Review: Handprints on Hubbleby Jeff Foust

|

| Sullivan was completing her doctorate and thinking about her career plans when NASA announced its plans to recruit new astronauts in the mid-1970s. Seeing the Earth from space “seemed a more than fair exchange” for giving up an opportunity to dive to the ocean floor in submersibles. |

That scientific record and public support would not have been possible without a series of servicing missions to repair and upgrade the telescope. Five shuttle missions from 1993 through 2009 visited Hubble, repairing and replacing components and swapping out instruments, extending Hubble’s lifetime and improving its scientific capabilities. Those repairs, in turn, would not have been possible without careful planning prior to the mission’s launch to ensure that it could be serviced by spacewalking astronauts, working in weightlessness wearing bulky suits.

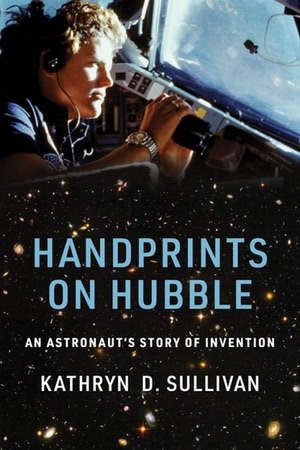

One key individual in that effort was NASA astronaut Kathryn Sullivan, the first American woman to walk in space. As part of the STS-31 crew, she trained for spacewalks along with Bruce McCandless in case anything went wrong with the spacecraft’s deployment. That work, though, also included efforts to make it easier for future missions to repair the telescope, an effort she describes in her book Handprints on Hubble.

The book starts off along the familiar lines of any astronaut memoir. Sullivan grew up interested in maps and travel, and though she would pursue a career in the Foreign Service. A college course in geology and oceanography led her to instead decide to become an oceanographer, and she was completing her doctorate and thinking about her career plans when NASA announced its plans to recruit new astronauts in the mid-1970s. Seeing the Earth from space “seemed a more than fair exchange” for giving up an opportunity to dive to the ocean floor in submersibles, and she applied, ultimately becoming one of six women in the famous 1978 astronaut class.

Sullivan got to fly in space on the STS-41G shuttle mission in 1984, performing a spacewalk to test satellite refueling technology with Dave Leestma. In early 1985, shortly after that successful mission, she was asked to join the crew of what was then designated STS-61J, the shuttle mission to deploy the Hubble Space Telescope then scheduled for August 1986.

The book shifts gears at this point, as Sullivan examines the history of Hubble’s development (Sullivan, a few years ago, spent a year as a fellow at the National Air and Space Museum, researching Hubble’s history.) NASA envisioned early in the mission’s development that the telescope would be serviced, but offered few specifics to contractors. “The sum and substance of its instructions on the maintenance boiled down to ‘It shall be maintainable,’” she writes of language in a 1977 request for proposals.

At that time, NASA expected that only modest maintenance would be done to Hubble while in orbit, with the telescope returned to Earth every several years for major work. By the early 1980s, though, the agency concluded that was infeasible, and thus planned to do all maintenance on the telescope in orbit.

Sullivan and McCandless, working with NASA and Lockheed engineers, focused first on the potential contingency repairs they might have to do on the deployment of Hubble. However, they also looked ahead to repairs needed on future missions, including the tools needed for that specialized work and what needed to be done before launch to ensure as many elements of the telescope as possible could be repaired in space.

The delay in Hubble’s launch caused by the Challenger accident gave Sullivan and McCandless an opportunity to advocate for changes in Hubble components to make it more serviceable, despite some objections from officials who didn’t want to make changes that might end up damaging the spacecraft. Sullivan describes in the book efforts like changes to a power control unit and creation of new tools as examples of that work that paid dividends on future servicing missions.

| “Every servicing mission team improved upon the existing methods and invented new devices to tackle ever more complex repairs, but all relied heavily on the tools and equipment produced by the original [maintenance and repair] team,” she writes. |

While Sullivan and McCandless trained for spacewalks to fix Hubble, neither got to do one, although at point they were nearly ready to do so. When one of Hubble’s two solar panels failed to deploy properly, they went to the shuttle’s airlock and put on their suits (with the assistance of fellow astronaut Charlie Bolden), expecting they would be called upon to go out and fix the panel. Controllers, though, were able to command the panel to fully deploy at last, and the two spacesuited astronauts, stuck in the airlock, missed seeing the release of Hubble from the shuttle’s robotic arm.

Neither astronaut would perform a Hubble repair spacewalk, as it turns out. McCandless left NASA after STS-31 and while Sullivan would fly another shuttle mission, STS-45, she was passed over to be the lead spacewalker on the first servicing mission, STS-61, in favor of Story Musgrave. “There was no arguing that Story was a great pick and very deserving of the assignment, but the new stung nonetheless,” she writes. She was already considering leaving the agency around that time, and in 1993 would so do when nominated to become chief scientist at NOAA. (She would return to NOAA during the Obama Administration, serving as administrator from 2014 to January 2017.)

“My split with Hubble was cold turkey,” she recalled, watching from outside the agency as the STS-61 crew successfully repaired the telescope. Her concerns were reinforced by the perceptions that the Goddard Space Flight Center personnel that had responsibility for the servicing mission didn’t initially welcome the experience and wisdom of the maintenance and repair (M&R) team from Hubble’s development, but, she writes, “Goddard’s disregard for the Lockheed team’s expertise soon wore off.”

The success of STS-61 enabled future, and more ambitious, servicing missions. “Every servicing mission team improved upon the existing methods and invented new devices to tackle ever more complex repairs, but all relied heavily on the tools and equipment produced by the original M&R team,” she writes. The astronauts on those servicing missions left literal handprints on Hubble, in the form of smudges the gloves of their suits left on the weathered exterior of the telescope. While Sullivan didn’t make any of those spacewalks, her handprints are also on Hubble in the work she did, with engineers and fellow astronauts, to make those repairs possible.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.