Another look at The Vinyl Frontierby Glen E. Swanson

|

| During an age when analog recordings were still king, a team led by six individuals sent a very sophisticated LP into space with hopes that someday, somewhere, another life form smart enough to find it would be presented with a record—literally—of who we are. |

In the more than 40 years since the two spacecraft left Earth, much has been written about the twin Voyagers. Even though both spacecraft are now hurtling out beyond the solar system, their useful science mostly done, one onboard experiment holds an enduring fascination because its mission still has the possibility, though remote, of being fulfilled.

On the eve of the 100th anniversary of the premiere of Thomas Edison’s phonograph, a small group of people managed to put together the ultimate message in a bottle. During an age when analog recordings were still king, a team led by six individuals sent a very sophisticated LP into space with hopes that someday, somewhere, another life form smart enough to find it would be presented with a record—literally—of who we are.

The story of this pair of identical two-sided 12-inch gold-plated copper LPs containing both the sights and sounds of humanity along with a sampling of Earth’s greatest hits including “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry, has been told before. In 1978, the book Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record gave the most comprehensive overview of the record’s development as told by the original team members who produced it. In 2017, PBS produced the documentary The Farthest about the Voyager project. Around that same time, a highly successful Kickstarter campaign produced a set of LP records containing newly re-mastered recordings of the original Voyager record contents.

With all of this relatively recent attention to the Voyager records, could anything new be added to the story?

Even though Jonathan Scott, the author of The Vinyl Frontier, heavily relies on secondary sources for much of his reference material, he still manages to pull off a surprisingly insightful narrative supported in part by a generous use of non-published materials provided to him by many of the team players that assembled the original Voyager record.

Jonathan Scott was born a year before both spacecraft were launched. While Voyager 1 left Saturn and the solar system, Voyager 2 later continued on to Uranus and Neptune. It was during this time that a teenage Scott could be found listening to music on his Sony Walkman.

Scott grew to not only love music but also to follow these later Voyager flybys. It was through his interest in music, however, that he found his true calling, writing for Record Collector magazine and editing books about Prince and Cher. The author’s musical background combined with his interest in the Voyagers offers an intriguing mix of credentials to re-examine the subject.

Who exactly came up with the idea to send a record onboard the Voyager spacecraft and when did that idea materialize?

John Casani, chief of Division 34 at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, was the one who first thought to “Send a Message” onboard the Voyager spacecraft. During the October 1974 Mission and System Design Review for Voyager, in which the entire Voyager JPL team surveyed problems that needed to be solved, Casani used one of NASA’s standard Concern/Action forms to suggest including a message with the two probes.

It turned out that including some kind of human message onboard spacecraft designed for long-term space travel was not new. In December 1971, astronomers gathered in San Juan, Puerto Rico, to attend the 136th annual meeting of the American Astronomical Society. During a break, Carl Sagan, astronomer and soon-to-be-famous space popularizer, met with fellow astronomer and Cornell colleague Frank Drake.

| With the memory of the Moon landings still fresh in people’s minds, it does not seem at all farfetched that this same public would now be willing to accept the idea that onboard a set of spacecraft designed to be sent to the outer planets and beyond, NASA wanted to carry a token message so that, if another lifeform might encounter them, they would know a little about who built these spacecraft. |

Drake was noted for his efforts to put forward a realistic strategy to search for extraterrestrial intelligence. He first did this using radio astronomy. In 1960 his “Project Ozma” sought to listen to a part of the heavens for intelligent life. Shortly after this he formulated what later became known as the “Drake Equation”—a probabilistic argument used to estimate the number of active and communicative extraterrestrial civilizations in the galaxy.

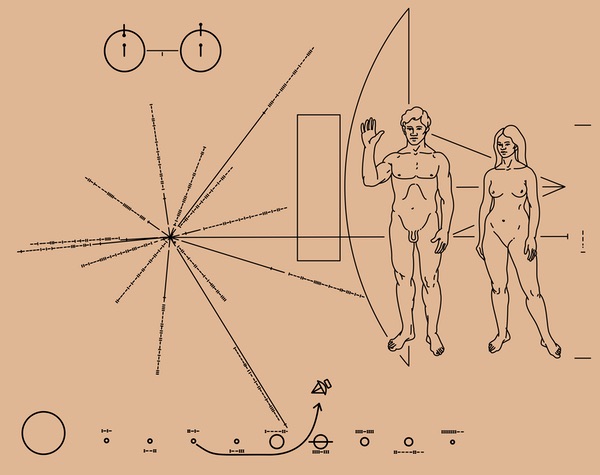

During a coffee break in Puerto Rico, these two put together ideas that eventually led to the creation of the Pioneer plaques. Pioneer 10 and its identical spacecraft, Pioneer 11, were launched in 1972 and 1973, respectively, becoming the first spacecraft to encounter Jupiter. After accomplishing its mission at Jupiter, Pioneer 10 left the solar system while Pioneer 11 journeyed onward to Saturn.

Both spacecraft had mounted to their sides a small gold anodized aluminum plaque. These identical plaques were each etched with several symbols showing the origins of the spacecraft. In addition, the plaque showed two nude figures, one male and one female.

Quite the scandal ensued when word got out that a government agency allowed nude images to not only be printed on a plaque but to then have the plaque be hurled out into space to be seen by who knows what. Cartoonists and commentators had a field day as they lampooned the story at NASA’s expense.

The Pioneer 10 and 11 plaques. (credit: NASA) |

Five years later, and still reeling from the memory of the Pioneer plaques, NASA cautiously approached Sagan to see if he would be interested in working on another plaque, this time for a spacecraft not destined for travel through the cosmos but staying close to home.

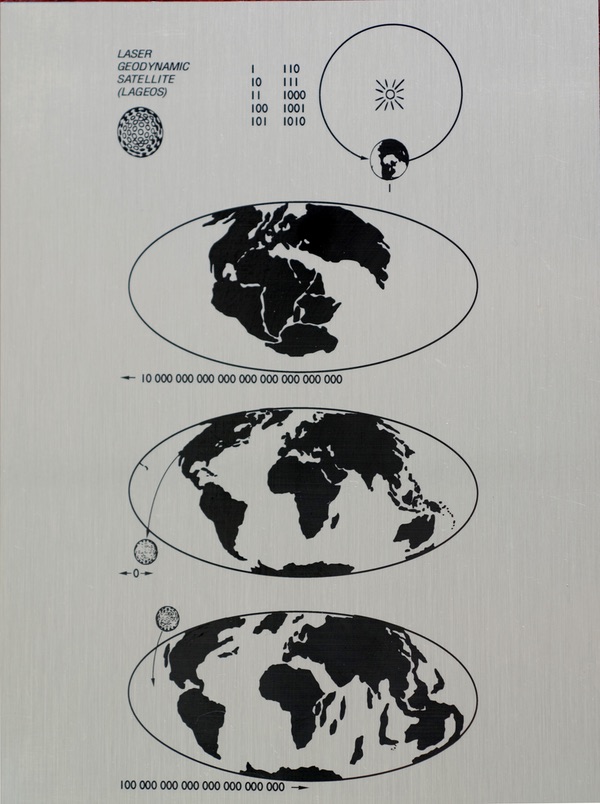

In 1976, NASA was preparing to launch LAGEOS (Laser Geodynamic Satellite), a spacecraft designed to measure continental drift. In order for it to do that, it had to be launched into a highly stable orbit around the Earth, one that scientists determined would keep it in orbit for millions of years (eight million, to be exact.) NASA approached Sagan once again to design a plaque not for aliens but for very distant descendants of the human race. Perhaps because of the spacecraft’s close proximity to Earth and the fact that it might be seen once again by humans millions of years into the future, NASA advised Sagan to nix the nudity, arguing that humans should still look pretty much the same eight million years into the future.

The LAGEOS plaque, like that of the Pioneers, was simple. Etched onto two stainless steel sheets, each measuring 4 by 7 inches (10 by 17.5 centimeters) and mounted at the ends of a bar connecting two hemispheres that make up the golf-ball-shaped satellite, was a simple map that told future earthlings what it was for (to map the changing continents) and to help them figure out when the satellite was first put into orbit.

The LAGEOS plaque. (credit: NASA) |

The US government knew that NASA could demonstrate an ability to inspire. With the memory of the Moon landings still fresh in people’s minds, it does not seem at all farfetched that this same public would now be willing to accept the idea that onboard a set of spacecraft designed to be sent to the outer planets and beyond, NASA wanted to carry a token message so that, if another lifeform might encounter them, they would know a little about who built these spacecraft. As Scott points out, “NASA knew that these messages and time capsules had great potential for generating column inches, interest and inspiration.” As a result of these previously successful space-bound messages, John Casani knew whom to tap to make the message that would be carried into space by the Voyager probes.

Scott tells us that because Sagan had very little time or budget to prepare something for Voyager, he first “pondered simply reproducing the Pioneer plaques as they were” with possible “bonus extras and hidden Easter eggs for any alien collectors out there.”

In December 1976, Sagan “instigated the great brainstorm, calling upon friends, colleagues and academic consultants” for ideas, Scott explains. First on the list was Frank Drake. During this early brainstorming period, art emerged as a dominant theme with one team member proposing they send Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man.”

B.M. Oliver suggested adding sound to the plaque. He first proposed that behind the plaque they could place a magnetic tape that would be played using equipment onboard Voyager. On that tape they could put recordings of voices, other sounds and music. This is the genesis of what eventually would become the Voyager record.

In late January 1977, both Sagan and Drake were attending the 149th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. It was here that Drake first suggested using a metal record.

Scott points out that Drake downplays the idea. “There was no ‘Eureka’ moment,” said Drake when Scott asked him about it. “Today, Frank views the record idea simply as a logical, natural extension to the Pioneer plaque, an obvious next step when faced with the problem of how to squeeze more information onto a metal surface.”

Even though Drake downplays having first come up with the record idea, Scott convincingly credits Drake, and further engages the reader with other notable finds. For example, he reveals the identity of the “laugh” on the record as being none other than Carl Sagan himself.

In another interesting account, Scott explains that one of the few color images encoded on the record is that of a newborn baby. Still glistening with amniotic fluid, the photo was taken in 1946 by Wayne Miller. When the record team called to inquire about securing permission to use the photo, they were shocked to learn that the man who answered the phone was David Miller, Wayne’s son and the baby in the picture.

Scott describes how President Carter submitted a statement for inclusion but chose not to record it using his voice because he thought that “his strong Southern American accent would be an embarrassment to the Earth creatures.” Instead, Carter’s words are preserved in one of the 120 images recorded on the record.

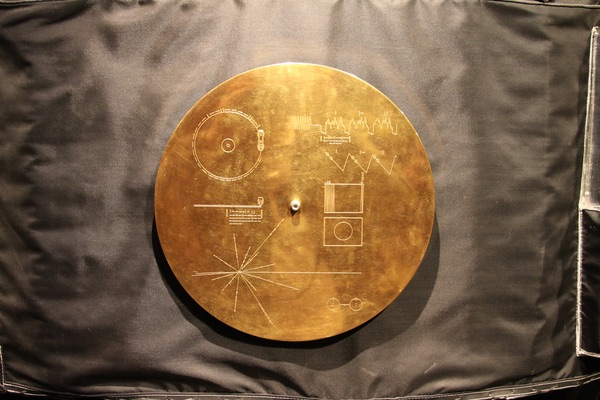

The protective outer cover of the Voyager Interstellar Record as seen on the full-size engineering mockup at JPLs’ Theodore von Karman auditorium. (credit: Glen E. Swanson) |

In many accounts of the record’s creation, it is suggested that the record got more attention than the mission. This makes for good copy but as Scott points out, this is a more recent assessment than historical fact. Jon Lomberg, one of the original record team members mentions in a 2017 interview that what was described about the record’s popularity “wasn’t his experience at all.”

It seems at first that NASA didn’t really know what it had when it permitted Sagan’s team to do the record. Scott notes that even though the Voyager record does not contain naked humans staring at the Cosmos, the six primary members of the Voyager record team—Carl Sagan, Frank Drake, Ann Druyan, Tim Ferris, Jon Lomberg, and Linda Salzman Sagan—produced more potentially embarrassing material that could attract criticism.

The sound of a kiss on the record was recorded when Tim Ferris smooched Ann Druyan, his fiancée, on the cheek. At the time the recording was made, Scott reveals that Ann was in love with Carl Sagan. Shortly after the two Voyager spacecraft launched, Carl would divorce his wife Linda to marry Ann.

| What became known in the press as the “Waldheim Affair” revealed that the very first human voice on the Voyager record was that of a former card-carrying Nazi. |

Scott’s book teaches us more about the record than what was actually known at the time of launch or even for a long time after. Even today while doing a quick check on the Internet of various “official” histories on the record, you will find a visual listing of all 120 images contained in the Voyager record. Each image is numbered with a brief description. Next to image #112, is depicted a color photograph of a Gemini astronaut doing a spacewalk. The official NASA description for the image still lists Jim McDivitt performing the spacewalk when in fact it is astronaut Ed White—the first American to walk in space during Gemini 4.

Some may recall the voice message that Secretary General of the United Nations, Kurt Waldheim made on the record. In the 1980s, during the time that Voyager 2 was approaching Uranus, Waldheim ran for president of Austria and won. During his first term in office, it was revealed that he worked as an intelligence agent for the Wehrmacht, the unified armed forces of Germany during World War II. What became known in the press as the “Waldheim Affair” revealed that the very first human voice on the Voyager record was that of a former card-carrying Nazi.

In addition to the principal team members of the project, Scott includes stories of the myriad of others that worked in the background to make it happen, such as Vladimir Meller, the man who cut the final record. Meller fled from his native Czechoslovakia during the 1968 Russian invasion and eventually reached the United States legally as a refugee, whereupon he began work in New York as an audio-master engineer working for CBS Records. During this time, he took the two-track master recording that the team produced and, using a cutting lathe, cut the master discs into vinyl.

Scott explains that all the engineers and cutters “signed off vinyl records by etching matrix numbers issued by the record company into the run-out groove – that bit on the surface between the end of the grooves and the circular paper label in the center.” Some made a habit of leaving special messages in the run-outs—an analog Easter egg, if you will, but foreign to digital listeners of today. Meller hand-etched on the Voyager record an inscription that reads: “To the Makers of Music - All Worlds, All Times.”

Days before the launch of Voyager 2 (because of the alignment of the outer planets, Voyager 2 was launched before Voyager 1), NASA issued a press release about the Voyager record on August 1, 1977. This caught the media’s attention and, as Scott notes, the press kept pushing and asking about it. As a result, NASA hastily arranged a press conference at Frank Wolfe’s Beachside Motel in Cocoa Beach, Florida. This was the only time during the six-month creation of the Voyager record when all committee members assembled together in the same room. The press conference was held next-door to a Polish wedding that happened to be in full swing. Nothing but a flimsy room divider separated the press event from polka music. Ironically, for a project steeped in the science of sound, Scott explains that the wedding noise was so bad that NASA’s audio engineers gave up trying to record the press conference.

Scott notes that history has been kind to the record with many critics agreeing that, given the incredibly brief time (six weeks) and relative paltry budget (less than $25,000), it is amazing that it turned out at all. Indeed, Scott reminds us all how bad the record could have been.

“The whole thing could have been absolutely strangled by committee, or could have been sponsored and commercialized, turned into little more than a record-label advertisement or back-catalogued sample,” said Scott. Instead “we ended up with a multifaceted cultural artifact complete with flaws. It goes to NASA’s credit that the record remained in the form that it did with relatively little to no publicity during its development.”

Others, Scott admits, argue that the record is a time capsule of inclusivity or an ego trip that would last “billions and billions of years.” Two members of the original record team published books in 1977. Ann Druyan’s A Famous Broken Heart, a fantasy novel and Timothy Ferris’ The Red Limit about the discovery that the universe is expanding both came out the same year that the Voyager spacecraft were launched. Even though these works were not specifically tied to the Voyager record, the added attention that the writer’s received as a result of their involvement in the record’s creation helped in the publicity and sales of their own works.

Finally, as mentioned earlier, Random House published Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record in early 1978. The book, in part, was produced in response to the immense public interest generated by the record. The six principal team members who, as described in the book’s introduction, give the first detailed accounting of “why we did it, how we selected the repertoire and precisely what the record contains.” The book contains everything that was on the record except, of course, the actual audio recordings. It should be noted that Scott quotes heavily from this throughout his book.

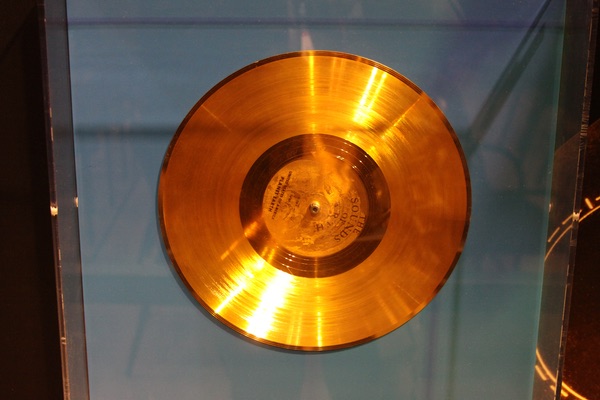

Side 1 of the Voyager record as seen at JPL’s Theodore von Karman auditorium. (credit: Glen E. Swanson) |

In reflecting back on all of this, Jon Lomberg, the team member responsible for helping with the imagery side of the record, states, “I mean, it’s almost operatic. That as far as we tried to sanitize the message, some of the most primal human struggle and basest and rawest emotions got in there anyway… You’ve gotta laugh. It’s cosmic irony.” [This paragraph was corrected to correctly attribute the quote.]

The first CD-ROM version of the record came out in 1992. It was made under the guidance of Jon Lomberg and Frank Drake, both team members that assembled the original Voyager record. Warner New Media issued the CD both as a standalone two-disc set and as a special boxed edition that included a reissue of the book Murmurs of Earth. The CD is pretty rare and remains a collectible.

| Maybe some future alien race will intercept a Voyager record and head to Earth, hopefully not to destroy us, but in search of more Chuck Berry. |

Scott mentions the 2017 Kickstarter campaign launched by Tim and David Daley to produce an LP replica of the record, which they refer to as the “Golden Record,” in time for the 40th anniversary of its initial launch. They only needed $198,000 but raised nearly $1.4 million, revealing there is still strong public interest in the record.

“They produced an incredible product that included a corrected tracklist,” said Scott. The team, named “Ozma Records” in honor of Frank Drake’s famous radio experiment, were “painstaking and obsessive and treated the record with an infectious reverence.” Their 2017 reissue used the original CBS studio masters whereas the 1992 CD-ROM release was only based upon a domestic reel-to-reel tape copy.

One of the more fascinating anecdotes told by Scott is how the Ozma team was approached by someone who was experienced in video encoding. Recall that in addition to containing audio, the Voyager record was also encoded with images. This was done by taking a still photograph, filming it using a video camera and then converting the video signals into sound, which could then be engraved into the record.

Scott explains how this guy asked the Ozma team to send him the original audio readouts of the Voyager photographs so he could try decoding them using only the printed instructions engraved on the outside of the original Voyager record case. He played the record showing how the images appear as they would if the Voyager record were originally played as designed. You can see his results on YouTube.

The book has a few flaws worth mentioning. Nearly half of the Voyager record is devoted to images and Scott goes into great detail describing the back-stories on many of these. However, it is a surprise that his book is devoid of any photos except for the one appearing on the cover.

For example, Scott describes looking at snapshots of team members pouring through images during the final stages of the project, cutting and pasting to review and edit. Scott describes the scene: “There’s one desk covered in coffee-table books with bookmarks and notes. There’s the projector. There’s a video camera, filming another also-ran version of the licking, biting, drinking photograph, and there’s that same photograph being televised on a small black-and-white screen.”

Scott describes still another photo as being “a series of eight acetate overlays depicting human anatomy (that) had to be hand-painted to remove reference numbers, but the paint flecked off.” The image, from World Book Encyclopedia, was originally paired with an index, so that the names of the body parts could be determined by looking up the numbers on them. Scott explains that the Voyager record team ran out of time to fix the flecked off paint so that the image ended up being sent into space covered with numbers that didn’t actually reference anything.

It would be great to have a sampling of these photos present in the book to accompany the author’s detailed telling of their stories. Perhaps there was a rights or licensing issue that the publisher was unwilling to cover in budget, but Scott should have acknowledged this rather than ignoring it.

Scott also makes use of previously unpublished material obtained directly from some of the Voyager record team members. This is great material and adds much to the narrative but I found myself sometimes trying to figure out who said what as it is not always clear when the author chooses to quote this material versus his own words.

Finally, because the author’s background is in music, readers will find that he occasionally drifts away, talking about an offbeat underground music group or London band to make a point. I found this distracting. But these faults are minor and in no way detract from a solid historic narrative told well.

One piece of hardware critical to allowing any alien intelligence to “play” the Voyager record is the stylus. Like any standard vinyl LP, one needs a stylus or needle in order play the record. Voyager engineers included a drawing of the stylus along with a crude illustration of how it is to be used. They even included an actual stylus with each record, safely tucked away in a packet lodged inside the back of the record case. Oddly enough, no known detailed photos of the actual stylus exist. I was hoping that the Ozma Records special remastering or Jonathan Scott’s book might have come across photos. I even contacted the JPL historian and staff members at their history office but they were unable to find any. For now, images of the Voyager record stylus remains a mystery.

In one last ironic twist of fate, Scott tells the story of Wyndham Hannaway, the man in charge of converting the many photographs into sound so they could be recorded on the Voyager record. Scott reveals that Hannaway later worked for Robert Abel and Associates, the folks that did the motion control photography for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, in which Captain James T. Kirk and the crew of the USS Enterprise had to face “V’ger,” which turns out to be Voyager 6. In the 1979 movie, V’Ger was traveling back to Earth after determining that it was the birthplace of the spacecraft’s creator.

Maybe some future alien race will intercept a Voyager record and head to Earth, hopefully not to destroy us, but in search of more Chuck Berry.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.