Wasn’t the future wonderful?For All Mankind and the space program we didn’t getby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The series began with a bold premise: what if only a few weeks before the planned Apollo 11 mission the Soviet Union landed a man on the Moon? |

Now Apple TV+ has turned that emotional connection to the Cold War space race into an alternative history television show, For All Mankind. The show, which aired its first season last fall and is currently filming its second season, is produced by Ronald D. Moore, Ben Nedivi, and Matt Wolpert. The first season consisted of ten episodes covering the period of roughly 1969 to 1975, with NASA establishing a rudimentary outpost at the Moon’s south pole, facing off against a similar station built by the Soviet Union. The second season will apparently pick up in the 1980s. For All Mankind is alternative history, also known as counterfactual history, a form of fiction most recently explored by the Amazon television show The Man in the High Castle. Alternative history has a mixed reputation among actual historians. For All Mankind has demonstrated that even in a fictional storytelling setting it can have value, and can be thought-provoking. But the show has also adopted a more romantic than realist approach to its subject, and that may be its weakness. In short, it depicts an alternative history with few apparent downsides.

Ronald Moore is no stranger to science fiction. He was a key writer on Star Trek: The Next Generation in the 1980s and involved in its spinoffs in the 1990s, until Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry’s utopian vision of the future became too constraining for the stories that Moore wanted to tell. He later produced the early 2000s series Battlestar Galactica, which, like the original Star Trek, used a science fiction setting to explore contemporary political issues, primarily the aftermath of 9/11 and the moral quagmire of the occupation of Iraq. In For All Mankind, Moore is using an alternative history of the space race to explore aspects of American social progress while at the same time indulging the fanboy’s fantasy that Apollo never ended. Moore has said that the show is intended to depict a world that leads to Star Trek. But Star Trek, until the past decade or so, was a positive vision of the future where humanity not only failed to blow itself up, but had rid itself of conflict and scarcity. For All Mankind, although depicting the kind of space program that many have daydreamed about, shows a darker world not of cooperation in space, but realpolitik competition.

Jodi Balfour as astronaut Ellen Waverly, one of America's first female astronauts. For All Mankind depicts an alternative history where the Apollo program continues and America selects women and minorities as astronauts a decade before it actually happened. The show poses fascinating questions about American history, politics, and social and cultural progress. (credit: Apple TV+) |

What if the Soviets were first on the Moon?

The series began with a bold premise: what if only a few weeks before the planned Apollo 11 mission the Soviet Union landed a man on the Moon? In reality, by 1969, the Soviet Union was years away from a successful Moon landing, due to myriad reasons, from an underfunded Moon program, inter-governmental squabbling, and limited technology. For All Mankind posits that the Soviets somehow made better choices and launched a rocket to the Moon without the CIA really knowing about it (a CIA official explains that they had delivered percentage estimates but the Soviets managed to beat the odds.) This Soviet feat is then followed by a near-disastrous Apollo 11 mission that revives American spirits, followed by another Soviet coup: the first woman on the Moon.

While providing a rationale for continuing the space race, that latter twist gives the show its other major theme: losing the race to the Moon may have caused NASA to continue with more space missions, but now the United States had to give women greater opportunities, including making them astronauts. The title For All Mankind starts to seem a bit ironic by the third episode as women take center stage in the space race.

The premise is thought-provoking and also informative. One of the criticisms by academics of counterfactual history is that it is merely fiction and lacks any explanatory value. Not everyone agrees on this point. Robert Cowley and Niall Ferguson have published anthologies of works by prominent historians positing what-if questions in history. Last year, Quest magazine devoted an entire issue to what-if questions in space history. Counterfactual scenarios may even have more practical applications. In 2017, insurance company Lloyd’s commissioned a study on counterfactual risk analysis to explore various scenarios where, if events had happened differently, there could have been profoundly different outcomes (imagine, for example, that instead of grounding on an island in 2012, the Italian cruise ship Costa Concordia had drifted a half kilometer farther and capsized, drowning thousands of passengers; the impact on the cruise ship industry would have been substantial). The purpose of the study was to explore Lloyd’s vulnerability to alternative events, particularly “near-misses.”

| One of the powerful lessons of For All Mankind is how the way things happened in real life is not necessarily how they had to happen. Change a few events and situations that we might consider impossible no longer look so impossible. |

For All Mankind’s writers have done a good job of demonstrating the value of counterfactuals beyond merely entertainment in several ways. One lesson that they teach is that events can be like billiard balls, ricocheting off other events in unexpected ways, and even rolling backwards. One of the clever observations by the show’s writers is that losing the Moon race would have raised questions about Apollo 10 and why it did not land when the lunar surface was so incredibly close. Was NASA too risk-averse after the Apollo 1 fire? Some people may have concluded that it was, and that bolder leaps were required. Some people also would have desired scapegoats. Another unexpected outcome could have been political, demonstrating the quirks of circumstance: instead of heading to Chappaquiddick Island right before the Apollo 11 landing, Ted Kennedy cancels that trip, Mary Jo Kopechne does not drown, and Kennedy’s political prospects survive; he eventually beats Nixon in the 1972 election.

What the show also indicates, however, is that even with different events, people remain mostly the same. Their characters do not change—Ted Kennedy might become president, but he’s still a philanderer; Nixon may lose, but he’s still a mean S.O.B. engaged in dirty tricks.

One larger issue not fully addressed by the show is how the Soviets reaching the Moon first would have affected America’s standing in the world. When Apollo 11 landed on the Moon it resonated around the world in part because the United States, for all of its flaws, still had wide appeal, not only for its economy and culture, but a reputation for welcoming immigrants and the attitude that anybody could become a citizen and pursue the “American dream” of success. Thus, somewhat ironically, when an American walked on the Moon, many people around the world felt that it was a human achievement rather than a uniquely American one. If that person had been a Soviet cosmonaut, however, would that have been as appealing to non-Americans and people not within the Soviet sphere of influence? There’s a throwaway line in an episode about teenagers wearing hammer and sickle logos in London, but no effort to explore the larger cultural impact of losing the Moon race to the Soviet Union.

Shantel VanSanten, as Karen Baldwin, who starts to question the tightly-wound life she has led, and develops an unexpected friendship with another astronaut's spouse. (credit: Apple TV+) |

A better world

One of the powerful lessons of For All Mankind is how the way things happened in real life is not necessarily how they had to happen. Change a few events and situations that we might consider impossible no longer look so impossible. The best example, and one that is a main thrust of the show’s narrative, is the aforementioned introduction of women to the astronaut corps.

NASA did not incorporate women into the astronaut corps until the late 1970s and did not launch them into space until the early 1980s. It was not until 1998—a full 20 years after they were allowed to become astronauts—that the first woman commanded a NASA space mission. What For All Mankind posits—no, argues—is that there is no reason why this social progress could not have happened sooner with the right push by political leaders. A tired argument is that because astronauts in the 1960s had to be military test pilots—and there were no women test pilots—it was impossible for women to become astronauts. But Harrison Schmitt and his fellow scientist astronauts were not military test pilots and were introduced to the program because of political pressure. The same lesson can be applied to minorities as well. If instead of congressional pressure to put a scientist on the last Apollo mission, the pressure had been to put a minority or woman in the program, Gene Cernan’s partner on Apollo 17 could have been black, or female. It was not impossible to have women or minority astronauts earlier than we did. Rather, it was a choice.

To its credit, the show acknowledges that introducing women so early and quickly into the space program would not have gone smoothly, not because of sexism (which still exists in the show), but because the women inducted into the astronaut corps lacked the flight training and experience of their male colleagues and had a steep learning curve to climb. At one point, two male astronauts identified only as Grush and Pendle grumble about the new situation, with one of them asking “You wanna explain to me how I flew two Gemini missions and now I’m backing up a chick, a geezer, and a Korean? Remember how it used to be about merit around here?” The show also indicates that not all women would have been supportive of women astronauts. One astronaut’s wife is hostile to the idea, believing it to be an insult to all that her husband has worked for, not to mention her own sacrifices in support of his career. One of the show’s greatest strengths is the sophistication of its cultural world-building, exploring what would change and what would stay the same, and how prejudices, biases, and institutions endure.

| The “what if” question is a particularly powerful one for space enthusiasts of a certain age, and there may be fine gradations of differences. The age of the dreamer is important in determining what they dream. |

Perhaps the show’s greater leap is that it depicts a NASA much more willing to take risks than it was already taking. People die in space—famous people. Missions go awry, and commanders and Mission Control have to make hard choices that sometimes go terribly wrong, and sometimes they barely manage to rescue survival from the jaws of destruction. Politicians may gripe and threaten NASA administrators, but they are still willing to support the obviously very expensive space program even when it may hurt them politically. In actuality, the Apollo 1 fire caused a lot of second-guessing in Congress, and we now know that Richard Nixon nearly canceled the later Apollo missions after Apollo 13 because he was so scared of another disaster. (See John Logsdon’s excellent “After Apollo?” book for details of just how bad things got.) Even some NASA officials wanted to declare victory after the first few Apollo missions and halt the program. Many of the people who were most responsible for the program were eager for it to come to an end before somebody got killed.

Apollo’s orphans

The “what if” question is a particularly powerful one for space enthusiasts of a certain age, and there may be fine gradations of differences. The age of the dreamer is important in determining what they dream. Ronald Moore was six when Apollo 13 nearly killed its crew and the astronauts returned home to a relieved nation. Kids at that time watched black and white television footage of actual events, and then were blown away when 2001: A Space Odyssey filled the big screen in 1968 with visions of a squeaky-clean nuclear-powered future where giant wheels rotated in the sky. For these people there was an extraordinary sense, first of a future coming, and very soon after, that of having it yanked away.

If you were a kid back then—for girls it was harder to see themselves as astronauts in that future—you probably did not understand the geopolitics. You probably did not even realize that by the time Neil and Buzz walked on the Moon, the Saturn V was already out of production. You may have seen books and magazine articles with artwork about sending humans to Mars and never realized that at that very moment people in Nixon’s White House were considering eliminating human spaceflight entirely, and even getting rid of NASA itself to save money. Even adults would have been surprised by the vast gulf between what was happening in public—NASA Administrator Tom Paine was talking about trips to Mars—and the sobering reality.

Why does this era resonate among certain people? The excitement of space exploration was certainly very real during the 1960s, but it did not come out of nowhere. When John F. Kennedy announced the goal of sending humans to the Moon, he set it within his larger overall philosophical framework. Kennedy had run on a platform with deep roots in American mythology, the idea of the frontier as new territory to be explored, conquered, and then settled. Kennedy’s “New Frontier” rhetoric fit easily into the concept of space as a new frontier: not simply territory, but challenges that brought out the best in people and institutions. As Kennedy said it, we do these things not because they are easy, but because they are hard, and because doing them makes us better human beings. And indeed, when you really think about it, the space race and what it came to represent to a certain generation of Americans is actually not that unique. It is really an extension of a cultural undercurrent percolating through American society since the creation of the country. There were people who wanted new frontiers and new challenges long before there was a space program, there are people who want them today, but in different types of endeavors. We don’t have to colonize Mars to achieve those emotional, philosophical and psychological goals, but some people believe that it is the best way.

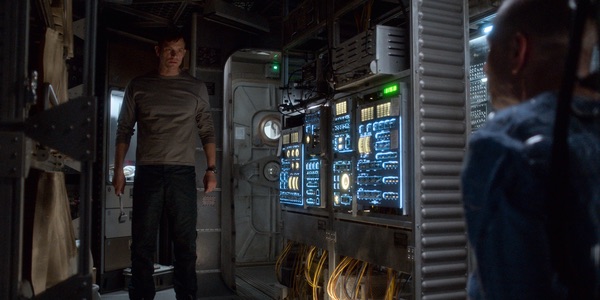

Joel Kinnaman as astronaut Edward Baldwin, at the Jamestown moonbase. The show posits an alternative future where the Apollo program continued. (credit: Apple TV+) |

Counterfactuals’ risk

For All Mankind is feeding that mentality, the view that this is what should have happened. But to what extent is this intellectual laziness? The show is in some ways liberal self-indulgence—not only did the space program continue and America got a lunar base and cooler rockets, but social progress also took a lurch forward, with America launching female and minority astronauts (and even a lesbian) into space, and even making them mission commanders, years before any of this actually happened. In this alternative history the Equal Rights Amendment is passed in the early 1970s due in part to some back-room political horse-trading involving Apollo contracts. Nixon ends the Vietnam War early and is also restricted to only one term (although the viper has not been totally de-fanged.) The show hints—but does not really declare—that détente with China and then the Soviet Union did not happen in this alternative timeline. For the most part, it’s a liberal vision of a better America.

| For All Mankind is feeding that mentality, the view that this is what should have happened. But to what extent is this intellectual laziness? |

But what are the downsides of continuing the space race? The show hasn’t really depicted any. However, if Apollo had continued and spent even more money, that money would have had to come from somewhere. Did it come out of domestic programs? Did a more progressive America get the ERA and female astronauts and even a black woman on the Moon but then see Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society programs gutted to pay for it? Instead of the Apollo-Soyuz handshake in space we get a superpower standoff on the Moon. Would continuing the space race and extending superpower competition to the lunar surface have also made the Cold War hotter? Maybe Vietnam ended, but Central America boiled over even sooner than it happened in reality.

So far, the show has not explored this issue in any depth, perhaps because it is a murky one little studied or understood in our reality. The 1975 Apollo-Soyuz handshake in space did not prevent the Soviets from invading Afghanistan four years later. It is unclear that twenty years of US-Russian cooperation on the International Space Station has had any effect on how the two countries relate to each other in foreign policy. If the space race had continued as shown in For All Mankind, is there any reason to believe that international relations would have changed in any significant way?

This leads to a more direct question: what would this continued space race have done to the space program itself? Would it have cost anything? Anything we would have regretted?

In 1996, Stephen Baxter published Voyage, a novel depicting an alternative history where John F. Kennedy survives assassination and the Apollo program continues and transforms, with NASA eventually sending astronauts to Mars. But unlike For All Mankind, in Voyage the space agency pays a price. Its space science program is wiped out. There is no Viking program, no Pioneer Venus, no Pioneers 10 and 11 or Voyagers 1 and 2 to the outer solar system, and no Hubble Space Telescope. Humans walk on Mars, but they know far less about their own solar system, or the mind-boggling universe around them. Would space enthusiasts have found that price acceptable? Considering that for many enthusiasts their excitement and interest primarily extend to human spaceflight, if not outright astronaut worship, and nothing more, the answer is probably yes. But we would have had no Carl Sagan, no Pillars of Creation, no volcanoes on Io, geysers on Enceladus and Triton, or oceans under the surface of Europa. The sheer wonder of the universe would have been, well, less wondrous.

For All Mankind is the romanticized counterfactual myth, whereas Baxter’s Voyage is the realist counterfactual myth. The danger of the romanticized counterfactual myth is that it perpetuates belief in things that just aren’t true. Facing the reality head-on has more value, because it forces us to do so when we think about current events and current choices. But the romanticized myth can still be enlightening, because it can show that we’re not prisoners of our biases and our prejudices and we can rise above them. Consider again the situation involving women astronauts in the space program by the early 1970s. By arguing that it was impossible, that it could not happen, we are conceding that American society was too sexist to allow it to happen. By showing a set of events that could allow it to happen, the show is making a case that America can make social progress.

Space ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids

All this discussion of the politics and the policies and the programmatic tradeoffs of a fantasy space program may create the impression that For All Mankind is only (merely?) about those things. It’s not. It is also about the humans who do all these things. There is the workaholic female engineer in Mission Control who breaks the glass ceiling by blackmailing her boss, the uptight astronaut wife who forms a touching and enriching friendship with the pot-smoking artist husband of another astronaut, the freewheeling flyboy who nearly goes insane, and the stoic commander who realizes way too late that the compartments he has erected in his life to be successful at his job have walled him off from his family, with tragic results. Perhaps those stories will be the subject of another article. They form the emotional core of the show.

| So far, the show has depicted living on the Moon as lonely, boring, psychologically damaging, dangerous, and just plain hard—with no apparent upside, unless the coolness factor of a moonbase is its own reward. |

By the halfway mark of the first season, the focus of the show shifted to the first lunar outpost, a “settlement” called Jamestown on the edge of a crater at the Moon’s south pole where water ice has been found. The Soviet Union has also set up their own outpost, and the two groups eye each other from a distance—or so the Americans think at first. The purpose of these two rudimentary bases is unclear even to the participants. An American general is keenly concerned that the Soviets may be seeking military advantage, although nobody has figured out what the military advantage of a moonbase is even after it has been there for a year. What is clear is that countries are spending a lot of money to support their fragile facilities on the lunar surface, without really understanding why.

What the show also demonstrates is that even achieving the dream of an expanded human space exploration program is not necessarily all that great—and the path from there to Star Trek may be a lot more impossible than we can imagine. By the end of the first season, America has launched Apollo 25, and a post-credits scene jumps to 1983 when the United States is building even bigger rockets in pursuit of bigger ambitions.

The farther away the show gets in time from what actually happened in real life, the less value it will have as a counterfactual thought experiment. But so far, the show has depicted living on the Moon as lonely, boring, psychologically damaging, dangerous, and just plain hard—with no apparent upside, unless the coolness factor of a moonbase is its own reward. For All Mankind may have embraced the utopian space enthusiast ideal of continuing human space exploration beyond low Earth orbit, but it also illustrates a sobering reality, that if you ask the question “what if?” any answer may be unsatisfying.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.