The Artemis Accords: repeating the mistakes of the Age of Explorationby Dennis O’Brien

|

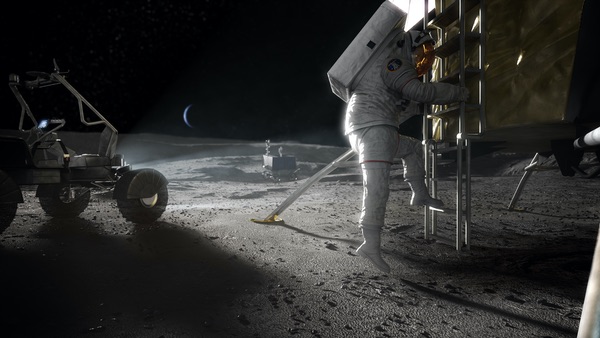

| The Outer Space Treaty was an intentional effort to avoid the mistakes of the Age of Exploration & Empire. |

This is the first lesson that the current governments of the world can learn from the Age of Exploration & Empire that began five centuries ago. Even then, the most powerful nation in Europe, with the largest army and most advanced technology, realized that it could not unilaterally establish property rights or any other kind of sovereignty without the approval of an international authority. After the Church granted that authority, Spain was able to create one of the greatest empires in history. Spain and Portugal formalized the arrangement with a binding international agreement, the Treaty of Tordesillas, whose purpose was to ensure peaceful cooperation between their nations, primarily by establishing a line of demarcation that separated their areas of activity.[3]

Unfortunately, the legal framework so established was based on national dominance, not multilateral international cooperation. The grant of sovereignty was exclusive, made only to Spain and Portugal, and it required them to subjugate the “savages” in the lands they discovered by taking along Church missionaries. This exclusivity did not sit well with other nations as they also developed the technologies of exploration; it was one of the reasons many northern European nations joined the Protestant Reformation and rejected the authority of the Pope in Rome. Without a fair and equitable international agreement that honored the interests of emerging states, the Church lost its ability to act as an arbiter between nations.

Even worse, the dominance model set up centuries of conflict among the major powers in Europe. Militant nationalism and economic colonialism became the principles guiding national policy. The result was centuries of war, suffering, and neglect among the major powers and the nations they subjugated. This pattern did not end until the 20th century, when the major powers fought two world wars and finally dismantled their colonial empires: sometimes peacefully, sometimes by force.

By the mid-1960s, most countries on Earth were independent or on their way to becoming so. But a new conflict had started, one that threatened to repeat the mistakes of five centuries earlier. The great powers were once again using their advanced technology to explore new worlds, and the race was on to plant their flag on the Moon first. Under the ancient traditions, the country that did so would have a claim against all others for possession and use of the territory. The Cold War was about to expand into outer space.

But then something wonderful happened. In 1967, the United Nations proposed, and the world’s space powers accepted, an international agreement known as the Outer Space Treaty.[4] The treaty was an intentional effort to avoid the mistakes of the Age of Exploration & Empire. Article I states, “The exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development, and shall be the province of all mankind.” Article II is even more specific: “Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” Because of this treaty, the United States carried a plaque to the Moon that said, “We came in peace for all mankind.”[5] When the Apollo 11 astronauts planted the US flag, they did so out of pride, but did not establish any claim or national priority.

This legal framework worked well initially, but people soon started wondering about what to do when countries or private entities wanted to start commercial activity on the Moon, or build settlements. The solution was the Moon Treaty, proposed by the United Nations and adopted by enough nations to come into force in 1984.[6] But it has not yet been adopted by any major spacefaring nation. The United States, by a recent executive order, has specifically renounced the treaty and stated its intentions to extract materials from the Moon without any international agreement.[7]

| Despite the lessons of history, the United States is going full speed ahead with the “dominance” model of space development rather than working with the nations of the world to develop a “cooperation” model. |

The newly announced Artemis Accords go even further. Although the actual Accords have not been released pending consultation with possible partners, the summary provided by NASA[8] indicates that the United States will unilaterally interpret the Outer Space Treaty to allow “space resource extraction,” despite the prohibition against appropriation in Article II of the Treaty. There will also be “safety zones” to avoid “harmful interference” with such operations. The effect is to establish exclusive economic zones, especially if “harmful interference” is defined to include economic harm, not just safety. Will the new Space Force be used to protect such economic interests? Will other nations be excluded if they support the Moon Treaty?[9] Will private actors be required to follow the same rules as states, as recommended in the recently drafted Moon Village Principles?[10] This is the slippery slope of using unilateral action to establish economic rights rather than an international agreement.

The Artemis Accords acknowledge many beneficial agreements and policies: The Outer Space Treaty, Rescue Agreement, and Registration Convention (though not the Liability Convention); peace, transparency, interoperability, protecting heritage sites and sharing scientific information. But its unilateral authorization of space mining is a continuation of the Trump Administration’s underlying foreign policy strategy: unilateral dominance over international cooperation. The United States has withdrawn from the Paris Accords, the Iranian nuclear deal, and, in the middle of a pandemic, the World Health Organization. Dominance has even become the theme of the administration’s domestic policy, with President Trump recently telling governors, “If you don't dominate, you're wasting your time… You have to dominate.”[11] That core philosophy is now being applied to outer space, as Vice President Mike Pence proudly announced in 2018. Despite the lessons of history, the United States is going full speed ahead with the “dominance” model of space development rather than working with the nations of the world to develop a “cooperation” model. Outer space, which so far has been preserved for peace and cooperation, is about to be spoiled, perhaps forever.

But if the Moon Treaty is the key to peaceful cooperation in outer space, why haven’t more nations adopted it? The reason appears to be that the treaty is incomplete, and thus flawed. Article 11 requires an implementation agreement to create the legal framework for private activity. Without that agreement in place, some states fear the worst, that they will lose their sovereignty if they adopt the treaty, especially since it refers to outer space as the “common heritage of mankind.” Private mining interests are afraid that their profits will be taxed for redistribution to less-developed countries. As one space law scholar put it:

Some would say the biggest challenge for the implementation of the Moon Agreement are four little words found in Article 11… the “common heritage of [hu]mankind”… At first glance, it appears that to implement the concept of common heritage of humankind, an international body must be created to redistribute wealth and technology among nations.[12]

Some even wonder if they will be able to market the materials they extract. As recently explained by an attorney for the mining industry:

Here’s the issue on the security of tenure [the right to extract materials] and the fiscal regime: there’s an Outer Space Treaty that was signed by a lot of countries when the moon exploration was going on, and the treaty includes a provision that says you can’t appropriate celestial bodies, that would include the moon.

The question is — what happens if I go to the moon? I set up shop, and I extract ice and rocks and start making things, do I own the rocks that I’ve extracted? I’m not saying that I own the moon, but if I put in the effort, do I own the resources? Same thing with asteroids, if I send a robot to the asteroid, it sets up shop and starts extracting things and using them, do you own the extracted mineral? And that’s the legal issue, that’s the unsettled question. [13]

Until the rule of law is extended to the Moon by such an international agreement, there will be great uncertainty as to the viability of commercial activities. It is an axiom of economics that businesses and investors hate uncertainty, as it makes it impossible to analyze risk and estimate the return on investment.

| Until the rule of law is extended to the Moon by such an international agreement, there will be great uncertainty as to the viability of commercial activities. |

The solution is to create an implementation agreement that addresses these concerns and can be adopted along with the Moon Treaty. To that end, a Model Implementation Agreement has been drafted by The Space Treaty Project. It was first distributed for comment in 2018 and made its public debut at the 2019 Shanghai Advanced Space Technology conference. It has recently undergone peer review and was published in the Journal of Advances in Astronautics Science and Technology.[14]

The Model Implementation Agreement has only ten paragraphs and is based on four organizational principles:

- The Agreement must be comprehensive and support all private activity;

- The Grand Bargain: Trade private property rights for public policy obligations;

- Defer issues currently at impasse (e.g., monetary sharing of benefits) by creating a governance process for making future decisions;

- Integrate and build upon current institutions and processes.

The Model Agreement supports all private activity by defining the “use of resources” to include the use of any location on the Moon for any purpose, much the same way that real estate and property rights are considered resources on Earth. Any use would be supported if the private activity is authorized/supervised by a country that has adopted the Moon Treaty and the implementation agreement, because any country that has done so has agreed to the public policy obligations therein and to require that their nationals abide by them.

What are the obligations of the Moon Treaty that the countries and their nationals must accept? They are summarized in paragraph 4 of the Model Agreement:

4. Public Policy Obligations

The States Parties agree that the public policy obligations of the Treaty and this Agreement include the following:

- Use outer space exclusively for peaceful purposes (Article 3.1);

- Provide co-operation and mutual assistance (4.2);

- Honor the Registration Convention and inform the public of:

- Activities (5.1)

- Scientific discoveries (5.1)

- Any phenomena which could endanger human life or health (5.3)

- Any indication of organic life (5.3)

- The discovery of resources (11.6)

- Any change of status, harmful impacts of activities, use of nuclear power, and links to websites for specific objects/activities [COPUOS recommendations]

- Protect the environment and preserve areas of “special scientific interest” such as historic landing sites (7.1-7.3);

- Allow free access to all areas by other parties (9.2);

- Honor the Rescue Treaty (10.1)

- Share technology as part of sharing the benefits of outer space with less technologically advanced countries (4.1-4.2)

The full Model Agreement is available here.

Most of these obligations are already established in other widely adopted treaties, i.e., the Outer Space Treaty, the Rescue Agreement, the Registration Convention, and the Liability Convention. Even the Artemis Accords acknowledge many of them. But there are some that are not acknowledged, such as sharing the discovery of resources, protecting the natural environment, and sharing technology. The Accords are also silent as to whether its obligations will apply to private parties.

Sharing technology is not specified in the Moon Treaty, but some view it as included in Article 4: “The exploration and use of the moon shall be the province of all mankind and shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries, irrespective of their degree of economic or scientific development.” The “Building Blocks” of The Hague Spaces Resources International Working Group call for sharing technology on a “mutually-accepted basis”.[15] The Working Group members were “stakeholders of space resource activities and represent consortium partners, industry, States, international organizations, academia and NGOs.”[16] It is significant that stakeholders from the private sector are willing to consider the sharing of technology. If a “mutually-accepted basis” for sharing cannot be found, the Model Agreement would require the licensing of technology at fair market value.

Accepting the obligations of the Moon Treaty is the tradeoff for private property rights, the “Grand Bargain” in the organizational principles. They are no more onerous or burdensome than the obligations that property owners must accept on Earth. Here, property owners must always consider what effect activity on their own property will have on others. Property on Earth is subject to regulation (e.g., zoning, permits, safety) and can be taken (with compensation) for public policy reasons. It is unreasonable to expect that the use of property on the Moon will not be subject to similar regulation.

| We can continue to preserve outer space for peaceful cooperation, or we can extend the pattern of domination and conflict that for too long has controlled our destiny on Earth. |

The Model Agreement contains other provisions, such as controlling law, dispute resolution, and future governance for substantive decisions. It also protects the rights of individuals and those wanting to establish private settlements: “Nothing in this Agreement or in the Treaty shall be interpreted as denying or limiting the rights guaranteed to individuals by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, or the right of settlements to seek autonomy and/or recognition as sovereign nations.” (Paragraph 10) By providing legal support for all private activity, protecting individual rights, and maintaining essential public policies, the Model Implementation Agreement satisfies all concerns about the Moon Treaty and creates a practical, cooperative alternative to the unilateral and exclusive dominance model being proposed by the United States.

The current Model Agreement is the product of consultation with many individuals and organizations over the past three years. It now being presented for consideration as a reasonable alternative to the Artemis Accords. If adopted, the Agreement will have a significant advantage over the Accords in that, like all treaties, it will be an enforceable international agreement that is binding on the States Parties, not just a unilateral action by one country with a few activity partners. It will also be comprehensive, supporting all private activity, not just materials extraction like the Accords. And it will include an overall framework for international cooperation, including controlling law and dispute resolution, none of which are included in the Accords.

We have become familiar with the Overview Effect, that fundamental change in attitude that comes from viewing the Earth from space, as with the picture of Earthrise taken from the Moon in 1968. We must now take an overview through time. Humanity is on the verge of leaving the home planet. It is the greatest adventure and opportunity in our history, but it will be an opportunity lost if we repeat the mistakes of the last Age of Exploration. We can continue to preserve outer space for peaceful cooperation, or we can extend the pattern of domination and conflict that for too long has controlled our destiny on Earth.

At this most pivotal moment in history, the choice is ours.

References

- Washington Post, videos of U.S. Vice-President Mike Pence: “Space is a warfighting domain”, October 23, 2018. “We must have American dominance in space”, August 9, 2018.

- Bulls of Donation (1493), Wikipedia (Three papal “Bulls of Donation” - Inter Caetera, Eximiae Devotionis, and Inter Caetera (2) - were issued May 3-4, 1493, and a fourth - Dudum Siquidem - on September 26, defining the terms of the “donation” of lands to each country).

- The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), Wikipedia.

- Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (The Outer Space Treaty, 1967), United Nations Office of Outer Space Activities (UNOOSA).

- Lunar Plaque, Wikipedia.

- Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (The Moon Treaty, 1984), UNOOSA.

- Executive Order on Encouraging International Support for the Recovery and Use of Space Resources, The White House, April 6, 2020.

- NASA, The Artemis Accords (2020).

- “Australia would be obliged to withdraw from the Moon Treaty if it accepts an offer to join the Accords.” Mark Whittington, How the United States plans to make space exploration pay, The Hill, April 26, 2020.

- “States shall authorize and continually supervise all lunar activities of their nationals in order to ensure compliance with international law.” Moon Village Association, Moon Village Principles Issue 2 (draft), March 5, 2020.

- David Choi, 'Exactly what President Trump wants': Democratic governors are shunning Trump's calls to 'dominate' protests using military forces, Business Insider, June 1, 2020.

- Michelle Hanlon, What is the Moon Treaty and is it still useful?, Filling Space, May 14, 2020.

- Stutt, Amanda, How Earth-bound Mining Lawyers Think About Space Mining (interview with Scot Anderson, attorney and Global Head of Energy & Natural Resources with the law firm Hogan Lovells in Denver, Colorado), Mining.Com, Jan. 3, 2020.

- O’Brien, D. Legal Support for the Private Sector: An Implementation Agreement for the Moon Treaty. Adv. Astronaut. Sci. Technol. (2020).

- The Hague International Space Resources Governance Working Group, Building Blocks For The Development Of An International Framework On Space Resource Activities (13. Sharing of benefits arising out of the utilization of space resources), November 2019.

- The Hague International Space Resources Governance Working Group, International Institute of Air and Space Law, Leiden University (2019)

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.