The rocketeer who never wasby Mark Wade

|

William Swan |

But who was Swan? He only seemed to have existed for four years. He appeared out of nowhere and married into a prominent Maryland family in 1929. At Boca Chica, it was said people were waiting at the other side of the border to take him to a new life in Mexico. Where had he come from? Where did he go? It was only in the 21st century, through DNA testing, that the life story of Swan was revealed.

Before Swan

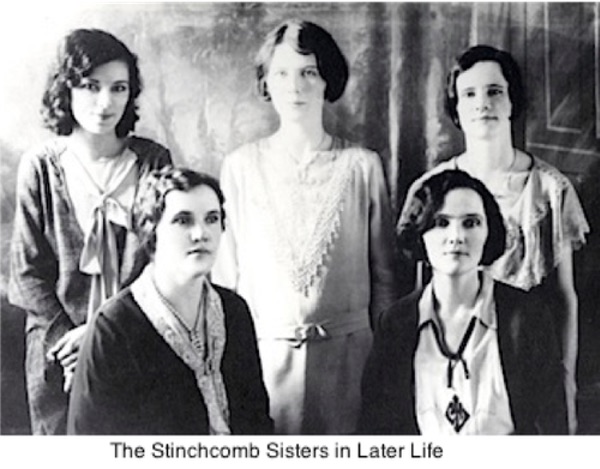

Swan was born William Dewey Stinchcomb on a farm in Jackson County, Georgia, on May 19, 1902. The only boy among five sisters, he was already listed as a farm hand for his illiterate father at the age of 8. He left home and his family before becoming a teenager and they never heard from him again.

| He later claimed to have been a barnstormer, parachutist, and Hollywood stunt pilot, but there is no evidence for this. |

Lying about his age, he enlisted at age 14 with the US Navy on November 11, 1916. He served aboard the newly-commissioned battleship USS Nevada but was discharged on August 4, 1917, after only 120 days of duty. Perhaps his true age was discovered, or there were disciplinary problems. He may have served 18 months on a Georgia chain gang for grand theft auto from August 23, 1919.

|

Not long after release he shows up in Washington, DC, under the slightly altered name of John William Stinchcomb. He fathered a stillborn daughter with Marguerite Liston, a government clerk, on September 13, 1922. Six years later, on May 23, 1928, a son, Richard Liston Stinchcomb, was born to the same couple. Somehow during these six years he learned to fly, mastered aircraft construction, and evidently assumed genteel manners. He later claimed to have been a barnstormer, parachutist, and Hollywood stunt pilot, but there is no evidence for this. Soon after the birth of his son he disappeared from the lives of Marguerite and Richard.

Becoming Swan

Somehow he met Huldah, the granddaughter of Senator George Lewis Wellington of Maryland. He told her that he was William Gaylord Swan, son of the deceased but prominent Colonel William Swan of Atlanta. Huldah was sent on a trip to the Park Regency Hotel in London in April-May 1929, chaperoned by her aunt, possibly to separate her from Swan. But by August she found out she was pregnant. Her marriage to Swan was announced on September 6, and they were married in a big society wedding on October 30 at her parent’s home in Cumberland, Maryland. She had their son, John Wellington Swan, in seclusion in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, on April 17, 1930.

Huldah Swan |

Swan seems to have been employed by manufacturers to flight test or ferry aircraft from their factories. Investors, or his new wife’s money, allowed him to indulge in the life of an aviation pioneer. He built an aircraft simulator for use in flight training. Perhaps the image of a pioneering aviator assuaged any concerns Huldah’s parents had about their new son-in-law. Huldah would accompany Swan on some of his flights and this glamorous life style was fed to the local newspapers. In August 1930, they flew from her parent’s home to Seneca, New York, with Swan flying one of the new Mercury Chic monoplanes.

Rocketeer

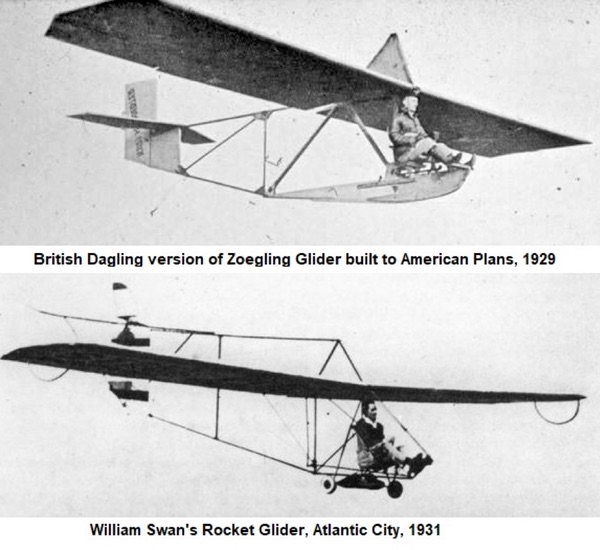

Swan conceived of building a rocket-powered glider, setting up shop in Atlantic City by March 1931. His rocketplane was a modification of the Zoegling Primary Training glider invented in Germany by Hans Lippisch in 1926. These resembled modern hang gliders, with a wire-reinforced open strut structure suspended under the wing. They were launched using bungee cords pulled taut by teams of eight fellow glider enthusiasts. Zoegling clones were built by several companies in the United States by 1929, and plans were available for home builders.

|

Swan’s design required substantial modification for rocket flight. The landing skid was replaced by a tricycle undercarriage. Swan angled the entire structure aft of the wing upwards to clear the tail from the exhaust of the rockets mounted below the pilot’s seat. This required the struts to be extended in a straight line aft of the wing brace.

| The single rocket Swan ignited could have added, at best 4 mph (6.4 km/h) to the glider’s speed. |

Lippisch, with financing from Opel, had built two rocket-boosted glider designs in Germany in 1928 and 1929. Both had successfully flown but were detroyed in crashes after a few flights. Swan’s aircraft was more primitive than the Lippisch designs, but he built them to take the same number and thrust of powder rocket motors.

Swan had arranged to launch the glider from Atlantic City’s Steel Pier. This had opened in 1898 and was a prototype of the modern amusement park. It was equipped with theaters, cinemas, sideshow attractions, trapeze artists, and showcased the top entertainers in the country. Visitors paid one flat price to access all the concerts, films, and attractions for the day. In 1931 exciting new attractions were added, including boxing cats, parachute jumping, an autogyro aircraft, and Swan’s rocket-powered glider.

|

Swan was doing other flying work on the side, but without Huldah, who was pregnant again. On May 24, 1931, he claimed to have narrowly escaped death in a forced parachute jump when the wing of a plane he was flying back from Trenton ripped as he was nearing Columbus.

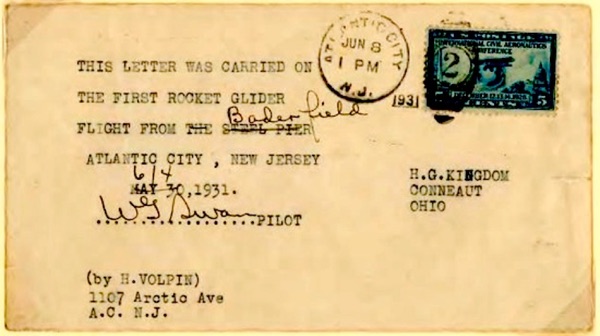

The first flight from the Steel Pier was scheduled only six days after this dramatic incident. But it seems that either the Pier management, local authorities, or Swan himself decided it would be better to first test the rocket glider at an airfield. The test was moved to Bader Field in Atlantic City and delayed to June 4, 1931.

Rocket post showing change of date and location for first flight |

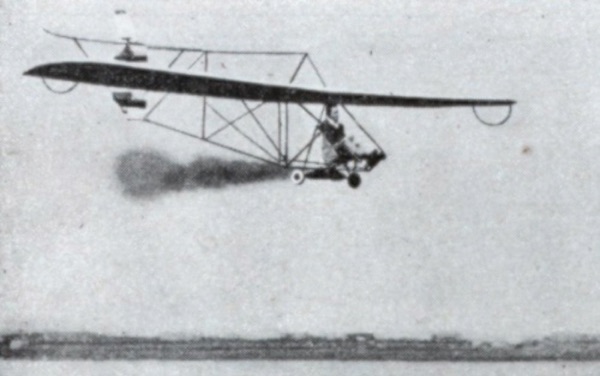

The flight was documented by the New York Times the next day. Swan took off in the afternoon. The 200-pound (90-kilogram) aircraft (less Swan’s weight, so about 350 pounds total) was equipped with a single 50-pound-thrust (220-newton) rocket engine. A ground crew gave the aircraft “a push takeoff. When the glider had attained some momentum Swan pulled an electric switch, firing off the rocket with a loud explosion. The craft rose into the air, riding bumpily at first, then soaring. Swan came to the ground with a perfect landing.” Swan reached an altitude of 100 feet (30 meters) and flew 1,000 feet (300 meters) down the runway in the test hop. It was noted that “the gilder, designed to entertain Steel Pier crowds this summer, will be equipped with pontoons, and flights will be made several times daily.”

| His plan was “to pierce the stratosphere at an altitude of 40,000 feet and fly across the Atlantic at a speed of more than 500 miles per hour.” |

We don’t know what kind of rocket Swan used. Many in those days were home built, using a press to compact the fuel, often resulting in explosions. A typical 50-pound-thrust black powder rocket of the period produced an average of only 20 pounds (90 newtons) of thrust for three seconds. This means the single rocket Swan ignited could have added, at best 4 mph (6.4 km/h) to the glider’s speed. So the glide would have to be attributed to the conventional human-powered launch, not the rocket. But it did demonstrate the ignition of the engine.

|

On the next morning, Swan went ahead with a full-scale test. Again a ground crew got the glider into the air. The glider was equipped with 12 of the 50-pound thrust rockets, enough to boost it to more than 50 mph (80 km/h). He reached 200 feet (60 meters) altitude, then stayed aloft for 8 minutes before landing on the runway.

These two original news stories were mixed and garbled as repeated across the nation. A very garbled version became part of the NASA official chronology: “1931 January 4: William G. Swan stayed aloft for 30 minutes over Atlantic City, NJ, in a glider powered with 10 small rockets.”

It is not known if Swan actually flew the pontoon-equipped glider from the Steel Pier. Perhaps it was attempted, using a catapult to throw the glider off the end of the pier. It is known that on July 12, 1931, Swan was featured in a newsreel, “diving a plane into the Atlantic Ocean at Atlantic City.”

After the summer, Swan was back to more conventional pursuits. On September 4, 1931, it was reported that he lost his way flying from New York to Cumberland, crash landing on a farm, before continuing on to Everett, Pennsylvania, for fuel. Over the winter the Swans visited her parents in Cumberland twice. On February 20, 1932, their second son, Gordon Gaylord Swan, was born.

Air launch

By the summer, Swan left his family behind, and hit the road. On July 18, before a crowd of 5,000 at Exposition Park in Aurora, Illinois, Swan had his glider taken aloft by a hot air balloon. At 2,000 feet (600 meters), he released the glider. He stated that a rocket motor was then ignited, although no smoke is visible in the newsreel footage. After four minutes he landed safely. Swan announced that “his plans call for the construction of a combination balloon and rocket plane. A number of balloons for this purpose are already under construction.” His plan was “to pierce the stratosphere at an altitude of 40,000 feet and fly across the Atlantic at a speed of more than 500 miles per hour.”

|

Despite these claims it is not clear if Swan even used the rocket except as a prop in the stunt. However, newsreels gave him nationwide coverage.

There were claims that Swan flew over Washington in January 1933 as part of the inauguration of President Franklin Roosevelt, but there is no documentation of this. In fact, by this point in time he was running out of money, again trapped in a marriage with young children. He claimed to have hundreds of stunts under his belt, including 300 parachute jumps, but no work was being offered.

|

The end of Swan

By April 1933, Swan lined up an agreement with a newspaper for a spectacular stunt in Texas. As part of a skydiving exhibition at the Del Mar Beach Resort on Boca Chica, he worked out an elaborate routine. He would bail out of a aircraft, dropping flares and rockets on small chutes as he was in free fall. Finally he would ignite a rocket strapped to his back and head toward the beach, to land in front of the crowd. He arrived as agreed, but was nearly penniless, temperamental, and moody. He told the owner of the Del Mar that he was “down on his luck” and wanted to settle down with his family back in Maryland. He asked for an advance of $20 to tide him over. He got the money, but there were further problems getting an aircraft and pilot. Finally, a Command-Aire crop duster was located, and Texas aviation legend Slats Rodgers agreed to take him up.

| Swan had either died through miscalculation, intentionally committed suicide, or had successfully started yet another life in Mexico. |

The day of the flight was cloudy, foggy, and depressing. The sun finally broke out at 3 pm. A crowd of 3,000 cars was expected, but only 1,086 came. Before Swan went up “he realized that advertising, fire works, rent of plane and other heavy expenses would exceed the income at the toll gate. He told a friend he would not make a cent on the stunt, but he would carry out his contract and give his audience their money’s worth.” But he may have had other plans to get out of his situation.

|

Rodgers finally took off in the gloom near sunset. Swan was atop the hopper, with a cigar in his mouth to ignite the fireworks. Inexplicably, Swan directed the pilot well out to sea, far from the crowd on the shore. Rodgers could smell that the cigar in Swan’s mouth had gone out. Swan urged Rodgers to fly farther and higher, then unexpectedly bailed out at 8,500 feet (2,600 meters). As the pilot spiraled around him during his descent, he saw that Swan released the small flares, which did not ignite. Swan’s rocket didn’t fire either. His parachute opened at 6,000 feet (1,830 meters). He waved at Rodgers but made no move to manipulate the lines to head toward shore. He disappeared into the clouds and mist well out to sea.

Newspaper accounts spoke of Swan telling some that he intended to land, cut off his chute, and go into hiding. They also spoke of two cars parked against the water on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande, the occupants anxiously watching the skies. But subsequent searches did not find his body or the parachute. His wife was notified of his death by the resort owner. Swan had either died through miscalculation, intentionally committed suicide, or had successfully started yet another life in Mexico.

|

Aftermath

Huldah was greatly “affected” by the news of her husband’s death. We cannot know if she knew or suspected of his earlier identities, the lies about his career, his other family in Washington, or of his plans in Texas. We may imagine the emotional burden of defending her husband to her parents, the premarital pregnancy and forced marriage, and finally being left alone with two small children. On December 8, 1933, nine months after Swan had bailed out over the Gulf of Mexico, Huldah was “taken ill” and put in the hospital. She was diagnosed with agranulocytosis, a dangerous low white blood cell count. This is most often caused by certain drugs. Despite efforts to save her through blood transfusions from family members, she died on December 12.

Secrets Revealed

Her sons were raised by her parents. One became a prominent Air Force officer. Before he passed on, a DNA test linked him to his secret half-brother, Richard Stinchomb. Only then were the multiple lives of William Swan revealed. Most likely he died off Boca Chica in 1933. But having already led four lives in only 31 years, perhaps he lived out yet more in Mexico. One Stinchcomb family obituary suggests he may have been living in Montreal decades later. But Swan could never have imagined that his last flight would be the likely scene of humanity’s departure to Mars less than 100 years later.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.