Giant leaps for humanity: Liberalism for a multiplanetary speciesby Ian McCann

|

| Property rights are a cornerstone of liberal democracy everywhere, and that will hold no less true in space. |

Progressives and socialists will be elated that all walks of life will finally start getting access to the great common that is the cosmos, and that the technology derived for and from these missions will be used to advance society in an ever better direction, helping to fight oppression and secure social justice along the way. Neoliberals will be overjoyed about the possibility of asteroid mining creating untold wealth for humans all around the solar system, greatly expanding markets and their potential and perhaps finally allowing us to banish scarcity for good. Libertarians will be enthusiastic at the prospect of leaving coercive governments on Earth and being able to secure more terra nullius, or finally being able to float in the great deep of space without any outside interference. Capabilities liberals will be delighted to know that humans will be adding the new capability of choosing on which planet one wants to live within the next century. In all, there’s nothing not to like about our proliferation across the planets for liberals, and 50 years after the first Moon landing it’s about time we start picking up the steam in that regard.

But this leads to a question of how best to colonize space. It’s a good thing that the Moon Treaty is dead letter, as much as it still lurks in the shadows (see “The Moon Treaty: failed international law or waiting in the shadows?” The Space Review, October 24, 2011). Property rights are a cornerstone of liberal democracy everywhere, and that will hold no less true in space. Indeed, the practical infinitude of space, and the large amount in land available on the Moon and Mars in particular, offers an escape from the inelasticity of such capital as land that can lead to oppression. The cosmos is beckoning, and offers the opportunity of peaceful and free anarchy.

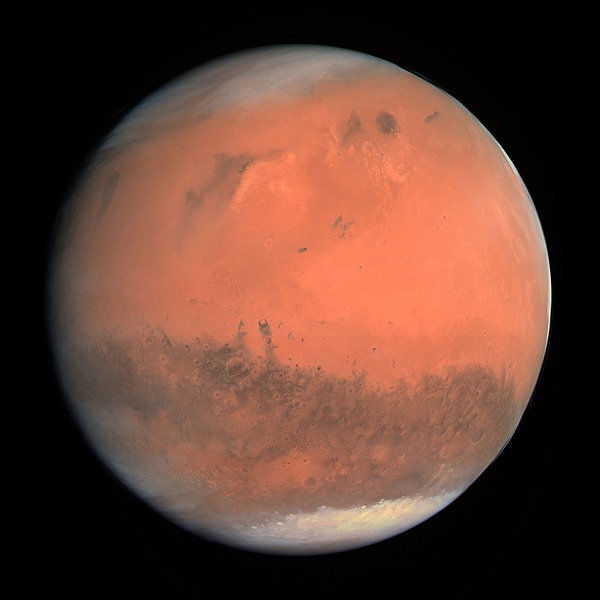

On the other hand, settlement of the Moon and Mars will probably need to be ordered on some level. Any terraforming of Mars will need to be the effort of a body with coercive power, which would likely but not necessarily be a state. Like other public goods such as roads, I don’t think that the market for all of its potential can produce a coherent terraforming strategy. Much as I share Hayek’s aversion to centralized decision-making, I think that the science of climate, even here on Earth, is sufficiently complex to the point where some plan is in order, and I’m confident that the goal, however lofty, is narrow enough to spare us from any road to serfdom. I am of the opinion that a pan-Martian Mars-based state or collective would be the best to do this job; any Earth-based and Earth-directed terraforming effort would be imperialistic folly at worst, doomed to failure without any information on the ground and, at best, capable of engendering local resentment, although scientists from the mother planet would still probably play a part in this grand undertaking.

| The idea that we should solve problems here on Earth before we concern ourselves with space travel suffers from the same zero-sum, either/or mentality that underlies many illiberal thoughts and ideologies. |

I think a large part of the answer to this apparent conundrum might be to separate the concepts of space in general and other celestial bodies in particular. The former is simply an extension of the open sea, and as such all the conventions and customs of the ocean can be extended to the cosmos with little if any modification. Space capsules and space stations are glorified ships and should be, and are, treated as such. The Moon and Mars, on the other hand, is much more like countries on land, with constant volume that can be parceled out and given to private individuals. Yet current space law doesn’t appear to distinguish between the two. Article II of the Outer Space Treaty treats them collectively, banning nations from claiming sovereignty over “outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies.” This might have made sense in the 1960s when the treaty was signed, but modern reality renders it anachronistic. To the extent that liberalization of space law needs to happen, it’s with respect to terrestrial planets.

I would be remiss, of course, if I didn’t mention and address the various concerns that have been raised with regards to space exploration. The first is the idea that we should solve problems here on Earth before we concern ourselves with such travels. Notwithstanding the fact that this de facto precludes any sort of space travel given the infinitude of such ills, it suffers from the same zero-sum, either/or mentality that underlies many illiberal thoughts and ideologies. Indeed, technologies developed for or during space exploration have been themselves used to solve issues on Earth. Starlink is itself an example that improves Internet access for people worldwide.

There are, however, better arguments against space travel. Space travel is inherently risky, and Musk knows this when he says that “people will die” on the way to Mars. While this is certainly an unfortunate consequence of a new and hostile environment, so long as the astronauts are well aware of the risks they get into and nevertheless go on such missions on their own free will, it is a commendable sacrifice on their part. This is not to say that safety on these missions is not indispensable; cavalier management on the part of NASA was the main factor in the Challenger disaster and significantly contributed to the fate of Columbia and her crew. Space agencies and rocket companies have a moral obligation to provide for the safety of their crew to the extent practical, if not above and beyond. Nor is this to minimize the challenges in comfort and adaptation to the space environment people face on spaceflight in addition to these risks. Nevertheless, the fact that people will unfortunately perish on this great adventure is not in of itself reason to abort the missions and stay back on Earth.

| This monumental expansion provides unprecedented capacity for liberalism and the growth of the human spirit, and is a great triumph of humanity. |

The best argument against space travel is that it increases the risk of war and its consequent evils. This is the motivation for signing such documents as the Outer Space Treaty and attempts to limit space exploration that have taken place since, including the Moon Treaty. I unfortunately cannot guarantee that such things will not happen. But we can hope that the possibilities of space travel provide enough challenge and adventure that aggressive energies will be redirected to something far more constructive and provide a “Moral Equivalent of War” that is not, in the immortal words of Edwin Starr, “friend only to the undertaker”. Indeed, it is widely recognized that the challenges of extraterrestrial travel are such that international cooperation is all but compulsory.

By the time this century is out, it is far more likely than not that humanity will be a multiplanetary species; eventually space travel will become as commonplace and convenient as air travel is today. This monumental expansion provides unprecedented capacity for liberalism and the growth of the human spirit, and is a great triumph of humanity. It will not be without its struggles and unique challenges, but these will be more than outweighed by the immense opportunities and capabilities of brave new worlds. This will be an exciting era for liberalism and humanity.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.