Can NASA land humans on the Moon by 2024?by Jeff Foust

|

| “We are now on our way,” said Loverro. “There are no more puzzle pieces to add.” |

Much of what NASA needed to accomplish the revised goal was already in development, notably the Orion spacecraft and Space Launch System. Both had suffered significant delays but (presumably) would be ready in time to launch NASA astronauts to orbit the Moon, perhaps using the lunar Gateway also under development. What was missing, though, was that last, but most essential, element: a lander to take astronauts down to the surface and then return them to lunar orbit.

No longer. On April 30, NASA announced it had awarded contracts to three companies for its Human Landing System (HLS) program. The awards to Blue Origin, Dynetics, and SpaceX, with a cumulative value of $967 million, will fund initial studies for human lunar lander concepts over the next ten months. NASA will then select one or more companies for full-scale lander development, with the goal of having a lander ready for the Artemis 3 mission before the end of 2024.

“We are now on our way,” said Doug Loverro, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, during a media teleconference to discuss the HLS awards. “There are no more puzzle pieces to add.”

If HLS is the final puzzle piece, exactly what it will look like remains to be seen. The three companies offered very different lander designs, leveraging their distinct capabilities. Blue Origin’s “national team” offered a lander that uses a descent stage based on Blue Origin’s Blue Moon lander, with an ascent stage built by Lockheed Martin. Northrop Grumman will provide a transfer stage that takes the lander from a near-rectilinear halo orbit to low lunar orbit, with Draper providing avionics for the lander.

“This is the kind of thing that’s so ambitious that needs to be done with partners. It’s the only way you can get back to the Moon fast, in my view,” said Bob Smith, CEO of Blue Origin, during the NASA briefing. That team, he noted, has been working together on the lander design for more than a year.

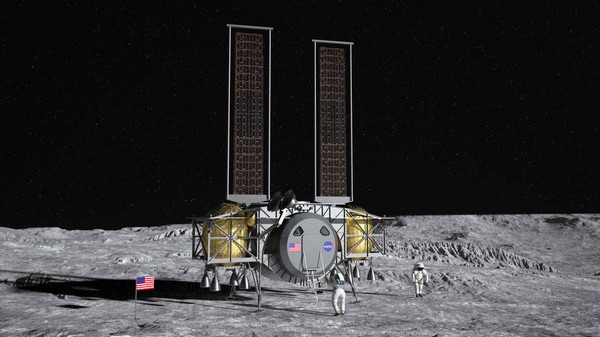

Dynetics put together a much larger team for its lander concept. The Alabama company—acquired by Leidos last December—has 25 partners for its lander concept, including Maxar, Sierra Nevada Corporation, and Thales Alenia Space. (Even Draper, part of the Blue Origin team, is a partner on the Dynetics bid.) It proposed a single-stage lander with a crew cabin close to the ground, ringed by “drop tanks” with engines.

“We are all looking forward to helping NASA achieve the 2024 goal of returning US astronauts to the lunar surface,” said Kim Doering, vice president of space systems at Dynetics, at the NASA announcement.

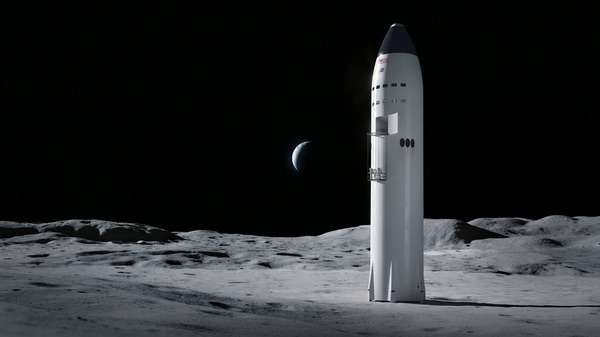

SpaceX, not surprisingly, offered its Starship reusable launch vehicle for HLS, with several different variants. Some Starships will serve as tankers, transferring propellant to a Starship that serves as a depot in Earth orbit. A lander version of Starship will then launch, top off its tanks at the depot, and head to the Moon.

That architecture would offer far larger payload capabilities than other landers, something that SpaceX CEO Elon Musk hinted at in the NASA announcement. “We look forward providing the capability that we’ve bid as well as, potentially, a lot more over time,” he said.

The lunar lander concept by Dynetics, leading a team of 25 companies and organizations. (credit: Dynetics) |

NASA officials like Loverro said the number of companies, and diversity of designs, made them optimistic about the prospect of making the 2024 deadline. “I’m very bullish on the fact that I believe that it’s absolutely possible for us to do so,” Loverro said at a May 13 meeting of the NASA Advisory Council’s Human Exploration and Operations Committee.

| “We look forward providing the capability that we’ve bid as well as, potentially, a lot more over time,” Musk said. |

Many are skeptical, and point to the experience developing the lunar module, or LEM, for Apollo as a reason why a lander won’t be ready by the end of 2024. NASA awarded the LEM contract to Grumman in November 1962, but the lander didn’t carry Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to the lunar surface until July 1969, more than six and a half years later. NASA only has a little more than four and a half years to make it to the Moon this time.

Loverro, at the committee meeting, argued two factors will allow NASA to go faster this time. He showed a slide with a schedule of the LEM development, highlighting a gap of more than two years between the lander’s preliminary design review (PDR) in September 1963 and its critical design review (CDR) in January 1966.

“The cause of that slip, as we traced it back, was because the requirements changed drastically between PDR and CDR,” he said. “When the requirements change, you have to go back and redo all the work that led to the preliminary design review before you can go to the critical design review.”

With HLS, NASA plans to set the requirements early and not change them. “We have got to make sure we have the requirements for this system right,” Loverro said at the media telecon. “An extra month that we take in the very beginning to make sure that we have the requirements right will save us a year on the back end.”

Lisa Watson-Morgan, NASA’s HLS program manager, said that the first three months will be spent with the companies to settle on the various standards, developed either by NASA or the companies, that will be used for each company’s lander. “There are many programs that spend years arguing back and forth about standards,” she told the committee May 13. “Our first three months are critically important to us.”

A second factor that gives Loverro confidence about meeting the 2024 deadline is technological maturity. “We were inventing technology for the first time during the LEM development,” he told the committee. “We are not so constrained now, under the current Artemis program.”

Yet the source selection statement for the HLS program—the NASA document that outlines the strengths and weaknesses of the three selected proposals—raised questions about technological readiness. “Many of the technologies upon which these capabilities rely have yet to be developed, tested, or demonstrated; the challenge that lies ahead is formidable,” it stated.

NASA reviewers warned that Blue Origin’s design requires “what appears to be an aggressive timeline” to be ready by 2024. Dynetics’ lander needs “technologies that are at relatively low maturity levels or that have yet to be developed” but would have to be matured “at an unprecedented pace.” SpaceX’s overall concept of operation creates risks that “threaten the schedule viability of a successful 2024 demonstration mission.” (SpaceX was also dinged by NASA reviewers for “considerable schedule delays” on both the commercial crew program and development of the Falcon Heavy launch vehicle.)

The lunar lander concept by SpaceX, derived from its Starship reusable vehicle. (credit: SpaceX) |

Near the end of the two-day NASA Advisory Council committee meeting May 14, members discussed potential findings and recommendations to send to the full council. That discussion revealed skepticism among many members that a landing by 2024 was feasible.

“I think the whole HLS schedule, the thought that they can develop this system and land on the moon in four years with these systems that they have in front of them, is a pipe dream,” said Tommy Holloway, a former NASA shuttle and space station program manager. “There’s no way that they’re going to get there.”

He was not alone. “I think there’s a pretty good consensus among the committee members that the likelihood of making the landing by 2024 is really, really remote,” said Pat Condon, an aerospace consultant. That issue “has been kind of the elephant in the room for the last two or three meetings,” he said, and the latest presentation by NASA did little to ease his skepticism.

| “I think the whole HLS schedule, the thought that they can develop this system and land on the moon in four years with these systems that they have in front of them, is a pipe dream,” said Holloway. |

Another issue about HLS was NASA’s use of public-private partnerships to develop the landers, with fixed-price contracts and eventual plans to purchase lander services, rather than the landers themselves. Condon noted that the commercial crew program, which used a similar model, is just now getting ready to launch astronauts after a delay of more than three years. “I would assert that we know an awful lot more about putting a crew in low Earth orbit than we know about landing a crew on the Moon, yet we’re going to execute that [lunar lander] development in half the time,” he said.

Loverro, asked about the use of the commercial model during the committee meeting, said it would be, at least initially, closer to a more conventional relationship between the agency and each company as they develop their landers. “The word ‘commercial’ is the wrong way to describe it,” he said. “The right way to describe it is that we’ve entered into a collaborative relationship with contractors not that different than we used to.”

Others are more optimistic. “The approach that NASA is using with industry, with a broad agency announcement, firm fixed price contracts, and a lot of things happening in parallel, has allowed NASA to move extremely fast,” said George Nield, a member of NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP), during a May 15 meeting. “It will clearly be challenging to make the 2024 goal, but so far, it looks like NASA is doing everything it can in terms of strategic planning, programmatic decisions, and contract actions to keep things on track.”

NASA does face a couple major challenges, he acknowledged. One is the budget the agency will get in 2021 and future years to keep the HLS program, and the rest of Artemis, on schedule, and the other “defining and executing to a realistic schedule.” That latter challenge, he said, could be affected by the coronavirus pandemic that has slowed many NASA programs.

The pandemic could also affect the first challenge, funding. Congress has yet to start work on spending bills for fiscal year 2021, which starts October 1. While NASA usually starts a fiscal year on a CR, or continuing resolution—a stopgap spending bill that funds programs at the previous year’s levels—for up to several months, the pandemic increases the odds that Congress may settle on a full-year CR. That would be a problem for the HLS program, since NASA requested a significant budget increase for it in 2021 that would not be possible in a CR.

“The ASAP has spoken of the risks of continuing resolutions multiple times, and our concerns definitely apply to the HLS development,” said Patricia Sanders, chair of the panel. “A CR would add risk to an already aggressive development.”

NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine has said on several occasions, including at the HLS announcement and later events, that he is not worried about NASA’s budget, citing bipartisan support for the agency in Congress. He suggested NASA could be included in a future bill to fund infrastructure projects as part of a post-pandemic economic stimulus effort, although House and Senate leaders have set no schedule for considering such a bill this year.

The NASA Advisory Council committee meeting was the last for Holloway, who was one of three members rotating off the committee. Asked near the end of the meeting for any final thoughts or words of advice for the committee, he said, “You guys have a tall order if this ’24 thing stays on track. My only advice would be: tell it like it is.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.