Space resources: the broader aspectby Kamil Muzyka

|

| The fact of the matter is that obtaining mineral resources, volatiles, organics, hydrocarbons, and isotopes in outer space is not only a matter of profit, but of survival and sustainability. |

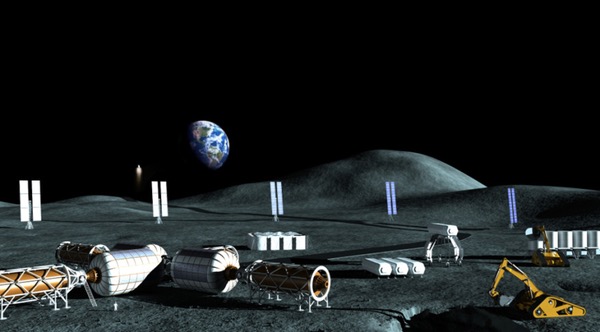

But space resources are something more than simply chunks of metals floating in outer space. The ability to obtain, process, and utilize a given material or energy source means profit, but not in the direct way that it might be seen. In Situ Resource Utilization boils down mostly to the following phrase: if you possess the proper means, everything can be a useful resource. Water, and oxygen and hydrogen derived from it, has been discussed as propellant for space tugs and other vehicles for decades. But water rockets don’t make the same headlines as trillions of dollars’ worth of raw ore. Regolith, if properly fined, uniformed, and processed, will be a useful long-term resource for lunar settlements and robots.

The fact of the matter is that obtaining mineral resources, volatiles, organics, hydrocarbons, and isotopes in outer space is not only a matter of profit, but of survival and sustainability. Astronauts and others will require nutrition, housing, life support, tools, and equipment. And even if they aren’t people but instead teleoperated or autonomous robots, they would require the means to prolong their “lifespan” by being provided with repairs, spares, consumables, and other maintenance. This requires a whole industrial ecosystem that would be mostly dependent on in situ resources. Robots extracting, transporting, building, and repairing. Other machines processing, manufacturing, and generating power. Perpetuation of such ventures, with space tugs, orbital yards, and factories, requires energies and materials and sufficiency. This whole network of object needs to be as “self-repairing” as possible.

The use of extraterrestrial resources might provide us with different modes of production and an approach to self-sufficiency in outer space. Americans used to refer to outer space as the Final Frontier, using analogies to homesteading. However, the current state of international space law and other acts relating to space forbids claims of sovereignty by occupation and means of “working the land.” Nonetheless, people operating robots or living on the moon for some time will develop their new ideas of obtaining and using resources, with their own sort of life-hacks, knowhow, and inventions.

There have been a lot of publications describing the use of said resources and what processes can be performed on orbit. NASA’s NTR Server is full of such studies, speculations, and plans. Chinese Earth-Moon economic zone papers on solar powered satellites, published by Chinese academicians, look very similar to those published before and during the early operation of the shuttle. Don’t call it plagiarism or re-writing one’s homework: if some designs look plausible and feasible, they will be pursued. If lunar telescopes, orbital tugs, and nuclear shuttles look like an idea worth pursuing, and the previous pursuer ran out of steam, why wouldn’t you pick up the idea, work on it, and even improve it?

Therefore, any new regulation for commercial utilization of celestial bodies (or, rather, certain categories of such) should include the following:

- Safety and security of operations

- Governance and reciprocal approach to authorization of space activities

- Dispute resolution

- A platform for information sharing for commercial, safety, and scientific use

- A framework for processing, manufacturing, and construction using space objects with the use of obtained resources

- Liability for damage caused by people and machines

- The use of synthetic organisms within space objects or on the surface of a celestial body

- Addressing the issues of extraterritorial intellectual property suits.

- Recommendations for space debris removal, recycling, reuse, and protection of national heritage sites (space objects and their direct vicinity) on the surface, subsurface, atmosphere, or orbit of a celestial body.

The problem of benefit sharing gets a little murky here. Earth orbits are frequently recognized as “global commons,” but the Moon is a globe of its own. And extending the idea of global commons beyond the Earth-Moon system would be anti-Copernican, to say the least! Yet providing “non-mining” nations with capacity-building programs or cosponsored lease of industrial space objects (such as it is the case with some telecom satellites) would be a greater benefit to be shared than creating a “you-fly-and-I-don’t” tax and other forms of monetary benefit sharing. This notion of monetary benefit sharing stems from the simplistic understanding of space resources as “gold mines.” These are not gold mines: here one person’s overburden is another person’s shielding material. Of course, there is different value and use for different materials, yet creating taxes for space resource utilizers will cause more trouble than it will solve problems.

| Obtaining resources is merely a tool, not the goal. Yet in order to understand the goal, one must overcome one’s mental gravity well. |

Even if some spacefaring nations or their nationals find a way to dodge this tax or other form of compulsory monetary benefit sharing, the idea itself is very populist and will be a dangerous tool of international politics. It can be said, that the money made by “space miners” can be redistributed to help mitigate climate catastrophes and provide a better life for people in the developing world. If the saying about “not being able to eat money” has any truth to it, then we either need to think about solutions involving the use of space resources and outer space more generally (outside of the current use of climate monitoring), or else brace ourselves for new chapters in the history of corruption, ruined dreams, local activists silenced. and getting rich off helping the poor.

Space resource utilization, be it out there or down here, should be mainly regulated by an intergovernmental agreement (IGA), such as the IGA for the International Space Station, if the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space is no longer a proper platform to discuss the matter. State parties to the IGA would establish their own stations, platforms, vehicles, and other means of operation and create a reciprocal set of rules, rights and obligations. Some principles or ready templates have been proposed by the Outer Space Institute, The Moon Village Association, and The Hague Working Group, whose Building Blocks give a promise of balance as they neatly fit the parties to the Outer Space Treaty and address the concerns of states that are party to the Moon Agreement. The sooner the rules will be settled and agreed upon, the sooner we can move on to next regulations for the “poly-global” space economy. Obtaining resources is merely a tool, not the goal. Yet in order to understand the goal, one must overcome one’s mental gravity well.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.