Semantics in lexicon: Moving away from the term “salvage” in outer spaceby Michael J. Listner

|

| The idea of salvage in outer space is misunderstood and mischaracterized by private space enthusiasts. |

However, the idea of salvage in outer space or, more specifically, the term “salvage,” is cringe-worthy as the idiom tends to relate to maritime law and practice and not outer space. In particular, the international framework for outer space is not congruent with salvage in the maritime domain and this contrast creates confusion when the term salvage is brandished about for outer space. What is required is a new expression for this activity in outer space. However, before discussing a new paradigm, let’s review the three types of salvage in maritime law: the law of finds, pure salvage, and contract salvage.

Law of finds

The law of finds is often conflated with salvage but is not really salvage. The point of salvage in the context of maritime law is to encourage persons to render prompt, voluntary, and effective service to ships at peril or in distress by assuring them compensation and reward for their salvage efforts. Rather than obtaining title to the salvaged property, a salvor acts on behalf of the property’s owner, thereby obtaining a security interest or lien against the property saved.[2] The law of finds on the other hand, allows a finder of abandoned property to acquire title by reducing the property to personal possession.[3] Aside from this contrast with salvage, the idea of a “law of finds for outer space” would be inconsistent with Article VIII of the Outer Space Treaty and consequently a non-starter as the jurisdiction of the state that launched the space object remains in perpetuity.[4]

Pure salvage

Pure salvage is a voluntary service rendered to imperiled property on navigable waters where compensation is dependent upon success, without prior agreement or arrangement having been made regarding the salvor’s compensation.[5] Pure salvage relies does not involve bargained for legal detriment, i.e. consideration, and relies up the legal theory of quantum meruit, which simply means “as much as deserved”, and measures the recovery under an implied contract to pay compensation as the reasonable value of services rendered.[6] However, pure salvage in the maritime context, like the law of finds, is incompatible with obligations under international law as interfering with a space object would violate the rights of the state that launched it.[7]

Contract salvage

Contract salvage is a service entered into between the salvor and the owners of the property in jeopardy and involves the law of contracts and bargained for legal detriment, i.e. consideration. The contract may be made by the parties or their agents pursuant to a written or oral agreement and fixes the amount of compensation to be paid. Also, dissimilar to pure salvage, contract salvage may specify payment for whether the salvage operation is successful or not.[8]

| Conflating the maritime concept of salvage with activities in outer space involving space objects is awkward at best and inappropriate at worst. |

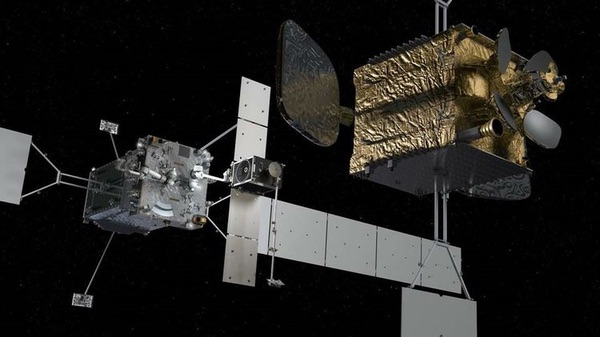

Unlike pure salvage and the law of finds, contract salvage is viable as a space activity, and the aforementioned operations of SpaceLogistics’ MEV-1 and MEV-2 spacecraft indeed represent a form of contract salvage. However, the idea of salvage is intrinsically linked to the maritime domain and maritime law, which is dissimilar to outer space and its legal framework. Therefore, the two must be separated.

Separating maritime law from space law

Space law is an evolving area with the discipline transitioning from a strictly international focus to one that includes domestic law and practice. Regardless, the roots of space law lie in international law, and the propensity is to analogize outer space and space law as part of the global commons along with terrestrial domains, e.g. the oceans the atmosphere and Antarctica.[9] Indeed, the foundations of international space law and the Outer Space Treaty in particular have been compared to Antarctica in the course of litigation,[10] and more often than not it is the maritime domain and law that is linked to outer space and the field of space law. This leads to the concept of maritime salvage and the law of finds being confused with salvage as an outer space activity.[11] Nevertheless, the outer space environment is not part of the global commons and disparate from the terrestrial domains, which necessitates the legal approach to outer space be tailored for the exceptionality of that domain.

Therefore, conflating the maritime concept of salvage with activities in outer space involving space objects is awkward at best and inappropriate at worst. As outer space activities such as rendezvous and servicing operations are on the cusp of becoming a routine non-governmental space activity, it is time to address the legal concept of “salvage” in outer space by starting with the lexicon to differentiate these activities from their maritime roots and tailor it for the outer space domain; specifically, to create a legally recognized non-governmental outer space activity.

Reclamation, not salvage

Choice of words have effect, especially in the legal context. Using the term salvage for outer space links the maritime activity of salvage and the law of finds, which is inconsistent with the fundamentals of space law, to outer space. Dipping into the thesaurus lends itself to a solution that separates the concept of salvage from the maritime domain to create a distinctive term appropriate to outer space. That word is reclamation.

Reclamation finds its root in the word “reclaim”, which The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “as the act or process of reclaiming…”[12] Subsequently, “reclaiming” is defined in part as “to rescue from an undesirable state…” or to “to obtain from a waste product or by-product…”[13]

Given this definition in the standard treatment of the word reclamation and its root reclaim, the term reclamation provides a foundation to classify outer space activities similar in scope to what occurs in contract salvage that can be tailored for the outer space legal framework and, concurrently, be detached from maritime legal structure and nomenclature to become a licensed outer space activity.

| Rechristening salvage as reclamation for outer space will sever the bonds from terrestrial analogies and provide the foundation for a unique activity for outer space. |

Accomplishing this requires a legal act to breath the activity of reclamation into existence, define its characteristics, and create a legal authorization consistent with international law. There are two approaches: a legally binding treaty or domestic space legislation. As the former has fallen out of favor for outer space and unlikely to materialize anytime soon, the latter is the prudent course to take. This puts the onus on Congress to take the existing international legal framework and pass legislation that creates a licensed non-governmental activity that permits space object reclamation.

The Space Object Reclamation Act

The Space Object Reclamation Act is a bottom-up, legislative solution to create a privilege in a non-governmental outer space activity that breaks with the maritime concept of salvage. While this essay will not offer a complete draft of the legislation, it offers some key language the Act would enunciate in two key areas.

First, the Act would define reclamation, which might go along these lines:

“Reclamation: The act by a non-governmental entity of recovering, repairing, servicing or relocating a space object located outside the terrestrial environment.”

Second, the Act would create the right to perform reclamation and direct the appropriate federal agencies to provide authorization.[14]

“A non-governmental entity under the jurisdiction of the United States will be permitted to perform reclamation on space objects registered to the United States.

The federal agency or agencies responsible for licensing non-governmental space activities shall recognize the activity of reclamation and authorize the activity of reclamation subject to the Code of Federal Regulations and amend regulations as necessary to accommodate the activity.

Federal agencies responsible for licensing of spectrum and remote sensing shall recognize the activity of reclamation and license the necessary spectrum and remote sensing permits accordingly.

To the extent the activity of reclamation involves a space object not registered to the United States, the activity of reclamation may only be performed with the permission of the state to whom the space object is registered to and the permission of the Department of State.

The Secretary of State in coordination with the Secretary of Defense and the primary authorizing agency shall create a mechanism through which approval of reclamation activities performed on space objects belonging to another state maybe facilitated taking into account national security interests and export control regulations.”

This, of course, is rough language. However, it provides a baseline to legislate the activity of reclamation. The Space Object Reclamation Act will clear the fog surrounding rendezvous and servicing activities and pave the way for further efforts to address orbital debris, facilitate the development of a cislunar economy, and lessen tensions regarding whether these activities are disguised anti-satellite tests or operations.

Conclusion

Rechristening salvage as reclamation for outer space will sever the bonds from terrestrial analogies and provide the foundation for a unique activity for outer space. Furthermore, enacting the Space Object Reclamation Act, or legislation similar to it, will eliminate the nebulous characteristics of a non-traditional space activity involving the recovery, repair, servicing, or relocating of space objects in orbit, and encourage non-governmental entities to innovate and contribute to STEM education. Moreover, reclamation as an activity, which is consistent with the Outer Space Treaty, will build upon and amplify the existing international framework and jurisprudence of space law. However, unless and until Congress decides to take up the Space Object Reclamation Act or a similar bill, the confusion over salvage and outer space will continue, and stunt the growth of the outer space economy.

Endnotes

- The Westar VI communication satellite was launched on the same space shuttle mission and likewise failed to reach GEO. Palapa B2 was registered originally as 1984-011D and listed as “recovered” in the UN Registry of Space Objects and listed as registered to Indonesia. After launch Palapa B2 was re-designated Palapa B2R and registered as 1990-34A and registered to the United States. he planned salvage mission similarly involved Westar VI. There was much work to be done by Hughes prior to the space shuttle mission to recover the satellites to make them retrievable. A good account of the salvage mission can be found on a Hughes history website.

- See R.M.S. Titanic, Inc. v. The Wrecked & Abandoned Vessel, 742 F.Supp.2d 784, 793 (E.D.Va. 2010)

- See Id.

- “A State Party to the Treaty on whose registry an object launched into outer space is carried shall retain jurisdiction and control over such object, and over any personnel thereof, while in outer space or on a celestial body. Ownership of objects launched into outer space, including objects landed or constructed on a celestial body, and of their component parts, is not affected by their presence in outer space or on a celestial body or by their return to the Earth. Such objects or component parts found beyond the limits of the State Party to the Treaty on whose registry they are carried shall be returned to that State Party, which shall, upon request, furnish identifying data prior to their return.” The Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, Jan. 27, 1967, 610 U.N.T.S. 205, art. viii.

- See New Bedford Marine Rescue, Inc. v. Cape Jeweler’s Inc., 240 F.Supp.2d 101 (D. Mass. 2003) at Footnote 1, citing 3A Martin J. Norris, Benedict on Admiralty § 159 (2002)

- Kintz v. Read, 626 P.2d 52, 55.

- See Outer Space Treaty, art. viii.

- See New Bedford Marine Rescue, Inc. v. Cape Jeweler’s Inc., 240 F.Supp.2d 101 (D. Mass. 2003) at Footnote 1, citing 3A Martin J. Norris, Benedict on Admiralty § 159 (2002).

- Outer space as a global commons is held to be a tenet of international law; however, it still elicits much debate as its standing as international law is challenged by domestic policy that asserts the opposite. The latest iteration of that opposition is found in Executive Order 13194, which restates the US position space is not a global commons, rejects the Moon Agreement and reinforces US domestic space law on space resources.

- The D.C. Court of Appeals addressed this in Beattie v. United States, 690 F. Supp. 1068 (D.D.C. 1988).

- The law of finds allows a finder of abandoned property to acquire title by reducing the property to personal possession. See Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc. v. Unidentified, Wrecked and Abandoned Sailing Vessel, 727 F.Supp.2d 1341, 1344 (M.D.Fla. 2010) at Footnote 1, citing 3A Martin J. Norris, Benedict on Admiralty § 159 (2002).

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary available here.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary available here.

- The author’s use the word “right” is not intended to mean a fundamental right, which is protected by the Constitution. Precisely, the word “right” as used in this sense means privilege as it is the opinion of this author the right for non-governmental space activities lies with the state per Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.