The challenges facing Artemis in 2020by Jeff Foust

|

| “We asked for a billion dollars for the Human Landing System, and we got $600 million,” Bridenstine said. “Now we’ve got to go back and see what we can adjust.” |

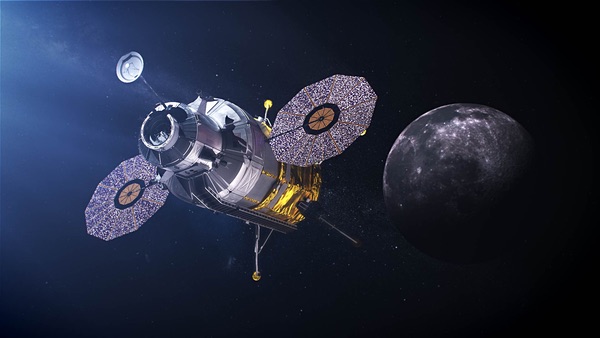

A lot changed in the succeeding nine months, such that by the end of 2019 much of what was now called the Artemis program was taking shape. Most of what will needed to carry out the first human landing in 2024 is now under contract or soon will be. Some, like the Space Launch System and Orion, had been in development long before Artemis (in the case of Orion, dating back to the Constellation program to return to the Moon in the early 2000s.) NASA awarded a contract to Maxar to develop the first element of the Gateway, the Power and Propulsion Element, and announced its intent to award a sole-source contract to Northrop Grumman for a second Gateway module, the Habitation and Logistics Outpost.

The last major component for that initial Artemis lunar landing mission is the lander itself. NASA solicited proposals for development of the landers as public-private partnerships in the fall, and received proposals from several companies, including Boeing and a “national team” of Blue Origin, Draper, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman, and likely from SpaceX as well (see “Coming together to go to the Moon”, The Space Review, October 28, 2019). NASA plans to award initial contracts as soon as this month, ultimately selecting one or two companies to proceed into full-scale development.

That doesn’t mean the path will be smooth. One key issue arose last month, when Congress reached a deal on a final spending bill for fiscal year 2020. NASA received $22.63 billion in the bill, about in line with its original request of just over $21 billion plus the $1.6 billion budget amendment submitted to Congress in May.

However, the allocations in the bill don’t line up with the administration’s request. While programs like SLS and Orion received more than requested, the lunar lander program, for which NASA sought $1 billion in 2020, received only $600 million.

That shortfall could put a squeeze on what NASA is able to do with the lunar lander program. Agency leaders, like administrator Jim Bridenstine, previously suggested that if NASA didn’t get the full $1 billion, it would have to scale back its plans, perhaps awarding fewer contracts or downselecting to a single contractor early.

| “NASA is ill-positioned to explain how it arrived at its current lunar architecture without a comprehensive assessment that documents how NASA decided that its current plans are the best way to meet the agency’s long-term lunar exploration goals,” the GAO concluded. |

NASA hasn’t disclosed how it will address that shortfall in the program. “We asked for a billion dollars for the Human Landing System, and we got $600 million,” Bridenstine said during a Dec. 19 press conference at the Kennedy Space Center ahead of the uncrewed test flight of Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner spacecraft. “Now we’ve got to go back and see what we can adjust.” He added that NASA might adjust its fiscal year 2021 budget proposal in response to the reduced funding in 2020.

Prior to the completion of the funding bill, when it was uncertain how much, if any, funding would be allocated for human lunar landers, Bridenstine said he was open to looking at ways to use other programs, like the Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships (NextSTEP) and the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program for commercial robotic lunar landing services, to support human lander development. “We’ve got to look at creative ways where we can keep moving forward, even in this very politically charged environment,” he said in a Dec. 10 interview.

The same day Bridenstine was talking at KSC about funding human lunar landers, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) came out with a report assessing the state of the Artemis effort. “NASA has identified the components of its lunar architecture—such as Gateway and lunar landers—but it has not fully defined a system architecture or established requirements for its lunar mission,” it noted in the report.

The report noted that NASA is still working on the overall architecture and requirements, which the GAO report noted risked creating mismatches at the project level. For example, the report stated there is a difference between the amount of power the PPE is required to produce under NASA’s contract with Maxar and the Gateway’s power requirements. NASA is addressing that through efforts like a “lunar exploration control board” to handle configuration management and “synchronization reviews” among programs involved in Artemis.

Then there is the issue of cost. NASA has yet to produce an estimate of how much the Artemis program will cost through the Artemis 3 lunar landing mission in 2024. In a June interview, Bridenstine said NASA would need $20–30 billion over its existing budget profile to achieve that landing, although he subsequently backed away from it and suggested it could be done for less than $20 billion.

The GAO report added to the confusion about the cost of the program. “The NASA Administrator made a public statement that the Artemis III mission may cost between $20 billion and $30 billion, but NASA officials told us they do not plan to develop an official cost estimate for the Artemis III mission,” the report stated. That cost estimate, though, was widely understood to be for the entire Artemis program through the Artemis 3 landing mission, and not the mission itself, as the report states.

NASA, in a response included in the report, said it would provide a preliminary estimate of the cost of Artemis 3 by the end of 2020. That would come once it makes cost and schedule commitments for the Human Landing System program and achieves milestones in other elements, like the lunar Gateway, needed for the mission.

| “How can anybody how cares anything about space not go ahead and jump at the opportunity to put women and men back on the Moon?” Loverro said about taking the NASA job. |

We may know even sooner, though, how much NASA expects the initial phase of the Artemis program to cost. The administration will release its fiscal year 2021 budget proposal in early February—the current estimated release date is February 10—that will include the funding request for NASA. Those budget proposals traditional include not just the request for the upcoming fiscal year but also “outyear” budget projects for up to five years. That could mean the proposal will include budget estimates through fiscal year 2025, encompassing an Artemis 3 mission by the end of calendar year 2024. (However, in some years those outyear projection have been flat or “notional,” and not intended to represent any firm estimates.)

The GAO report overall was critical at the lack of rigor it saw in NASA’s planning. “NASA is ill-positioned to explain how it arrived at its current lunar architecture without a comprehensive assessment that documents how NASA decided that its current plans are the best way to meet the agency’s long-term lunar exploration goals,” it stated in the report’s conclusion.

The person charged with keeping Artemis on track in some form for a 2024 launch is Doug Loverro, who started work in early December as the new associate administrator for human exploration and operations. Loverro spent his career in national security space, but explained in an interview last month that he had been interested in human spaceflight since his childhood.

“How can anybody who cares anything about space not go ahead and jump at the opportunity to put women and men back on the Moon?” he said, calling the job “the dream of a lifetime.”

Loverro said he’s still spending time getting up to speed on the various programs in his portfolio. “The way I learn how an organization works is you go out and meet people, and that's what I’m doing right now,” he said. “We will not get to the moon successfully unless we can look ourselves in the mirror and tell ourselves the truth about where we are, what we’re doing, what our issues are and what strong actions we need to take to solve them.”

It will be a few months, he said, before he weighs in on things like a launch date for the first SLS mission, Artemis 1, although it’s widely expected to slip from late 2020 to some time in 2021 (see “A work in progress”, The Space Review, December 16, 2019). He’ll also be busy with things outside of Artemis, like planning for commercial crew test flights and ensuring a US presence is maintained on the International Space Station.

Artemis, though, is clearly at the forefront of his mind. Since he started work at NASA, he has been wearing a lapel pin with the number of days until December 31, 2024, a reminder of the focus that he believes everyone involved in the program should have. “It’s a celebration of, ‘What are you going to do today to help us get closer to our goal?’” he said. “What did each of the individuals working on this program — not just senior officials like myself or the administrator or my program managers, but everybody in the chain—do today to go ahead and get us one step closer to the Moon?”

And there are a lot of steps to go before astronauts make their own steps on the Moon.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.