Many of the Lockheed spacecraft subsystems would be modified, and the software and satellite control facility operations were totally new. “The operational philosophy is nearly all new. Many of the key development areas bring totally new fields of technology to the current program.”[53] As Perry noted, this view was widely held within the program office, but was not the view held by ExCom or Packard. Packard even sent a letter to Senator Ellender stating that developing FROG was “system integration rather than system development,” and added that “I am convinced we will eventually need the added capability and speed of response which the EOI system can provide—but that we cannot wait until 1976 for this system.”[54]

On June 11, the Land Panel met to discuss the two systems. The panel’s discussions were summarized in a memo by the head of the NRO’s Washington, DC staff, Colonel David Bradburn, who had taken over from Lew Allen.[55] The first issue that the panel heard about was a recent COMIREX study of crisis scenarios. Roland Inlow described seven crisis situations and defined both the size and shape of the area in each of them that would have to be imaged to provide actionable intelligence. There was a lot of variation on the points, but they tended to boil down to an average of 4,000 square nautical miles (7,400 kilometers) and one to five feet (0.3 to 1.5 meters) resolution. What Inlow did not discuss was the timeliness issue, specifically “how the faster availability of photographs would have improved our response during the crisis.” Considering that the invasion of Czechoslovakia three years earlier had highlighted the timeliness issue, and the FROG system in particular had been advocated in terms of its ability to contribute to crisis intelligence, it is surprising that the value of timeliness of the imagery still had not been clearly articulated by anybody in the intelligence community by June 1971.

According to Bradburn, Air Force officers then briefed the Land Panel on the FROG system. Land was highly skeptical and asked a number of pointed questions. Land argued that the panel was not being given detailed technical briefings, but instead was given assurances by the contractors that everything was okay. In response, Brigadier General Allen arranged a follow-up meeting with several members of the panel to discuss some of Land’s specific areas of concern, primarily FROG’s bimat processing system and the laser scanner. On the latter issue Land was worried about bearing wear-out leading to failure of the system.

The panel was also briefed about the ZAMAN system and told that the plan was for a January 1976 launch, but that an accelerated schedule with a December 1974 first launch was possible with increased funding.

Colonel Bradburn finished his memo summarizing the meeting by stating that Land didn’t seem to recognize any fundamental technical problems with the electro-optical system and “is not especially critical of the looseness of the requirements situation. To put it another way, if EOI is a technology-driven development Dr. Land is a main driver.”

The Land Panel reported to President Nixon that FROG was “substantially inferior” to ZAMAN, and FROG was also a higher risk because more new subsystems and components had to be developed and operated in FROG than ZAMAN. Land had argued that ZAMAN could be developed for a first flight by late 1974, and FROG would be more expensive than stated. He claimed that this would only result in an inferior product one year sooner with probable delay of the superior capability.[56]

Although Richard Helms had earlier supported FROG as an interim system until ZAMAN became operational, by June 1971 he had backed away from that opinion and proposed buying a few more GAMBIT vehicles instead of FROG and keeping them on standby for crisis use. Helms believed that FROG had changed in scope and “the FROG proposal as currently perceived is structured as a competitor to EOI and, therefore, is not necessarily the only or best hardware approach to an interim-system.”[57]

Also in June, McLucas suggested that ZAMAN should be delayed and redesigned to “do something FROG won’t.” He also suggested that HEXAGON should be canceled once ZAMAN became operational—implying that ZAMAN should take over the search role. According to Perry’s official history, McLucas was essentially proposing that FROG be the primary crisis response system of the 1970s and 1980s.[58]

Up until this time, the consensus opinion—with the notable exception of Din Land—was that FROG should be pursued as a near-term, interim system until ZAMAN became available. But by June 1971, the two sides in the discussion had become further polarized: CIA wanted ZAMAN and opposed FROG out of a belief that if FROG was developed, it would delay or eventually cancel ZAMAN. The NRO’s position, as espoused by McLucas, was that FROG should be pursued and that ZAMAN should be delayed and possibly redefined. McLucas’ proposal to eliminate HEXAGON—a CIA-developed system on the cusp of becoming operational—may have been based upon a belief that HEXAGON would no longer be needed, but could also have been further bureaucratic maneuvering to oppose a major CIA project.

The two alternatives were discussed again at the end of June at a National Security Council meeting attended by President Nixon where the success of the first HEXAGON mission, launched on June 15, was also noted. When the subject of the proposed electro-optical system came up Nixon commented that “Land says it can be done and we all know what a genius he is and what he has accomplished… The resolution is also supposed to be better than anything we have now. Land spoke with such conviction that I would like to hear your views about whether or not we should go forward, especially because of the connection with a SALT agreement.”[59]

Deputy Defense Secretary David Packard told Nixon that “the system is a good idea. It is based on new technology – solid state sensors. It has better characteristics than a camera, that is, it can take better pictures with less light. There are some problems but there is no question about feasibility.” He then discussed the cost estimates for the various options. Nixon responded by asking how long it would take to develop the system, and Packard told him it would take until 1976. Packard added that “the key issue is, do we want to have this capability sooner?” and then informed Nixon that there was an alternative – FROG – that could be available in 1974. Since ZAMAN would “not be available until at least 1976 at the earliest,” he asked “do we want to have something in the interim?” and added that FROG would cost only a third of the alternative system.[60]

Nixon’s conclusion was that “in the light of the negotiations in SALT and the need for verification, we probably need both” since if “we got a SALT agreement by… January 1972, we might not want to wait until 1976” for near-real-time reconnaissance. Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird and Deputy Secretary of Defense Packard told the president that both systems were funded in the fiscal 1972 budget and that the plan was to have the interim system (FROG) and then proceed to ZAMAN “when the bugs are all worked out.”[61]

| In a dispute that will be familiar to anyone knowledgeable about space program cost estimates, Carl Duckett defended the ZAMAN cost estimates and claimed that they were more reliable than estimates for HEXAGON had been when it was approved seven years earlier. |

But there was, according to Melvin Laird, a “pressing problem”: specifically, Senator Ellender, who wanted to cut $500 million out of the Intelligence Community’s budget. If the cut was sustained by the Senate, then “one of the systems might have to go.” Packard then suggested that “with such a cut we might have to cut out the proposed interim system and wait on the Land system which is better.” Ultimately, Nixon ended the discussion with the observation that “we should have another talk about this later.”[62]

According to Perry, Senator Ellender quickly made compromise impossible by introducing the budgetary concerns and politely indicating that the reconnaissance community could choose one of the two systems but not both.[63] Ellender’s position played to the CIA’s benefit, because the CIA only wanted ZAMAN, not FROG, whereas the existing policy was to pursue FROG first and ZAMAN eventually, a far more expensive plan.

The next ExCom meeting was held on July 15. ExCom had three options: anticipated first launch of ZAMAN by January 1976, delaying launch until June 1976 at a lower cost, and a June 1975 first launch at a higher cost. The first two options assumed developing FROG and launching it in 1974, but the third option deleted FROG entirely.[64]

In a dispute that will be familiar to anyone knowledgeable about space program cost estimates, Carl Duckett defended the ZAMAN cost estimates and claimed that they were more reliable than estimates for HEXAGON had been when it was approved seven years earlier. HEXAGON had eventually doubled in cost, but Duckett claimed that not enough was known about the HEXAGON technology when those estimates were made, whereas ZAMAN’s technology was well understood. But Perry noted in his history that Duckett was misstating the facts about the HEXAGON estimates, and that as early as September 1964, CIA officials had claimed that HEXAGON’s technology was also well understood and therefore their cost estimates were reliable. Clearly they had been wrong on both counts.[65]

Packard argued that a 1975 launch date for ZAMAN was unrealistic no matter how much funding was provided. He believed that 1976 was the earliest possible launch date and could only be maintained with a fair amount of luck. He believed that it was better to adopt a conservative schedule for ZAMAN.[66]

McLucas suggested that a solution was to finish R&D on FROG and only then start system development of ZAMAN, which would slip ZAMAN to 1978 but both resolve the budget issue and result in a readout system becoming available in 1974. Schlesinger endorsed the proposal and Packard also seemed inclined to do so.[67]

These discussions were intended to produce a joint memo from the ExCom members. On August 2, Helms proposed that the ExCom present five options to the president:

- ZAMAN on a 1976 schedule,

- ZAMAN “before” 1976,

- ZAMAN in 1976 and a “low cost interim system” earlier,

- FROG in 1974 and ZAMAN in 1976, and

- FROG in 1974 and ZAMAN in 1978.[68]

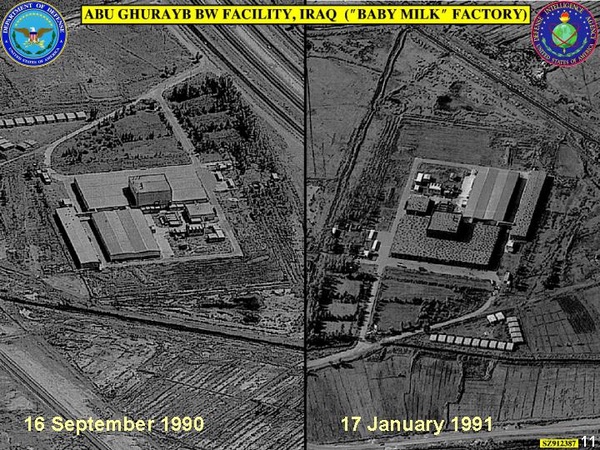

Declassified satellite image released during the 1991 Persian Gulf War. (credit: Department of Defense) |

Spooky actions at very short distance

After several weeks of effort, it became clear that ExCom was split. The 1965 NRO charter indicated that if ExCom could not come to agreement, the issue should be referred to Secretary of Defense Laird for resolution. Laird indicated that he would address Helms’ views before taking any further action.[69]

On August 9, Packard wrote a letter to Helms telling him to delay any action until Secretary of Defense Laird had time to review the issue. Helms then engaged in what appears to have been a very clever power play, the kind that one would expect from the head of an intelligence agency. Ignoring Packard’s request, or at best, unaware of it, Helms wrote a letter to President Nixon recommending that he order development of ZAMAN by December, with the goal of a June 1976 launch. He discussed FROG’s shortcomings and recommended relying on GAMBIT and HEXAGON in the interim. He identified the primary alternative not as developing FROG as an interim solution, but instead spending more money on ZAMAN to achieve operational launch by late 1974. Helms also stated that the choice was to pursue electro-optical imaging now or never, and stated that Eugene David, of DDR&E, and Packard favored never—which was not their actual position.[70]

| Perry referred to one unnamed observer who said that “there was little attempt at secret maneuvering on the part of the CIA…” since the CIA’s opposition to FROG and advocacy for ZAMAN had been blatantly clear all along. |

Helms’ letter was dated August 9, but a copy of Helms’ letter did not reach Laird until August 11. Presumably, if Helms had written the letter on August 9, a copy would have been sent to Laird on August 9 or 10 at the latest. Perry suggested that Helms actually wrote his letter to Nixon on August 11 and back-dated it to August 9, thus making it appear as if he wrote and sent his letter to the White House before he received Packard’s letter telling him to hold off on taking any action. At the very least, dating his letter August 9 provided Helms plausible deniability if Packard accused him of circumventing the process everybody had agreed upon for ExCom disputes—Helms could always claim that he wrote his letter to the president before seeing Laird’s request to delay.[71]

Perry referred to one unnamed observer who said that “there was little attempt at secret maneuvering on the part of the CIA…” since the CIA’s opposition to FROG and advocacy for ZAMAN had been blatantly clear all along. Perry also thought that no matter the technical merits of ZAMAN, the CIA had a clear institutional reason for supporting ZAMAN—now that development of HEXAGON was finished, the CIA’s satellite development office had no other projects on its plate and not only wanted, but needed ZAMAN if it was going to remain a player in the development of intelligence satellites.[72]

Helms’ letter also proved to be timely, because one of the key figures had shifted his position in the interim. As Helms’ letter went to the White House, presidential science adviser Eugene David had changed his mind. Whereas previously he had sought FROG as an interim system until ZAMAN became available, David now informed John McLucas at the NRO that electro-optical imaging should not be recommended as a feasible option and that Land was entirely wrong. David believed that FROG should be deployed and would provide experience useful for making better decisions about ZAMAN.[73]

Laird ultimately backed away from the earlier FROG decision and informed Nixon that the ExCom had decided to develop ZAMAN for a 1976 operational date, but at a different spending rate. He also stated that now that HEXAGON was available—the first successful HEXAGON mission had taken place in June 1971—it negated any need for early readout capability, and the best course was to proceed toward ZAMAN operation in 1976 “or possibly somewhat earlier.”[74]

Finally, in a September 23 Top Secret classified memo from Kissinger to Laird, Helms, OMB director George Shultz, Eugene David, and PFIAB chairman Admiral George Anderson, Kissinger informed them that Nixon had “decided that the development of the Electro-Optical Imaging (EOI) system should be undertaken under a realistic funding program with a view towards achieving an operational capability in 1976.” At the same time, he directed that all work on FROG should cease.[75]

Two weeks later it was noted at a meeting of COMIREX’s Exploitation Research and Development (EXRAND) subcommittee that the ZAMAN system was proceeding on schedule and that the official “Z” codeword had been “designated and accepted community-wide.”

But at a NRO staff meeting on November 23, NRO Deputy Director Robert Naka announced that he had selected a new codeword for the program: KENNEN. As a staff member noted, “the term is Middle English, and means ‘to perceive’”[76] It also received a designation for its camera system: “KH-11.”

Throughout the 1960s, codewords sometimes changed as systems went from study to full-scale development. FULCRUM, for instance, became HEXAGON. There was a good reason to change the name, as ZAMAN had been a research and development program whereas KENNEN was the development of an operational spacecraft. But as Perry noted, some NRO officials apparently considered the name change to be more evidence of CIA hubris, since Naka was “the CIA’s ‘man in the front office.’” In other words, by picking a new codeword, the CIA was marking its territory, and presumably could also control who had access to the new system, keeping out those who were cleared for ZAMAN that the CIA did not want involved.[77] Later, as the CIA started full development of KENNEN, it turned over continuing procurement of the HEXAGON camera contract to SAFSP, like handing down a used car—and the loan payments—to a younger brother. Managing an existing camera contract was a lot less interesting than developing an entirely new reconnaissance satellite.

A reconnaissance satellite image of Afghanistan taken in 2009 leaked by Edward Snowden and later published in the media. |

Conclusion

The debut of the KH-11 KENNEN in late 1976 followed five years of development. It was certainly a complex undertaking—not simply a new satellite, but multiple systems all having to work together. The NRO launched two Satellite Data System relay satellites starting in summer 1976. They also had to develop new ground processing equipment to take the electronic signals coming down from the relay satellites and convert them into imagery, as well as store them for later retrieval. According to sources, this early imagery was initially read out onto pieces of positive image film that analysts then looked at on light tables. There were efforts to develop TV displays for the imagery for analysts to look at, but apparently these did not work very well, and anybody familiar with trying to manipulate even small size images on computers in the 1980s and 1990s understands how slow computers were at handling them. Film remained a powerful and easy to use storage device for decades after the introduction of the KH-11, leading to the irony that a digital satellite ultimately required film on the ground.

| Film remained a powerful and easy to use storage device for decades after the introduction of the KH-11, leading to the irony that a digital satellite ultimately required film on the ground. |

According to Jeffrey Richelson in The Wizards of Langley, the first KENNEN, launched in December 1976, used light-sensing diodes to collect the light reflected from the target. But the next satellite, launched in June 1978, used charge-coupled devices. The CCD had originated at Bell Telephone Laboratories, invented by Willard S. Boyle and George E. Smith, who received the Nobel Prize for it in 2009. The CCD had been demonstrated in 1970, but Boyle and Smith’s device was created for memory storage. Their colleague, Michael F. Tompsett, patented the CCD as an imaging device in 1972. Tompsett’s patent was for both line imaging and area imaging devices. Tompsett also invented another silicon-based imager that he claimed “never saw the light of day” because it was eclipsed by the CCD.[78] Perhaps that silicon-based imager is what flew on the first KENNEN satellite, only to be replaced by the CCD. CCD’s had also found other telescope uses. In 1975, scientists from JPL and the University of Arizona began using a CCD with a 61-inch (1.55-meter) telescope to image planets.[79]

KENNEN’s specific technologies and operational history remain classified. Some information on the early history of the program has been reported in books and articles, indicating that KENNEN apparently suffered some operational problems in early years. Its travelling wave tube amplifiers, a key component in the communications system, wore out quicker than planned. They also were so power hungry they drained the satellite’s batteries faster than they could be recharged by the solar panels, thus limiting operations to only two hours per day.[80] There were allegedly also problems with data relay and claims that the data relay satellites were not where they were supposed to be when the KENNEN satellites were transmitting. This may have prompted a reorganization of management responsibilities for the KENNEN and data relay satellites for better operational coordination of the two satellites. But KENNEN worked from the start, which is how the inauguration photographs had ended up on President Jimmy Carter’s Oval Office desk in January 1977. Had Nixon not been threatened with impeachment and resigned from office, he would have seen KENNEN’s photographs before the end of his term.

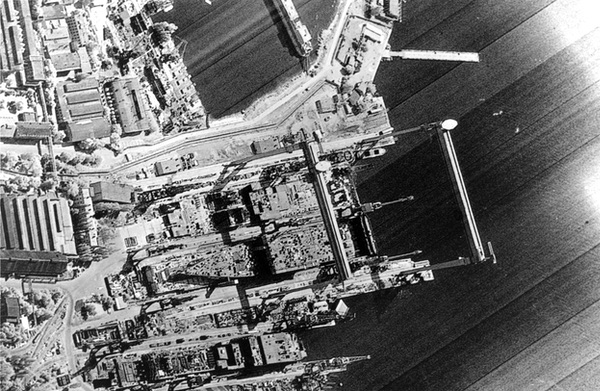

Leaked image of a Soviet aircraft carrier under construction in the early 1980s. The person who leaked this image to the news media later went to prison. |

KENNEN did not remain secret for long after it entered operation. In late 1977, an intelligence analyst named William Kampiles stole the KH-11 System Technical Manual from his workplace and sold it to Soviet military intelligence for $3,000. Leslie Dirks, who had been charged by Bud Wheelon in 1963 with pursuing the technology to enable a near-real-time reconnaissance satellite, found himself in the unusual position 15 years later of talking about it in public. In November 1978, Dirks went to court to testify about KENNEN during Kampiles’ trial. Dirks explained the basic operations of the satellite and the fact that revealing its capabilities could do great harm to national security. Kampiles was found guilty and sentenced to 40 years in prison.[81] His sentence was later reduced and he was released in December 1996. In the 1980s, a naval analyst released KH-11 photographs of a Soviet aircraft carrier under construction. He too went to jail. The KENNEN was upgraded several times and renamed more than once. By the 1990s degraded images taken by the satellites were occasionally released for policy purposes.

One of the surprising aspects of the story of the quest for near-real-time reconnaissance satellites is that requirements for warning intelligence and crisis reporting did not drive decision makers to move any faster. If these had truly been pressing requirements—and the Czechoslovakia experience was a great motivator—then FROG would have received a go-ahead earlier. But FROG was rejected in 1966 and did not receive approval until April 1971, only to be canceled five months later. Clearly, nobody in a position to make near-real-time satellite reconnaissance happen after the August 1968 Czechoslovakia invasion believed it was an urgent requirement.

Rather than a clear desire for warning intelligence, the development of the KH-11 KENNEN satellite appears to be an example of technology driving the decision-making. KENNEN’s electro-optical imaging technology was clearly superior to film-readout, and senior intelligence officials were willing to wait until it was mature enough to deploy rather than proceed with something that would cost less but never be as good. Compared to FROG, KENNEN was also expensive, relying upon all-new technology, bigger rockets, and a constellation of relay satellites operating in much higher orbits. The actual costs of the KENNEN system remain classified, but Richelson wrote in The Wizards of Langley that the system did not substantially exceed its 1971 cost estimates.

For Air Force officers in the NRO in the early 1970s, the ultimate rejection of FROG in favor of ZAMAN must have been particularly galling, and yet totally, frustratingly familiar. SAFSP/Program A had lost many bureaucratic battles against the CIA’s Office of Development and Engineering/Program B. In the mid-1960s, the Air Force search satellite had lost out to the CIA’s HEXAGON search satellite. In 1969, the CIA’s HEXAGON had been canceled in favor of the Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory and its DORIAN reconnaissance camera, only to have Nixon reverse that decision when the head of the CIA appealed directly to the president. Now once again the Air Force’s preferred reconnaissance system had been approved, only to be canceled a few months later in favor of the CIA’s system. In official histories as well as documents and memos, an air of depressed resentment towards the CIA by Air Force members of the NRO is often apparent; even when SAFSP won, they eventually lost.

Demonstrating what appears to be subtle but devastating wit, Lew Allen later wrote that “a remarkable piece of KENNEN history is the awesome effectiveness with which CIA and the Land Panel dedicated themselves to supporting KENNEN once Land made his basic commitment. The only parallel in history is the unified dedication of the Romans to the destruction of Carthage.”[82]

An image produced by later American near-real-time reconnaissance satellites. These images have been degraded from the maximum performance of the satellite. (credit: Department of Defense0 |

According to a former NRO official, CIA reconnaissance officials—whom many of the Air Force officers working in the NRO respected for their knowledge and intellect—rarely missed an opportunity to be jerks about their victories. Colonel Ralph Jacobson had been one of the primary proponents for FROG during the 1960s. Years later, as a general, he became the Director of SAFSP/Program A and had the opportunity to battle—and lose—some more to the CIA’s Program B. In 1983, Program A was responsible for the GAMBIT and HEXAGON film-return programs, both of which were then flying their last satellites on the way to retirement. When Jacobson took over, he got two packages from his CIA counterpart. They were small caskets. In one was a ceramic GAMBIT figurine, in the other was a ceramic HEXAGON figurine. It was like a mobster receiving the gift of a dead fish from a rival.

The rivalry between the Air Force and the CIA within and about the National Reconnaissance Office was not an abstraction or merely a power struggle, it was about systems, hardware, money, and who would define the requirements and build the systems—and the CIA kept winning. As the retired NRO official remembered an Air Force colonel once telling him, “The Russians are merely the threat, Program B is the enemy!”[83] The KH-11 KENNEN was another battle in their long conflict, and a true victory for the CIA.

Endnotes

- Robert Perry, “NRO History: NRO history Series Chapter 17, Vol. IV, Draft Only,” [version approved for release 3-19-2018], pp. 52-53.

- Perry, pp. 53-54.

- Perry, ibid.

- Perry, p. 55.

- Perry, p. 56.

- Perry, p. 56.

- Perry, p. 83.

- Perry, p. 57; 90.

- Perry, p. 59.

- Perry, pp. 60-61.

- Perry, p. 61.

- Perry, pp. 61-62.

- Perry, p. 62.

- Perry, p. 63.

- Perry, p. 64; 66.

- Perry, p. 68.

- Perry, p. 69.

- Perry, pp. 70-71.

- Schlesinger was a fast-rising star. He became acting deputy director of OMB, then chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission, briefly Director of the CIA, and in January 1973 he became Secretary of Defense.

- Perry, p. 72.

- Perry, pp. 72-73.

- Perry, p. 74.

- Perry, p. 75.

- Perry, pp. 76-77.

- Perry, p. 87. See also: Dwayne A. Day, “Shadow Dancing: The Satellite Data System,” The Space Review, February 26, 2018.

- Perry, p. 77.

- Perry, p. 79.

- Perry, pp. 80-81.

- Perry, pp. 81-82.

- Perry, p. 83.

- Perry, p. 84.

- W.F. Craig, Memorandum for Dr. McLucas, Subject: Ray Cline’s Views on Crisis Response, n.d., (but January 1971).

- Perry, p. 86.

- Perry, pp. 87-88.

- Perry, pp. 88-89.

- Perry, p. 91.

- Carl E. Duckett, Director, CIA Reconnaissance Programs, to Dr. John McLucas, Director, National Reconnaissance Office, January 21, 1971.

- McLucas, Memorandum for Mr. Packard, Subject: Actions Approved at the ExCom Meeting (23 April 1971), June 4, 1971 w/att: Some ExCom Thoughts.

- Ibid.

- Oder, Fitzpatrick, Worthman, The GAMBIT Story, p. 92; John L. McLucas, Memorandum for Mr. Packard, Subject: Actions Approved at the ExCom Meeting (23 April 1971), June 4, 1971 w/att: Some ExCom Thoughts.

- Perry, pp. 92-93.

- Perry, pp. 93-94.

- Perry, p. 94.

- Dr. McLucas Charge for Gen. Allen, “Film Readout GAMBIT (FROG),” April 26, 1971.

- Perry, p. 95.

- General Allen to Dr. McLucas, “Interim System Film Readout GAMBIT Status,” April 30, 1971.

- L. Allen to E. Sweeney, April 29, 1971.

- From [deleted] to [deleted]/Cohen, “Some informal thoughts on FROG establishing baselines as I see them from Washington,” May 3, 1971.

- Robert A. Schow, Jr. Memorandum for Colonel Sweeney, “GAMBIT improvements versus FROG development,” May 3, 1971.

- Perry, p. 96.

- Oder, Fitzpatrick, Worthman, The GAMBIT Story, p. 92; Memorandum for the President’s File, Subject: President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, Meeting with the President, June 4, 1971.

- Perry, p. 100.

- Perry, p. 101.

- Perry, p. 102.

- Colonel David D. Bradburn, USAF, Director, NRO Staff, Memorandum for Dr. McLucas, “Highlights of the Land Panel Meeting, 11 June 1971,” June 14, 1971.

- Perry, p. 103.

- Perry, pp. 97-98.

- Perry, pp. 95-96.

- Erin R. Mahan (ed.), Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976, Volume XXXII: SALT I, 1969-1972 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 2010), pp. 521-522.

- Ibid., p. 523.

- Ibid., p. 523.

- Ibid. pp. 523-524.

- Perry, p. 99.

- Perry, pp. 105-106.

- Perry, p. 106.

- Perry, p. 107.

- Perry, p. 108.

- Perry, p. 111.

- Perry, p. 114.

- Perry, pp. 115-119.

- Perry, p. 116.

- Perry, p. 109. [The unnamed observer’s comments are included in Perry’s handwritten notes on the unnumbered page between 109 and 110.]

- Perry, p. 114.

- Perry, p. 121.

- Oder, Fitzpatrick, Worthman, The GAMBIT Story, pp. 92, 185; Henry A. Kissinger, Memorandum, Subject: Near-Real-Time Satellite Reconnaissance System, September 23, 1971.

- [Author Name Redacted], EXRAND, “Minutes of Meeting Held in IAS Conference Room 0900-1130, Thursday, 30 September 1971,” October 7, 1971, CREST; Lt. Col. Frederick L. Hofmann, Office of the Secretary, Department of the Air Force, Memorandum for the Record, Subject: The Birth of a BYEMAN Codeword, November 24, 1971.

- Perry, p. 122.

- “Nobel Controversy: Former Bell Labs Employee Says He Invented the CCD Imager,” IEEE Spectrum, October 8, 2009. https://spectrum.ieee.org/tech-talk/semiconductors/devices/nobel-controversy-former-bell-labs-employee-says-he-invented-the-ccd-imager

- Jeffrey T. Richelson, The Wizards of Langley, Westview Press, 2001, p. 199.

- Richelson, p. 201.

- Richelson, pp. 205-208.

- Perry, Intro p. 6.

- Email to Dwayne Day, December 27, 2017.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.