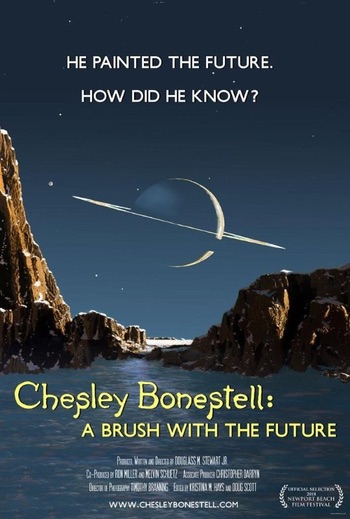

Chesley Bonestell and his vision of the futureby Jeff Foust

|

| The actual lacked the jagged mountains that were one of his trademarks. (Bonestell, in archival footage, remarked that the actual appearance of the Moon was “a great disappointment” to him.) |

While Bonestell is known now for his space artwork, that wasn’t what he was known for during much of his life. Born in San Francisco in 1888, he was interested in art from an early age, including paintings of Saturn inspired by viewing the planet at the Lick Observatory in 1905. However, he went on to study architecture, helping in the design of buildings while working in San Francisco, London, and New York. That included work on the Chrysler Building in Manhattan and the Golden Gate Bridge; drawings of the latter were in storage at the bridge’s headquarters building for decades until rediscovered by another designer.

Bonestell’s career then turned to the stars—Hollywood, that is. He worked as a special effects matte painter on movies like The Hunchback of Notre Dame and Citizen Kane. However, in his spare time began working on the space paintings that would make him famous, starting with a set of landscapes on the moons of Saturn published to great acclaim in Life magazine in 1944. His visions of space, and our future of space, soon were in high demand for magazines, books, and movies.

The movie includes interviews with a wide range of people, including artists and engineers inspired by Bonestell to pursue their own artwork or to make the visions in Bonestell’s pieces become reality. That reality turned out a little different from his art, from the design of the rockets to a lunar landscape that lacked the jagged mountains that were one of his trademarks. (Bonestell, in archival footage, remarked that the actual appearance of the Moon was “a great disappointment” to him.)

The film never really explains why Bonestell, after a long career in architecture and movies, made the shift to painting distant worlds and rocketships. The seed for doing so was planted in that trip to Lick Observatory decades earlier, but why it took so long to germinate, and why it finally did after decades drawing buildings and bridges, and painting landscapes for film sets, is less clear. Fortunately, it did, and Bonestell continued to paint until his death in 1986.

Neither the future nor the solar system turned out quite like what Bonestell depicted, but no prognosticator is 100% accurate. His art did offer a realistic vision of what space exploration could be like just as spaceflight was at the cusp of becoming reality—and, in the process, helping enable that reality in a small way.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.