From development to operations, at long lastby Jeff Foust

|

| “The big milestone here is that we are moving away from development and test into operational flight,” said Bridenstine. |

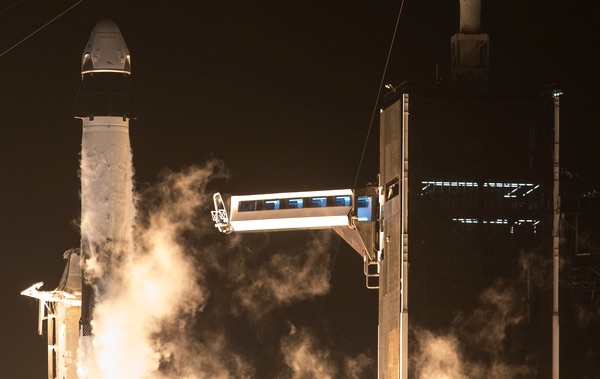

On Sunday night, all eyes were on the Falcon 9 rocket that lifted off from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A. Atop that rocket was a SpaceX Crew Dragon spacecraft with four astronauts from NASA and the Japanese space agency JAXA on board. That spacecraft is scheduled to dock with the International Space Station Monday night, delivering those astronauts for a six-month stay on the station.

There were plenty of firsts associated with the launch, from the first capsule to carry four people to the first Black astronaut, Victor Glover, to fly a long-duration ISS mission and the first Japanese astronaut, Soichi Noguchi, to fly to orbit on three different spacecraft (Space Shuttle, Soyuz, and Crew Dragon.) Most importantly, though, it was the first “operational” commercial crew mission, beginning a regular series of flights that fully restores U.S. human orbital spaceflight capability.

“The big milestone here is that we are moving away from development and test into operational flight,” Jim Bridenstine, the NASA administrator, said during a post-launch press conference Sunday night.

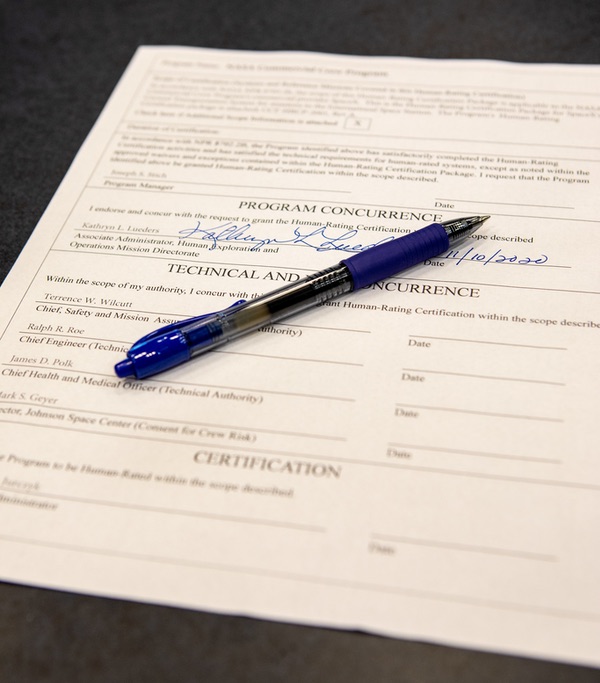

In the long run, then, the biggest milestone of the week may not have been the brilliant nighttime launch from LC-39A, but a piece of paper signed in a conference room at KSC five days earlier. At the end of the flight readiness review for the Crew-1 mission, NASA officials signed documents formally certifying the Crew Dragon spacecraft to carry NASA astronauts, ending the development phase of the spacecraft.

“It’s NASA saying to SpaceX you have shown us you can deliver a crew transportation capability that meets our requirements,” explained Kathy Lueders, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations, during a briefing last Tuesday after the completion of the review. Lueders had managed the commercial crew program for six years before being promoted to associate administrator in June. “It’s just a tremendous day that is a culmination of a ton of work.”

“It’s very exciting to us get past this milestone and have the agency approve our human rating certification,” said Steve Stich, current manager of the commercial crew program, at that briefing.

The Human Rating Certification Plan document for SpaceX’s Crew Dragon spacecraft, signed November 10 by NASA’s Kathy Lueders. (credit: NASA/Cory Houston) |

NASA felt the milestone important enough—and perhaps in danger of being overlooked amid all the attention about the launch itself—that it held another briefing two days later with Phil McAlister, the director of commercial spaceflight development at NASA Headquarters. “With this milestone, NASA has concluded that the SpaceX system has successfully met our design, safety and performance requirements,” he said. “It marks the end of the development phase of the system.”

| “We did what we said we were going to do, which was prioritize safety,” McAlister said. “We were not a schedule-driven program. We were a safety-driven program.” |

That development phase lasted a decade, dating back to the original Commercial Crew Development, or CCDev, awards made by NASA in 2010. (SpaceX did not get one of those CCDev awards, which only had a combined value of $50 million, but did join the program in 2011 with a $75 million CCDev2 award.) That development took far longer than projections at the start of the program, when NASA expected spacecraft to enter service in 2015 or 2016.

“In the aerospace industry we like to have aggressive schedules. That keeps the team focused, that keeps the team motivated,” he said. “We did have an incentive to get done with development because we wanted to make sure that we again had US access to space.”

One reason for the delay was a shortfall in funding in the early years of the program, with members of Congress skeptical that companies could develop crewed spacecraft under this new commercial approach, despite the successes being demonstrated at that time under the commercial cargo program. Technical problems, like those in almost every other major space project, also delayed development.

McAlister said the delays in the commercial crew program had the benefit of demonstrating the agency’s commitment to safety. “In the very beginning, the big debate was, are we going to be able to move into this public-private partnership model and maintain safety as the priority for commercial crew?” he said. “We consistently incorporated safety as the number one priority in the commercial crew program.”

That emphasis on safety took priority over schedule. “We did what we said we were going to do, which was prioritize safety,” he said. “We were not a schedule-driven program. We were a safety-driven program.”

With SpaceX’s development of Crew Dragon complete, some at NASA have declared the spacecraft operational. “We’re launching what we call an operational flight to the International Space Station,” Bridenstine said Friday.

McAlister, though, wasn’t as certain. “I would not characterize it as ‘operational’ at this point. There a little bit of a debate as to when we will achieve that designation,” he said. “We’ve completed the development phase and we are transitioning into operations.”

“We don’t want to ever just declare victory and say we’re done learning and get complacent,” he continued. “There’s a feeling that, if we start just referring to these as operational, that we won’t stay hungry, we won’t remain vigilant. I am very sensitive to that issue.”

Bridenstine acknowledged that at the post-launch briefing. “We use the word ‘operational’. Make no mistake, when you’re flying into space, there’s always risk and we will always be diligent,” he said.

The Falcon 9 for the Crew-1 mission at sunrise the day of launch November 15. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

The commercial crew development effort is not over. Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner remains a work in progress after an uncrewed test flight 11 months ago suffered problems that forced an early end to the mission. Boeing later announced it would fly a second uncrewed test, called Orbital Flight Test 2, which it had hoped to launch this year.

That won’t happen. “The pacing item is getting the software ready to go,” Stich said at last week’s briefing. “Right now, the earliest we would go fly that flight would be the first quarter of next calendar year.” That would be followed no earlier than next summer by a crewed flight test with three NASA astronauts on board.

The delays Boeing has suffered vindicated a decision in the early days of the program to go with two companies despite budget pressures that led some in Congress to call on NASA to select only one company. Having the two companies, McAlister said, means that NASA will soon “a redundancy in this capability that we have never had before.”

| “We use the word ‘operational’. Make no mistake, when you’re flying into space, there’s always risk and we will always be diligent,” Bridenstine said. |

“They are very different companies. They have different cultures, different ways of going about doing business. I wouldn’t say one is better than the other. They’re just different,” he said of Boeing and SpaceX. Boeing, he explained, spends more time on analysis, while SpaceX focuses more attention on testing. “There’s no one right answer for this. They’re both very good.”

Having two companies able to transport people to and from low Earth orbit fits into NASA’s broader vision of LEO commercialization that includes development of commercial space stations to eventually succeed the ISS (see “A dynamic ISS prepares for its future, and its end”, The Space Review, November 2, 2020.) That will, in turn, allow NASA to focus more resources on exploration beyond Earth orbit, even if the plans for the Artemis program change under the incoming Biden Administration.

“I believe that we are about to see a major expansion in our ability to work in, play in, and explore space,” McAlister said. “People have been predicting this for decades, and I hope we are on the cusp of seeing that happen.”

“Now that we have the capability to fly all types of people to space, not just government astronauts, more people are going to want to go,” he continued. “They’re going to think of new things to do and make in space, which will in turn is going to attract even more people who want to fly, and they will think of new things to do. I believe it is going to be a virtuous, self-reinforcing cycle that will greatly expand our presence in space.”

McAlister noted that was the aim of the commercial crew program when it was being developed at NASA a decade ago, reading an excerpt from the plan NASA delivered to the White House about it: “Partnering with industry in this innovative way potentially accelerates the availability of US human access to low Earth orbit as well as reduces the risk of relying solely on foreign crew transports to the ISS for years to come. It will also strengthen the US commercial space launch industry, encourage competition, act as a catalyst for the development of new space markets, provide new high technology jobs, and reduce the costs of human access to space. The commercial crew program promises to transform human spaceflight for future generations.”

“I am extremely proud that NASA has been able to successfully deliver on those promises made to the American people a decade ago,” he said.

Delivering on those promises—by NASA as well as by SpaceX—and opening a new era of commercial human spaceflight was something that was achieved by a launch Sunday, but also from a decade of work that led up to the signing of a document five days earlier.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.