Stars and Starlinkby Jeff Foust

|

| “This is, unfortunately, just the perfect machine for running into low Earth orbit communications satellites,” Tyson said of the Rubin Observatory. |

OneWeb had just started large-scale deployment of its constellation, with Soyuz launches in early February and again March 21 each placing 34 satellites into orbit. Future launches are now on hold—launch services provider Arianespace was the largest single unsecured creditor identified in OneWeb’s bankruptcy, at $238 million—and may never resume, depending on who buys the company’s assets in a planned sale and their intentions for them.

OneWeb’s constellation of initially about 650 satellites (with plans for future expansion) raised some degree of concern among astronomers. The satellites, in orbits 1,200 kilometers high, were too dim to be seen with the naked eye, but could still interfere with some astronomical observations. Those higher orbits meant that the satellites were also visible longer each night after sunset and before sunrise.

Astronomers had started discussions with OneWeb about studying and potentially mitigating the effect those satellites would have on astronomical research. “We’ve had one telecon with OneWeb, and we hope to follow up with a second one shortly,” said Pat Seitzer, professor emeritus of astronomy at the University of Michigan and member of an American Astronomical Society (AAS) working group studying the effects of megaconstellations on astronomy, at a March 11 panel discussion on Capitol Hill on the issue. “They represent a different challenge.”

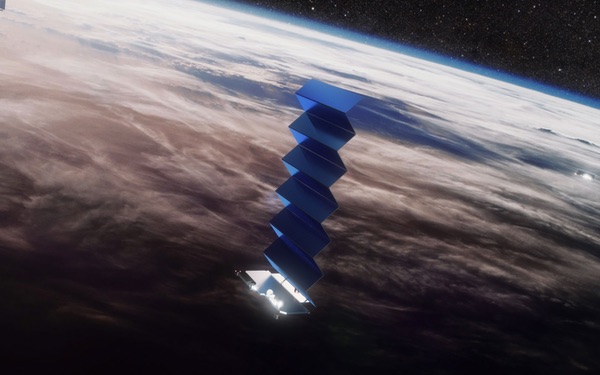

The primary concern of the AAS working group, and many other astronomers, has been not OneWeb but instead SpaceX’s Starlink constellation. Since SpaceX launched the first batch of 60 Starlink satellites last May, many astronomers have been alarmed by the brightness of the satellites, which after launch are visible to the naked eye. The idea of a large constellation of such satellites—1,200 by the end of the year, growing to up to 12,000 and with proposals for 30,000 more satellites—led some astronomers to postulate doomsday scenarios for the field. With a constellation of many thousands of satellites, hundreds could be in view at any given time, producing streaks in images that would ruin those observations.

Just how bad Starlink and other constellations would be to astronomy depends on the observatory. In early March, the European Southern Observatory (ESO) published one study that examined the effects on its Very Large Telescope—four eight-meter telescopes in Chile—and the Extremely Large Telescope under construction that will have a primary mirror 39 meters in diameter. The ESO study concluded both telescopes would be “moderately affected,” particularly around twilight, with up to 3% of long-duration exposures ruined by passing satellites. The effects would be less severe, it noted, for shorter exposures and those taken later at night, when fewer satellites are visible.

The situation is more severe for another telescope under construction in Chile, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, formerly known as the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope and renamed in January after the late astronomer. That telescope, designed for wide-field observations scanning the night sky, could have between 30% and 50% of its observations “severely affected” by satellite constellations, according to the same ESO study.

“This is, unfortunately, just the perfect machine for running into low Earth orbit communications satellites,” said Tony Tyson, a professor at the University of California Davis and chief scientist for the Rubin Observatory, of that telescope at the Capitol Hill panel. (Both Tyson and Seitzer appeared via videoconference in light of the coronavirus pandemic.)

The telescope, equipped with a 3,200-megapixel camera, is designed to create what Tyson described as a “digital color motion picture of the universe” by scanning the sky by taking thousands of 30-second wide-field images each night. That means, he said, “it is most impacted by satellites.”

| “We certainly knew this was a novel spacecraft design in a novel architecture, but the level of brightness and visibility was a surprise to us,” said SpaceX’s Cooper. |

Tyson said astronomers simulated the effect of a Starlink satellite passing through the field of view of a Rubin Observatory observation based on other telescope observations of the satellite. The problem, he said, was not just the streak that bright satellite created, but bands of light elsewhere in the image: electronic artifacts on the detector caused when pixels are saturated by the passing satellite.

“There’s going to be a difficulty,” he said. “We have a serious issue with regard to electronic image artifacts.”

“So,” Tyson later asked, “how do we get out of this mess?”

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory, under construction in Chile, could be severely affected by Starlink satellites that are currently bright enough to cause image artifacts as they pass through the telescope’s field of view. (credit: VRO/NSF/AURA) |

Shedding light on DarkSat

One way is to reduce the brightness of the satellites. SpaceX executives said they were surprised by how bright the satellites were and vowed to take steps to address astronomers’ concerns.

“We certainly knew this was a novel spacecraft design in a novel architecture, but the level of brightness and visibility was a surprise to us,” said Patricia Cooper, vice president of satellite government affairs at SpaceX, during a session on the effects of megaconstellations on astronomy at the 235th Meeting of the AAS in January in Honolulu.

That session took place just a couple days after SpaceX launched its third set of 60 Starlink satellites. One of those 60, dubbed “DarkSat,” featured what Cooper called “various darkening treatments” to reduce its reflectivity. “The goal,” she said, “is to work with the astronomy community to observe and measure the effectiveness of these coatings.”

That couldn’t be done immediately after launch since DarkSat and the other Starlink satellites were deployed into a lower parking orbit and had to maneuver to their planned orbit of 550 kilometers, a process that takes weeks using their electric thrusters. By late February, DarkSat had reached its operational orbit, allowing for true comparisons with the other Starlink satellites.

SpaceX claimed earlier this month that the effort was at least partially successful. “Preliminary results show a notable reduction,” said Jessica Anderson, one of the hosts of SpaceX’s webcast of its latest Starlink launch March 18, said.

That “notable reduction,” though, may not be sufficient for astronomers. In a paper posted online March 17, astronomers said they estimated that DarkSat’s brightness had been reduced by about 55% compared to other Starlink satellites. That conclusion, they noted, was preliminary, and based primarily on a single night’s observations.

If that measurement holds up, though, it falls short of what Tyson said is needed to address the biggest concerns involving the Rubin Observatory. “If we could make those particular spacecraft, the Starlinks, darker by 10 to 20 times, it may remove many of these artifacts,” he said. “It won’t remove the main trail—it will always be there—but it would remove the artifacts so that we might be able to get the science out of the data.”

Tyson and others at the Capitol Hill panel emphasized they were working well with SpaceX, including holding regular telecons to discuss ways to make future Starlink satellites darker. “This is a continuing experiment,” Tyson said of DarkSat. “We’ve had a really delightful collaboration going on now for a couple months with SpaceX engineers. There are a lot of ideas on the table for darkening the satellites. This is just the first.”

| “Guess how many LEO constellations didn’t go bankrupt? Zero,” Musk said. “It would be nice to have more than zero in the ‘not bankrupt’ category.” |

One of those other ideas is a “sunshade” of some kind that would be deployed from the satellite to block sunlight that might otherwise hit highly reflective surfaces of the satellite. In the launch webcast, SpaceX’s Anderson said the company was looking at testing the sunshade on a future Starlink satellite.

SpaceX founder and CEO Elon Musk also mentioned the sunshade when he appeared at the Satellite 2020 conference in Washington March 9. “We are working with senior members of the science community and senior astronomers to minimize the potential for reflection from the satellites,” he said when asked about efforts to reduce the satellites’ brightness. “We’re running a bunch of experiments.”

Musk also said that the constellation will have no effect on astronomy, a claim most astronomers treat skeptically. “I am confident that we not cause any impact whatsoever in astronomical discoveries,” he said. “Zero. That’s my prediction. We will take corrective action if it’s above zero.”

By contrast, Tyson said he was simply hopeful to mitigate the worst effects of the constellation. “The trail will always be there, of course,” he said of the streaks the passing satellites leave on images, “but maybe we can salvage some of the science.”

But for SpaceX, a bigger concern is the financial viability of Starlink in general. At the event, Musk dismissed reports that SpaceX was considering spinning off Starlink and having an initial public offering of stock. “We’re thinking about that zero” right now, he said.

Even before OneWeb’s Chapter 11 filing, Musk said he was aware of the history of past constellation ventures, including those in the 1990s that either went through their own Chapter 11 restructurings or otherwise went out of business. “We need to make the thing work,” he said of Starlink.

“Guess how many LEO constellations didn’t go bankrupt? Zero,” he said. “It would be nice to have more than zero in the ‘not bankrupt’ category.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.