Our unknown solar systemby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Just as oceanic travel did not become safe or reliable until meteorologists learned to understand the basics of Earth’s weather patterns, we will need to understand the natural forces driving space weather if space travel is to become routine, safe, and reliable. |

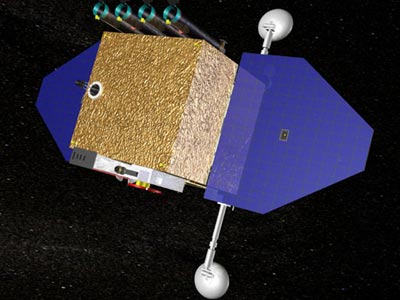

When it arrives in its planned inclined geosynchronous orbit, it will replace the invaluable SOHO satellite, which has been kept going through the heroic efforts of a combined NASA/ESA team. Its Extreme Ultraviolet Variability Experiment (EVE), managed by the University of Colorado at Boulder, will continue the work of SOHO’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imaging Telescope (EIT). SDO’s other two instruments are the Helioseismic and Magnetic Imager (HMI), managed by Stanford University, and the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA) controlled by Lockheed Martin. The principal goal of the mission is to develop a basis for understanding and predicting important solar activity. This includes the 11-year solar sunspot cycle and the 22-year solar magnetic cycle.

There is so much that we do not understand about the way the Sun’s magnetic field interacts with various layers of its atmosphere. The SDO mission should be looked on as just a minimal down payment on the investment that will eventually be needed. Just as oceanic travel did not become safe or reliable until meteorologists learned to understand the basics of Earth’s weather patterns, we will need to understand the natural forces driving space weather if space travel is to become routine, safe, and reliable.

Once SDO is operational the data flow will be substantial and, given the urgent need to improve the US government’s overall ability to predict space weather, NASA leadership should insure that the researchers who will be interpreting the data have all the resources they need to do the job in a timely fashion. This is not a case where the usual leisurely pace of scientific investigation is acceptable. Planning for this should begin now.

Eventually NASA (and no other space agency is going to do this) is going to have to build a set of “Solar Sentinels”. These were proposed as part of the original LWS program back in 2000, but they were later put on the back burner. They were a set of small spacecraft to be placed in obits around the Sun where they would track solar activity in three dimensions and in near real time. One fascinating aspect of the project was the idea that they be propelled by solar sails.

| It is logical to assume that understanding the solar system environment is just as important to the vision as building the next generation of manned spacecraft. NASA and Congress should be able to balance these requirements without having to make any major cuts in the solar system exploration plans. |

Beyond SDO and the Solar Sentinel missions there is a need to get up close and personal with the Sun; here the missions to Mercury have great potential. The NASA MESSENGER probe launched last year will arrive in orbit in March 2011. Its instruments have been designed to answer question about the nature of the planet itself, but after the initial mission objectives have been attained it will be interesting to see if they may be used to collect data that will be of direct interest to the LWS and space weather investigators. Certainly if MESSENGER can be kept operational for a long time in the extreme temperature and radiation environment around Mercury, it could be a valuable asset for those who need keep an eye on our local star.

Eventually it might be advantageous to establish a large, automated, nuclear-powered rover or solar observatory on the surface of Mercury. This would be a permanent part of a space weather network that would provide much better early warning for solar storms than what is now available.

Some claim that the exploration vision requires that NASA give up its space science objectives in order to concentrate on building systems such as the CEV. In fact, it is logical to assume that understanding the solar system environment is just as important to the vision as building the next generation of manned spacecraft. NASA and Congress should be able to balance these requirements without having to make any major cuts in the solar system exploration plans. Robots and humans are both needed to accomplish these goals. It should not be that hard to fit these needs into future NASA budgets.