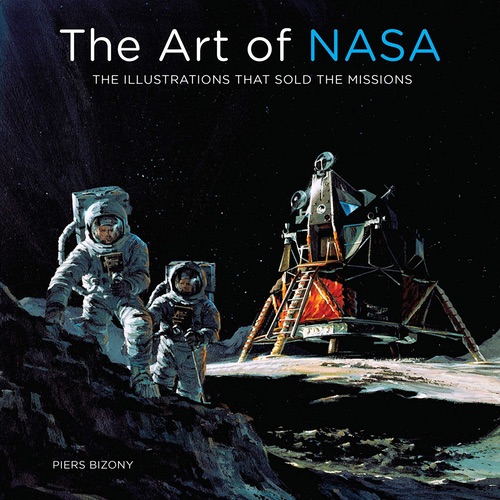

Review: The Art of NASAby Christopher Cokinos

|

| Whether in vivid, almost garish colors or in subdued monochromatic hues, these paintings are largely retrofuturist visions of the technological sublime. |

The book’s popular culture focus complements long available compendia from the famous NASA Fine Arts program, such as NASA/ART: 50 Years of Exploration and the earlier, massive Eyewitness to Space, both from publisher Harry N. Abrams, with their requisite Norman Rockwells and Robert Rauschenbergs. In fact, there is a bit of overlap between the world of aerospace illustration and high-end art with such figures as Robert McCall and, more recently, Joanna Barnum, whose watercolors of the James Webb Space Telescope are included in The Art of NASA as are several iconic McCall paintings.

The book really shines in presenting work by relatively unknown and even anonymous painters and illustrators who worked for the space agency or corporate contractors. In The Art of NASA I discovered artists I didn’t know, including John Carr of Bell, Martin Marietta engineer and painter Charles Bennett, and Los Angeles Times art director Russ Arasmith. These and other artists presented cut-away views of spacecraft, dramatized spacewalks and Moon landings, and provided iterations of spacecraft design, especially as the Space Shuttle evolved due to budget and political considerations. Whether in vivid, almost garish colors or in subdued monochromatic hues, these paintings are largely retrofuturist visions of the technological sublime.

Consider one spread showing three versions of the same scene: the ascent of the Apollo Lunar Module from the Moon’s surface. Arasmith’s black-and-white view is a low-angle shot, strongly vertical, so that the LM rises just under the globe of Earth. It is a vision of power and majesty. Pierre Mion’s National Geographic illustration is dominated by a high-angle view downward of the LM rising from a largely gray-brown surface, the only significant colors being the flag and the descent module’s patches of gold foil. The view portrays science packages, discarded space suits, an instrument cable, and astronaut tracks looking vaguely like Percival Lowell’s maps of Mars. The downward look renders the action already a memory. Between these two depictions is Carl Zoschke’s low-angle 1964 illustration with a purple-tinged starry sky, icy blue Moon rocks and impossible alpenglow on jagged peaks. Even the LM’s exhaust is green. A crescent Earth hangs low. It’s like something out of an Italian sci-fi flick. All three incorrectly show exaggerated exhaust and flame effects. All three fail to show the rounded, highly pocked ruggedness of the Moon. Yet, they inspire. That was their point, of course. The claim to realism was always hedged in favor of sublime emotion. Now they function as a docking mechanism to nostalgia and a visual history of rocket dreams put into imaginative action.

Zoschke, in particular, presents dramatic, sometimes even post-surrealist work, as in his gorgeous view of Lunar Landing Research Vehicle; here, the gold-limbed, gangly craft with its Plexiglass open cockpit protects the Earth-bound astronaut—for the LLRV was a training craft, a rather dangerous one. Zoschke has the vehicle flying over a flat black plain incised with parallel lines receding toward sharp blue peaks and an industrial complex presumably in California. Above the scene a dark, early model Lunar Excursion Module descends, and an impossibly huge Moon looms in a blue-black, starry sky. The visual elements make an argument for how the foregrounded LLRV, pitching upward into flight, will lead the astronauts to the landing to be made by that symbolic LM on that huge Moon, all of which is coordinated by the technicians housed in a West Coast factory whose mountains might be like those in the sky. It’s a beautiful and brilliant work.

McCall was a master at this kind of visual argument, and his work here—seen before—seems to be in conversation with Zoschke. Other artists take a more informational approach, especially in cutaway illustrations, where we see cosmonauts and astronauts meeting in space for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Mission or, in a realist mode, when we peer over the shoulders of two shuttle crewmembers supervising station construction outside their windows. In Bruce Morser’s 1990 illustration, multiple space station elements are combined in cutaway views and almost swarm the eye with their complexity. In a recent Lockheed digital illustration, we see the interior of the planned Lunar Gateway in another cut-away. Other approaches also combine inspiration and information, as in a Lou Nolan painting of Pioneer 10 foregrounded against its red line trajectory and the planets with their blue-green orbital lines.

| The claim to realism was always hedged in favor of sublime emotion. Now they function as a docking mechanism to nostalgia and a visual history of rocket dreams put into imaginative action. |

Organized chronologically, The Art of NASA largely focuses on crewed space missions, from Mercury to the International Space Station onward to plans for 21st century human landings on the Moon and Mars. Though the book includes robotic solar system probes and space telescopes, I would have welcomed more such illustrations in the chronology, from Explorer to TIROS to Mariner and more. These are not covered and suggest another book yet to be done.

The biggest drawback are the prose introductions to each section, which, while sufficient for a general reader, won’t add much to a space fan’s knowledge. I was disappointed not to have any artist biographies, thorough discussion of techniques (especially given the book’s thoughtful consideration of how ephemeral this kind of graphic work is) or analysis of how the illustrations function as visual rhetoric. We get little sense of how widely seen many of the images may have been.

While lacking the kind of thorough contextual commentary that one finds in, for example, Another Science Fiction: Advertising the Space Race: 1957-1962, Bizony’s book is clearly a labor of love by an esteemed space writer. Its critical weaknesses may merely point to the need for serious art-historical scholarship about NASA and aerospace art that continues to serve a propagandistic purpose.

These matters aside, The Art of NASA is a must-have book. The work is varied, often sentimental, uplifting and, near the conclusion, pointed toward the near-term future. This visual spectacle will give hours of pleasure to those who care about space exploration. It is already a favorite of mine.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.