Review: Fighting for Spaceby Jeff Foust

|

| Cobb testified that NASA should add women to the astronaut corps. Cochran also testified at the same hearing, but argued against a rushed effort like what Cobb sought, warning a crash program could be counterproductive. |

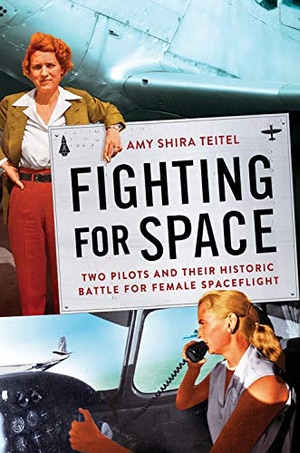

The new book Fighting for Space by Amy Shira Teitel profiles those two women and their efforts to get women—including themselves—into space in the early years of the Space Age. The book is, in essence, two biographies in one. Cochran grew up in a poor family in the South (she would, in adult life, hide that heritage, portraying herself as an orphan) who moved to New York, became a stylist to the rich and famous, and met a wealthy man who would eventually become her husband. An interest in flying became a passion and vocation, and in the 1930s Cochrane was one of the most famous pilots, male or female, winning air races and setting records. Her aviation and business connections opened doors across industry and government, and she became friends with people like Dwight Eisenhower and Lyndon Johnson.

Cobb, born a quarter-century after Cobb, had an interest in flying since being a child, but struggled to find work as a pilot: in post-World War II America, there was no shortage of former military pilots and a reticence to hire women pilots. She did find some work, and also managed to set some aviation records. At a conference in 1959, she had a chance meeting with Lovelace, who said he was interested in putting women pilots through the same medical tests that his clinic administered to the men seeking to become Mercury astronauts. Cobb later agreed to be Lovelace’s first test subject.

That set in motion the events, in many cases widely known from past historical accounts, in the second half of the book. When Lovelace presented his results, showing the Cobb passed the same medical tests that the Mercury astronauts did, she became famous, and other female pilots stepped forward, expressing their interest. Lovelace contacted Cochran for advice since she directed the Women’s Auxiliary Service Pilots program during World War II. Cochran was willing to help, and even provided financial support for the testing of more women, but was concerned about the publicity that often portrayed the testing as an official “women in space” program, as well as all the media attention that Cobb received.

Neither Cobb nor Cochran, though, could get NASA interested in opening up the astronaut corps to women. NASA administrator Jim Webb did name Cobb as a consultant to the agency “on the role of women in the national space programs” just days after Kennedy’s famous May 1961 speech, but that position did not get her the access or influence she expected. Lobbying Vice President Johnson also failed to get action for Cobb.

| Teitel said she didn’t correct or question some accounts in the main body of the text because they don’t affect the larger story “and I felt strongly about wanting to honor how these women saw themselves.” |

Matters came to a head in a July 1962 House hearing on the role of women in space, where Cobb testified that NASA should add women to the astronaut corps. Cochran also testified at the same hearing, but argued against a rushed effort like what Cobb sought, warning a crash program could be counterproductive. She thought women would fly in space some day, but was in no hurry to do so. While Cobb continued to lobby for flying women for a while after that hearing, it essentially marked the end of the efforts to fly any of those women.

Teitel certainly brings to life these two pioneering women who had similar visions, but conflicting views of how realize them. But there are some issues with the book. While Teitel emphasizes the research she did, including archives with Cochran’s extensive collection of papers (some of which are reproduced in the book), there are no footnotes to identify what sources she used at what points in the next. “To avoid having 1,216 footnotes, all sources are listed by chapter in the bibliography,” she writes in an author’s note at the end of the book, later saying she avoided footnotes “because I didn’t want to impact your experience meeting and reading about these women.” But there are ways other than footnotes in the chapter—endnotes, notes on sources, etc.—to more thoroughly cite sources and to make it easier for others to follow up on that work. (Teitel, as readers here may recall, plagiarized others’ works in some of her earlier articles; there’s no evidence, though, of that here.)

Teitel also acknowledges in that note that some of the things written about both Cobb and Cochran in the book might not be true. The book describes how Cochran witnessed the death of another pilot during an air race, but Teitel says in the note that Cochran was not, in fact, there to see the crash. The book states how Cobb, as a young pilot ferrying planes to South America, was imprisoned for 12 days in Ecuador, but Teitel says that while Cobb stated in her first memoir she was jailed for that long, in a later memoir she said she was freed after just two days.

Teitel said she didn’t correct or question those accounts in the main body of the text because they don’t affect the larger story “and I felt strongly about wanting to honor how these women saw themselves.” But a historian should want to honor what happened, and address inconsistencies in the text—and perhaps also see if they should question any other statements those people made. That’s what is needed to truly understand what took place, and the impact these women had on the early space program.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.