Mars race rhetoricby Ajey Lele

|

| Now, with the launch of these three missions, some claim a Mars race has begun. |

Mars always has been an enigma to the global scientific community. Only four entities so far have entered the Martian orbit successfully: the US, Russia, the European Space Agency (ESA), and India. The launch of a Mars probe is limited to a launch window that becomes available only every 26 months. The latest such window was available during July and August of 2020. All the three missions planned for this window have been successfully launched by the United States, China, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). These missions will take seven months to reach Mars and are expected to arrive at Mars in February 2021. (Europe and Russia originally planned to launch their ExoMars 2020 lander mission, but technical issues and the coronavirus pandemic delayed it to 2022.)

The first Arab space mission to Mars, an unmanned probe named “Hope” (Al-Amal in Arabic) was successfully launched from Japan on-board of H-2A rocket on July 20. On July 23, China successfully launched its Tianwen-1 mission on a Long March 5 rocket. Seven days later, on July 30, the US Mars 2020 mission, with the Perseverance rover, successfully began its journey towards Mars. It was launched by the Atlas V 541 rocket.

In recent years, the only new country to successful launch a Mars mission was India. India’s Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM or Mangalyaan) which is satellite that weighs 1,350 kilograms, has been orbiting Mars since September 2014. This satellite was designed to survive for six months, but it has now lasted almost for almost six years and is still partially operational.

Now, with the launch of these three missions, some claim a Mars race has begun. Since these nations are looking at Mars not jointly but individually, there is a possibility that they want to outdo each other; hence, the possibility of Mars race gains credence. Are the Mars missions recently launched comparable? Are the states launching these missions are trying to outdo each other? There is a need to put into context the notion of a so-called “Mars race” both from geostrategic/geopolitical and technology perspectives.

UAE’s Hope is expected to remain in orbit for one Martian year which corresponds to the 687 earth days. This orbiter is a 1,350-kilogram spacecraft to study the Martian atmosphere using three instruments. The entire mission cost, including the launch, is around $200 million. This detailed knowledge of the atmosphere of the Mars would be of great relevance for planning the futuristic human settlement of Mars.

The Chinese Mars probe named Tianwen-1, with a total mass of 5,000 kilograms, is aimed at achieving three key objectives: orbiting the Red Planet for comprehensive observation, landing on the Martian surface, and sending a rover to travel from the landing site. It would conduct scientific investigations into the planet’s geology, atmosphere, and water. The 240-kilogram rover would explore the planet for 90 days. Before landing, the orbiter would use high-resolution cameras to identify a suitable landing site on the surface.

An onboard ground-penetrating radar equipment would be used by Tianwen-1 after landing to study the planet’s internal structure at depths of between 10 and 100 meters. That is one of 13 instruments on the overall mission: seven on the orbiter and six on the rover. Instruments on the orbiter are to study the geological composition of the Martian surface, while the sensors on rover would focus on mineralogy and magnetism.

| Can the ambition of a few nations to seek evidence of the habitability of a distant planet be treated as an act of competition? |

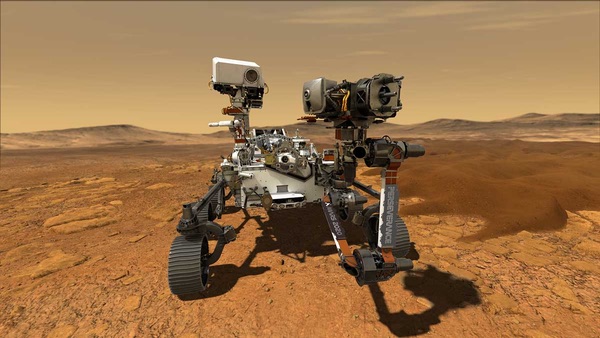

The Perseverance rover of the Mars 2020 is a technological marvel. This US$2.7 billion plutonium-powered system will attempt to collect rock samples for later return to Earth. However, getting those samples back would require the US to undertake additional missions, collaborating with ESA to get the samples back around 2031. This robot has been designed to work for at least one Mars year and would hunt for signs of any possible fossilized life. It has microphones to capture the sounds of Mars. It is carrying a technology demonstration called Ingenuity, a 1.8-kilogram helicopter.

Now the question is, what do these new missions, as well as recent ones like MOM, have in common beyond exploring Mars? Can the ambition of a few nations to seek evidence of the habitability of a distant planet be treated as an act of competition? Such missions are more about human curiosity and desire to challenge one’s self to realize the unachievable technologically. Every country has its own reasons for development of technology, and hence to label these missions as a “race” is a mistake.

More importantly, there is a need to critically evaluate the technological capabilities at display during all these missions. UAE is a relatively recent entrant in to this field. They do not have satellite launch capabilities of their own and were able to launch their mission with the help of a Japanese rocket. The missions of UAE and India are orbiter missions only. They each cost around $100–200 million.

The basic similarity between the US and Chinese missions is that both the involve the landing of robotic systems on the surface of Mars. However, for the US mission the rover itself is 1,025 kilograms, while China’s rover is only 240 kilograms. The US has extensive experience of landing on Mars while, for China, this is going to be their first attempt. So far, the US has sent four rovers to Mars: Sojourner, Spirit, Opportunity, and Curiosity, landing between 1997 and 2012. From a technology perspective there could be some limited comparison between the US and China, but the US is far ahead than China in this domain. Broadly, from technology perspective, the concept of “race” among these countries is a fallacy.

Today, the US is the world's largest economy and China is second. At a geopolitical level, US-China relations are at a nadir. China fully appreciates the role played by technology to assist the US to achieve the so-called superpower status. They could be trying to outdo the US in the field of technology. However, are fully aware that achieving overall technology supremacy is a very difficult proposal and thus probably are choosing only a few fields to demonstrate the power of technology; space could be one such field. China could be trying to match the US, project by project and program by program, in the domain of space, be it human missions or planetary exploration. However, Chinese programs are dwarfed by far larger American ones.

In the domain of space, there is little comparison between India and China. China is far ahead of India in almost every domain of space—except Mars, where India got there first. Yinghuo-1 was China’s Mars probe launched during November 2011, part of the Russian Fobos-Grunt sample return spacecraft. However, that Chinese probe could not reach Mars since the Russian craft failed to depart Earth orbit. It needs to understood that, Yinghuo-1 failed owing the failure of the Russian craft.

| Nations would go to Mars only when they have clarity about their scientific focus and have capacity (both technical and economic) to develop spacecraft for such purposes. It is highly unlikely that, in the 21st century, nations will race against each other to conquer Mars. |

The Tianwen-1 mission launched by China is technologically far superior to India’s MOM. China has developed expertise for soft-landing on the Moon (Chang’e-3 and Chang’e-4) and successfully operating a rover and lander system. With Tianwen-1, they are going to repeat the idea on the Martian surface. Unfortunately, India has not be able to cash in on the success of their first mission to Mars. Their second mission to Mars in not on the horizon, although it may happen in 2024. Obviously, a decade’s gap between two missions suggests a lack of clear scientific focus. Also, India has failed in its first attempt last year to operate a rover-lander system on the surface of the Moon.

Given this backdrop, it becomes evident that any talk of a “Mars race” is a bit premature. There is a view that China seeks to send the humans to Moon by 2030 mainly for the purpose of demonstrating its technological superiority to the rest of the world. But, are Mars missions viewed as instruments for demonstrating power?

Here the answer could be both yes and no. Yes, because it does help to raise the prestige of a nation. However, the quantification of such capabilities is difficult and it does not lead to creation of any power imbalance (like the demonstration of nuclear weapon capabilities) and thus hardly serves any purpose for hard power. Presently, the success of the private entities like SpaceX and their ambition towards undertaking a human Mars mission is quickly changing global perceptions about technology leadership.

The Mars policies of all four nations are focused on science and human exploration. It is often argued that the probable spinoff technologies emerging from such missions could offer advantages for the militaries, but it would be foolhardy to believe that countries like the US and China would have to go all the way to Mars to modernize their armed forces! Theoretically, an arms race is about positioning of a nation alongside its advisories by continuously increasing its own military resources. It would also involve demonstrating its technological superiority in the strategic domain. Nations would go to Mars only when they have clarity about their scientific focus and have capacity (both technical and economic) to develop spacecraft for such purposes. It is highly unlikely that, in the 21st century, nations will race against each other to conquer Mars.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.