Target Moscow (part 2): The American Space Shuttle and the decision to build the Soviet Buranby Bart Hendrickx and Dwayne A. Day

|

| Now that the shuttle has been retired for nearly nine years after flying more than 130 missions, we have a good understanding of what the shuttle did. But it looked very different before it was flying, especially to those who lived on the other side of the Iron Curtain. |

Unfortunately, the authors did not explore alternative explanations for many of the facts that they observed, and when faced with two or more possible interpretations of the data, they chose the one that represented a worst-case scenario for their country. There was substantial public information in the United States on why NASA was developing a shuttle, what it would do, and its civilian management. Many of its justifications, such as supporting American jobs in California, were entirely domestic, not international.

There is another old saying that when you hear hooves, think horses, not zebras. When Okhotsimsky and Sikharulidze wrote their report, NASA had existed for 18 years as a civilian space agency. In fact, it had been explicitly established to conduct civilian, not military, missions. Despite tremendous evidence to the contrary, the two men viewed the space shuttle through a lens of paranoia and mistrust, and concluded that it was a weapon system with very little civilian utility.

Now that the shuttle has been retired for nearly nine years after flying more than 130 missions, we have a good understanding of what the shuttle did. But it looked very different before it was flying, especially to those who lived on the other side of the Iron Curtain. What is also clear is that the misinterpretation did not end with these two men. There is a legacy for their report that is equally filled with poor assumptions.

The Buran decision

Over the years it became popular belief that the study by the Institute of Applied Mathematics (Russian acronym: IPM) directly led to the decision to build Buran, the Soviet version of the shuttle, which was carried aloft by a heavy-lift launch vehicle called Energiya. The claim that the study triggered the Buran decision was made by several veterans of the Soviet space program and taken for granted in many journalistic accounts of Buran’s origins. Even Pavel Shubin, the researcher who recently published the 1976 study, seems to share that belief in his analysis, saying the study had “a very big influence on the Soviet space program.” The person he quotes to support that idea is Boris Gubanov, who for many years was the chief designer of the Energiya-Buran system. In his memoirs, published in 1998, Gubanov wrote:

On the basis of the [study], [IPM director and President of the Soviet Academy of Sciences] M[stislav]V. Keldysh sent a report to the Central Committee of the Communist Party, as a result of which [Soviet leader] L[eonid] I. Brezhnev, actively supported by [Central Committee Secretary for Defense Matters] D[mitri] F. Ustinov, took the decision to work out a set of alternative measures to guarantee the safety of the country.

What has been overlooked is that Keldysh put his signature under the report on March 24, 1976, which was more than a month after the official approval of the Buran project. That go-ahead came in the form of a decree issued by the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party and the Council of Ministers of the USSR on February 17, 1976. Locked away in archives for almost 30 years, the decree was finally declassified and published in a Russian book on the Buran project in 2004. It leaves little doubt that Buran was indeed primarily seen as a response to the perceived military threat posed by the American space shuttle, even though the shuttle is not mentioned by name. The objectives of the Buran project were literally described as follows:

- to counteract the measures taken by the likely adversary to expand the use of space for military purposes

- to solve purposeful tasks in the interests of defense, the national economy and science

- to carry out military and applications research and experiments in space to support the development of space battle systems using weapons based on known and new physical principles

- to put into near-Earth orbits, service in these orbits and return to Earth space vehicles for different purposes, to deliver to space stations cosmonauts and cargo and to return them back to Earth…

Underscoring the military motives behind the development of the Soviet shuttle, the decree tasked the Ministry of Defence with determining the system’s technical specifications. Although the design of Buran had not yet been frozen by that time, the decree did stipulate that it should be capable of launching and returning payloads of 30 and 20 tons respectively, closely matching the payload capacity of the US shuttle.

The first page of the February 17, 1976 decree that sanctioned the development of the Soviet space shuttle. (credit: NPP OmV-Luch publishers) |

Judging from the documents released by Shubin, an initial version of the IPM report was printed on February 26, 1976, nine days after the decree was passed. It then took almost another month for it to be approved by Keldysh, following which about two dozen copies of the report were disseminated to various organizations between March 1976 and February 1977. Therefore, contrary to popular belief, it could not have had an impact on the Buran decision.

The IPM study’s true significance

Sikharulidze gave some more background on the 1976 study in his memoirs, published in 2017. It resulted from research on the space shuttle that had begun at IPM more than a year earlier. The initiative for that had come from Okhotsimsky (a department head at IPM), who approached Sikharulidze in early 1975 with a proposal to analyze the possible uses of the shuttle. When the institute’s director, Mstislav Keldysh, was told about the idea at a subsequent meeting, he expressed doubt that one person would be up to that task, considering the fact that “tens of thousands of people at the organizations of Sergei Korolev and Yuri Mozzhorin” had been trying in vain to figure out the shuttle’s objectives. Keldysh was referring to NPO Energiya, the design bureau originally known as OKB-1 that was led by Sergei Korolev until his death in 1966 (it is now called RKK Energiya); and the Central Scientific Research Institute of Machine Building (TsNIIMash), the country’s leading space R&D institute, headed by Yuri Mozzhorin from 1961 until 1990.

| At the end of the meeting Keldysh reportedly said, “Maybe [the Americans] truly believe that we won’t be able to figure out the purpose of the space shuttle, but now that we have, we can use our diplomatic channels. Whenever their orbiter appears over our [territory], we can declare that we consider this an act of aggression and that we will use our own assets in response.” |

As Sikharulidze relates it, Keldysh’s skepticism did not discourage them, but, on the contrary, served as an extra motivation for them to get down to work. Judging from his account, he did the bulk of the work, with Okhotsimsky having only a supervising role. There are no indications that Sikharulidze focused on the possible military applications of the shuttle from the very outset. One of the references given in the 1976 report is another IPM study on the Space Shuttle written in 1975 by Sikharulidze and a fellow researcher, Raisa K. Kazakova. This appears to have been a general study of the shuttle and its capabilities rather than an analysis of its possible objectives (and there may have been even more such studies by IPM.) Presumably, it took several months of fact finding and research before Sikharulidze arrived at his conclusions.

Sikharulidze explains how it gradually became apparent to him that the shuttle only offered advantages over other space transportation systems during the atmospheric portion of its flight. This eventually led him to “the natural conclusion” that the shuttle was primarily designed to have a first-strike capability after launching from Vandenberg Air Force Base. After performing a single orbit, the orbiter would make a quick dive into the atmosphere, drop a nuclear bomb on Moscow and then boost itself back out of the atmosphere before initiating its final descent to Vandenberg.

The fact that Sikharulidze was so fixated on the reentry portion of the shuttle’s flight may have had to do with his own expertise in the field. After joining IPM in 1968, he had helped devise reentry profiles for Soviet piloted spacecraft returning from the Moon and in the early 1970s he co-authored several theoretical papers on atmospheric reentry together with Okhotsimsky. Perhaps not coincidentally, the double reentry technique that Sikharulidze came up with to allow the shuttle to carry out its bombing mission bore a certain resemblance to the reentry profile that the Russians had adopted for their lunar missions in the late 1960s (although these, of course, came back at much higher speeds.) This was a so-called double-skip reentry, in which the capsule bounced out of the atmosphere like a stone skipping across the water before beginning its final descent. It was the only way for Soviet lunar missions to return to Soviet territory and keep peak heating and g-forces within acceptable limits. The technique was successfully demonstrated by the unmanned Zond-6 and Zond-7 circumlunar spacecraft in November 1968 and August 1969.

Sikharulidze describes how he, Okhotsimsky, and two other IPM researchers briefed Keldysh on the results of the study, which must have been in late March 1976. Not being very eager to come to the meeting, Keldysh had set aside only half an hour for it, but ended up talking with the men for 2.5 hours as he became increasingly convinced that the conclusions were correct. At the end of the meeting Keldysh reportedly said, “Maybe [the Americans] truly believe that we won’t be able to figure out the purpose of the space shuttle, but now that we have, we can use our diplomatic channels. Whenever their orbiter appears over our [territory], we can declare that we consider this an act of aggression and that we will use our own assets in response.” He added about a dozen names to the proposed list of recipients of the report, “all of them on the highest government level,” as Sikharulidze puts it.

The study sparked mixed reactions, although most were positive. Two influential persons who supported its findings were Georgi A. Tyulin, the Deputy Minister of General Machine Building (the ministry oversaw the Soviet space and missile industry), and Andrei G. Karas, the head of the Chief Directorate of Space Assets (GUKOS), the forerunner of the later Military Space Forces. An utterly negative reaction came from Gleb E. Lozino-Lozinsky, who shortly after the February 1976 decree had been placed in charge of a newly established design bureau called NPO Molniya that would design and build Buran’s airframe. When Okhotsimsky, Sikharulidze, and another IPM scientist, Efraim Akim, presented the report to him, he bluntly called it “nonsense.” Lozino-Lozinsky was no newcomer to the field. About a decade earlier he had become the chief designer of a small air-launched spaceplane called Spiral (which never flew into space) and he may have had a better understanding of the shuttle’s true capabilities than anyone else in the Soviet space community at the time.

In his 2017 memoir, Sikharulidze discussed the impact that the report had:

Once approved by M.V. Keldysh, the report was sent to all the addresses agreed upon and it had a bombshell effect. After Keldysh reported to the Defense Council what kind of threat the space shuttle system could pose, the need was confirmed to develop the analogous Energiya-Buran system.

Set up in 1955 under Nikita Khrushchev, the Defense Council made decisions on key national security issues and was chaired by the General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party, who at the time was Leonid Brezhnev. Elsewhere in his memoirs, Sikharulidze repeats the later claim of Energiya-Buran chief designer Boris Gubanov that the report directly led to Brezhnev’s order to “work out a set of alternative measures to guarantee the safety of the country.” He also wrote that in September 1978 he was summoned to the headquarters of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, where he was praised for his argumentation in the report, but told that it did contain some “discussion points” After this he wrote what appears to have been an updated one-and-a-half-page summary of it for Brezhnev. It is not absolutely clear if he is referring to the 1976 report (this passage is elsewhere in the narrative), but, if he is, it is strange that this happened two and a half years after its release.

| While Sikharulidze and Akim do not explicitly state that the report directly led to the Buran decision, they do seem to imply that it did. Either by intention or ignorance, neither of them mentions the February 1976 Buran decree that preceded the report. |

Despite the benefit of 40 years of hindsight, Sikharulidze does not appear to have any second thoughts about the conclusions he formulated in the report. He even seems to believe an outlandish assertion made by space program veteran Vyacheslav Filin that the shuttle actually performed a “dive over Moscow” during one of its missions. Filin, who was a deputy chief designer of the Energiya rocket, first made this totally unsubstantiated claim in an interview in 1998 and has reiterated it several times since, most recently in an interview published in November 2018. Although the shuttle never flew from Vandenberg, Sikharulidze notes that it still could have made such a maneuver when returning from a mission in a 57-degree inclination orbit launched from the Kennedy Space Center. He does admit that such missions would have lost their surprise effect because the orbiter would not have been able to return to Earth after the first orbit and, instead of approaching Moscow from the south, would have had to overfly the entire country from east to west, giving Russian early warning systems ample time to detect it. For some reason, he singles out three shuttle missions that flew in 57-degree inclination orbits (STS-64, 68 and 99), but without specifically linking any of those to the alleged “dive over Moscow” (there were actually 20 shuttle missions that used this inclination.) Filin has usually referred to a mission in 1985, but has never specified which one.

Efraim Akim, one of the IPM scientists who took part in promoting the report in the weeks following its release, later did voice some reservations over its conclusions, but, like Sikharulidze, remained convinced of its significance. This is how he looked back at it in 1997:

When we learned of the decision to build a shuttle launch facility at Vandenberg for military purposes, we noted that the trajectories from Vandenberg allowed an overflight of the main centers of the USSR on the first orbit … When we analyzed the trajectories from Vandenberg, we saw that it was possible for any military payload to re-enter from orbit in three and a half minutes to the main centers of the USSR, a much shorter time than [a submarine-launched ballistic missile] could make possible (ten minutes from off the coast). You might feel that this is ridiculous but you must understand how our leadership, provided with that information, would react. Scientists have a different psychology than the military. The military, very sensitive to the variety of possible means of delivering the first strike, suspecting that a first-strike capability might be the Vandenberg Shuttle’s objective, and knowing that a first strike would be decisive in a war, responded predictably.

While Sikharulidze and Akim do not explicitly state that the report directly led to the Buran decision, they do seem to imply that it did. Either by intention or ignorance, neither of them mentions the February 1976 Buran decree that preceded the report. One can only assume that they tried to embellish the significance of the report or that their perception of it became clouded by stories they heard about it later. None of the space program veterans who told those stories are known to have been directly involved in the Buran decision-making process. Boris Gubanov, the man often cited in this respect, was not appointed chief designer of Energiya-Buran until 1982, six years after the project was approved. One person who did take part in many high-level meetings leading up to the Buran decision was Emil Popov, a member of the Military Industrial Commission (VPK), a body under the Soviet Council of Ministers that made key decisions on the development of military and space technology. Speaking in an interview with Bart Hendrickx in 2005, he denied that the IPM study had played any role in the decision to go ahead with Buran.

Despite this, it is entirely possible that people like Ustinov and Brezhnev were briefed about the report by Keldysh. After all, Keldysh was not only head of IPM, but also President of the Academy of Sciences and, in that capacity, had been a very influential figure in the Soviet space program since the early 1960s. Available accounts suggest that he was a strong supporter of the Buran program, which may seem strange given his background as a scientist. However, Keldysh had always been keen on putting his mathematical talents to practical use, making major contributions to a variety of strategic programs over the years. His appointment to the post of President of the Academy of Sciences was widely seen as symbolizing the marriage of the Academy as the headquarters of fundamental science to the military-industrial complex.

Mstislav Keldysh |

Still, even if the report made it all the way to the Kremlin, all it could have done at that stage was to strengthen the Soviet leadership’s conviction that it had chosen the right path by approving Buran only weeks earlier. As space historian Asif Siddiqi puts it in an email to the authors, “It’s the kind of report that could be circulated among high Party functionaries to justify a serious commitment even though a decision had been made. In other words, it didn’t lead to the decision on Buran, it was designed to fortify commitment to it now that the decision had been made.”

| Even if the report made it all the way to the Kremlin, all it could have done at that stage was to strengthen the Soviet leadership’s conviction that it had chosen the right path by approving Buran only weeks earlier. |

But how exactly the Kremlin responded to the report (if at all) remains open to speculation. Did it release additional funding for Buran? If it believed that Moscow was actually vulnerable to a shuttle sneak attack, did it seek to decrease that vulnerability by dispersing or hardening command and control centers? Or did Kremlin leaders order further intelligence collection and analysis about the American shuttle to confirm or deny the suspicions raised by the two mathematicians at one of their most prestigious institutes?

One effect the report did have was that IPM was given a more prominent role in Buran than in earlier space projects it had been involved in. As Sikharulidze recounts in his memoirs, the institute was assigned to work out trajectories for reentry, landing, and launch emergencies such as a return-to-launch-site abort and also to assist in developing software for the on-board computers and launch infrastructure, study the ignition of engines in weightless conditions, and so on.

Sikharulidze was also tasked by Keldysh with keeping close track of all the Western literature on the shuttle. One publication that stuck in his memory was an article in the November 1976 edition of Aerospace Daily which discussed a proposal by McDonnell Douglas to use the shuttle to drop experimental nuclear warheads on a test range in Poker Flat, Alaska (“on approximately the same latitude as Moscow”).

In addition to that, Okhotsimsky and Sikharulidze became two out of only three persons to represent the Academy of Sciences in the Interdepartmental Coordinating Council (MVKS), the leading body overseeing the Energiya-Buran program. This is another indication that Keldysh had been impressed with their work. The council included representatives of all the ministries involved in the program, all the chief designers as well as the heads of the main manufacturing facilities. During its regular meetings, usually held at the Baikonur Cosmodrome, it made key decisions on the technical and organizational aspects of the program.

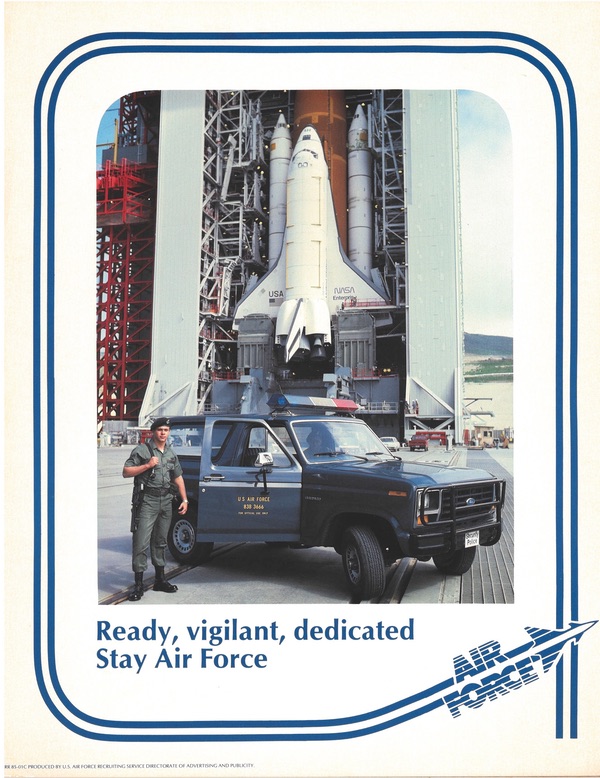

Air Force motivational poster produced when the shuttle Enterprise was used for fit-checks at Space Launch Complex-6 at Vandenberg Air Force Base. (credit: Roger Guillemette Collection) |

Buran’s murky origins

So, if it wasn’t the IPM study, what did lead the Russians to conclude that the American Space Shuttle presented a military threat serious enough to develop a counterpart? First, it was public knowledge by the mid-1970s that the Pentagon would become an important customer for the shuttle. Somehow, Cold War paranoia then lured the Russians into believing that military missions were the shuttle’s main goal, rather than a secondary goal. What may have contributed to this was the still scattered nature of the information openly available on the shuttle at the time. While the origins and objectives of the shuttle program may be obvious in retrospect, they may have been much less so in the early and mid-1970s, certainly from the Russian vantage point. As Asif Siddiqi puts it, the Russians may well have been misled by “a lack of coherence in the US media about a particular narrative around the origins of the Shuttle in the mid-1970s” and “the general garbled nature of information as it made its way from the U.S. to the USSR through erroneous translations, etc.” What may have further fueled the Russians’ mistrust was the absence of a clear dichotomy between military and civilian projects in their own space program, which lacked a civilian space agency like NASA.

Second, several other Soviet research institutes are known to have begun studies on the shuttle not long after the program was sanctioned by President Nixon in early 1972. At least one of those institutes, TsNIIMash, also viewed the proclaimed cost benefits of the space shuttle as a cover story for its military objectives. Yuri Mozzhorin, who headed TsNIIMash at the time, recalled in a 1995 interview:

[The Space Shuttle] was announced as a national program, aimed at 60 launches per year … All this was very unusual: the mass they had been putting into orbit with their expendable rockets hadn’t even reached 150 tons per year, and now they were planning to launch 1,770 tons per year. Nothing was being returned from space and now they were planning to bring down 820 tons per year. This was not simply a program to lower transportation costs (they promised they would lower those costs tenfold, but the studies done at our institute showed that in actual fact there would be no cost savings at all). It clearly had a focused military goal.

Unlike their colleagues at IPM, the TsNIIMash researchers did not have bombing missions in mind. According to Mozzhorin, the shuttle’s 29-ton payload-to-orbit capacity and, more significantly, its 14-ton payload return capacity, were seen as a clear indication that one of its main objectives would be to place massive experimental laser and particle beam weapons into orbit that could destroy enemy missiles from a distance of several thousands of kilometers. The reasoning behind that was that such weapons could only be effectively tested in actual space conditions and that in order to cut their development time and save costs it would be necessary to regularly bring them back to Earth for modifications and fine-tuning.

| Whereas the Soviets were concerned that the shuttle could be used as a weapon, American defense officials were aware that it could be misinterpreted as such. |

True, it is not clear when exactly TsNIIMash made these studies, which obviously is crucial to assess their possible influence on the Buran decision. What is known is that, in June 1974, TsNIIMash and five other research institutes finished a joint study of the Soviet Union’s future space transportation requirements to help determine the Soviet response to the space shuttle. It essentially concluded that from an economic standpoint it made little sense for the Soviet Union to develop a transportation system akin to the Space Shuttle. Still, based on available accounts, it would seem that the Soviet shuttle had taken center stage in future plans for the country’s piloted space program by the middle of 1975. Although it would gobble up a significant portion of the Soviet space budget for the next decade or so, it was apparently considered vital to maintain strategic parity with the United States. Ultimately, Buran made just one short uncrewed trip into space in November 1988 before it was canceled in 1992.

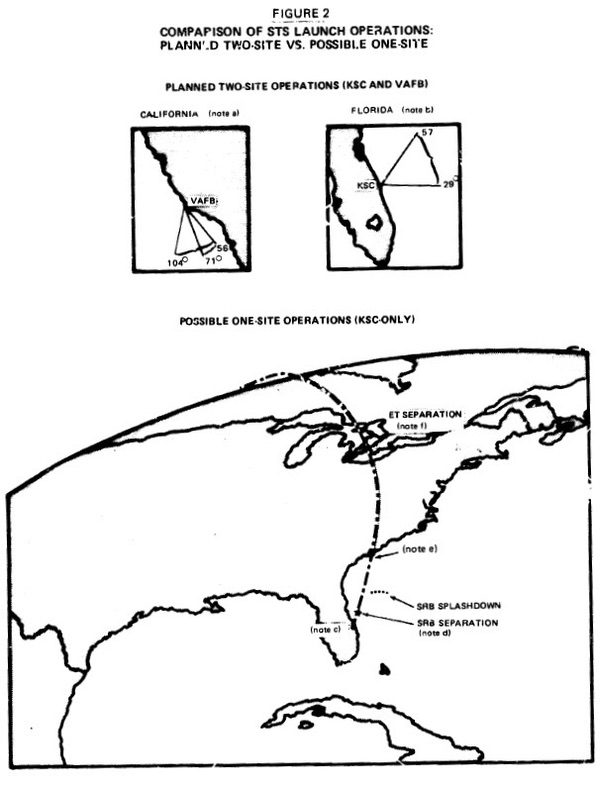

Whereas the Soviets were concerned that the shuttle could be used as a weapon, American defense officials were aware that it could be misinterpreted as such. In February 1978, Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering William J. Perry (who would later become Secretary of Defense in 1994) wrote a letter to the General Accounting Office (GAO) about a draft report they had produced. The GAO’s draft report recommended against a Vandenberg launch site for the shuttle on the assumption that DoD payloads could be launched out of Florida instead. Perry stated that the Department of Defense “strongly disagrees with your recommendation,” and offered a number of corrections to the report’s language on the military use of the shuttle, particularly concerning northern launches from Florida. Perry wrote “we cannot ignore the fact that northerly high inclination shuttle launches ascending over the Soviet Union, even with prior notification, will be disconcerting and perhaps objectionable to the Soviets. No matter how sophisticated the Soviet radars, the similarity of such northerly shuttle launches to potential U.S. ICBM launches can lead to adverse Soviet reactions, if done routinely. Under worst case conditions, such as a shuttle breakup during ascent, a severe Soviet response cannot be discounted.”

Although Perry’s comments were about Florida launches, presumably the Department of Defense was also aware that certain launches to the south from Vandenberg would also place the shuttle over Soviet territory with little advance warning. This was, of course, why some of the early shuttle mission scenarios involved polar launches that did not immediately cross over Soviet territory.

Illustration from a 1978 General Accounting Office (now Government Accountability Office) report on the need for a California launch site for the space shuttle. The GAO draft report recommended that Florida be used for all shuttle launches, including Department of Defense launches to polar orbit. A DoD official argued that it was not suitable, noting that launches over the North Pole could alarm the Soviet Union and make them think an attack was underway. (credit: GAO) |

A broader question that is probably impossible to answer at this time is how the Soviet intelligence establishment evaluated the Space Shuttle and American military space plans. Was the study by Sikharulidze and Okhotsimsky supported by evidence gathered by the KGB and GRU? Did they possess other intelligence data about possible shuttle payloads, such as the rumored experimental laser and particle beam weapon systems it might carry? Did the KGB and GRU analysts recognize the difference between the American military and civilian space programs and their respective communities and bureaucracies? Furthermore, how did Soviet intelligence assessments of the American space program influence senior Soviet leaders? Major government decisions are often based upon, or at least influenced by, data from multiple sources, including many that remain inaccessible four decades later.

Unfortunately, virtually all that is known about this episode of the Soviet space program is based on memoirs and biased histories of various organizations involved in the Buran project. Only when more primary documents from this period are declassified will it be possible for historians to more accurately reconstruct the true story behind the decision to build Buran. However, it does seem that the significance of the IPM study has been grossly overestimated. All it did was to reinforce conclusions that the Russians had already arrived at well before it was released.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.