The future of Mars exploration, from sample return to human missionsby Jeff Foust

|

| “We unanimously believe that the Mars Sample Return program should proceed,” said Thompson. |

Just how those samples will be returned, though, is still a work in progress. NASA and ESA have agreed to cooperate on the effort, proposing a pair of missions launching as soon as 2026: a NASA-led lander with an ESA “fetch rover” to collect the samples, load them into a rocket, and launch them into orbit; and an ESA-led orbiter with a NASA collection system to pick up the samples and return them to Earth. It’s a complex, expensive effort, but one for which there appeared to be growing consensus about how to accomplish.

A recent report, though, suggested that those plans might be a little too ambitious, in that it may take more time, and more money, than originally envisioned. That reality check comes as other elements of future Mars exploration, including both robotic and human missions, start to take shape and face similar scrutiny.

After the successful launch of Mars 2020, NASA announced it would conduct an independent review of its Mars Sample Return program. The purpose of the review was to examine the plans as they currently stood to identify problems while the program was still in its early phases.

“The goals of the review are to make sure we’re on a firm foundation technically going forward, to review the concepts that have been developed to date, and also to look at the cost and schedule that we’re proposing and to make sure that they agree that we’ve got the right resources we need to do this job,” Jeff Gramling, Mars Sample Return program director at NASA, said when the review was announced in mid-August.

That review would move quickly. Less than three months after announcing the review, NASA released the independent review board’s final report. The good news for NASA was that the panel found no show-stoppers with the overall program.

“We unanimously believe that the Mars Sample Return program should proceed,” said David Thompson, the former CEO of Orbital ATK who chaired the board, in a call with reporters November 10. “We think its scientific value would be extraordinarily high.”

Or, in the words of another board member, planetary scientist Maria Zuber of MIT, “Full steam ahead.”

The bad news, though, was that Thompson’s board concluded that plans for carrying out the two future launches—the Sample Return Lander and Earth Return Orbiter—were unlikely to remain on schedule.

“Since the current development schedule necessary to achieve the 2026 launches were judged by the IRB [independent review board] to not be compatible with recent NASA experience,” Thompson said, “we believe NASA should replan the program for launches in 2027 and 2028.” The lander would, in that scenario, slip to 2028, while the orbiter could launch in either 2027 or 2028, depending on the selected trajectory.

A delay in launch, not surprisingly, comes with an increase in cost. NASA had said little about how much future phases of Mars Sample Return would cost, beyond rough estimates of $2.5–3 billion. (That does not include Mars 2020, which costs $2.7 billion through its first Martian year of operations after landing, nor ESA’s contribution of about $1.8 billion.) But the independent review board concluded those phases of Mars Sample Return will likely cost $3.8–4.4 billion.

The panel said NASA should investigate other changes to the mission design. One possibility is to split the Sample Return Lander into two landers: one carrying the fetch rover and the other the rocket for launching the samples into orbit. A two-lander approach, the report stated, “may open up increased margins and design flexibility, [and] enable greater use of already-developed systems and subsystems.”

| A decision on the schedule for the Mars Sample Return program, Zurbuchen said, could come “on the timescale of a year or so.” |

That lander, and the fetch rover, are designed to be solar powered, but the report said NASA should consider adding an RTG like that powering Mars 2020 to the lander. Doing so, it argued, could extend its lifetime on the surface and improve thermal conditions, particularly for the Mars Ascent Vehicle rocket.

NASA accepted many of the recommendations from the independent panel, but stopped short of endorsing a delay in the 2026 launch of the orbiter and lander missions. Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator, said any decision on changing schedules would require working with stakeholders in both the US and Europe. A decision on the schedule for the program, he said, could come “on the timescale of a year or so.”

The report noted there are other risks should the mission be delayed beyond 2028: a 2030 launch would force the lander to operate during dust storm season on Mars. “It makes the mission more complicated, potentially requiring a redesign of the elements,” said Gramling.

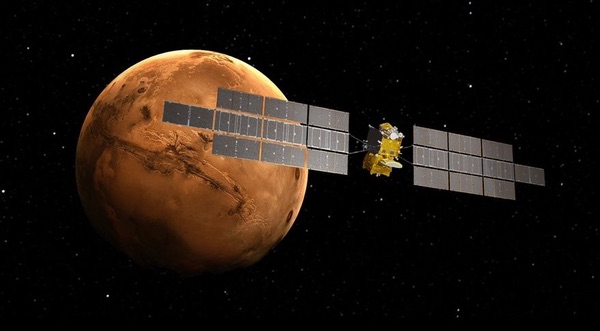

For now, work continues on Mars Sample Return activities towards a 2026 launch on both sides of the Atlantic. In October, ESA awarded a contract to Airbus Defence and Space to develop the Earth Return Orbiter valued at €491 million (US$595 million), part of a set of awards that Airbus and Thales Alenia Space received to support ESA’s contributions to lunar and Mars exploration.

The Earth Return Orbiter will use electric propulsion to maneuver into and out of orbit around Mars, collecting samples that will be returned to Earth. (credit: Airbus) |

Mars Sample Return is the major robotic Mars mission of the coming decade for NASA, but it is not the only one. The fiscal year 2021 budget proposal introduced a new one: Mars Ice Mapper, an orbiter equipped with a synthetic aperture radar designed to search for subsurface deposits of ice.

The inclusion of Mars Ice Mapper in the budget surprised some in the scientific community, who had not proposed such a mission. Instead, Mars Ice Mapper came out of the human exploration part of NASA as a precursor to support later human missions to Mars.

The mission was the outcome of a “summer study” in 2019 by the agency, said Jim Watzin, the former director of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program who now serves as a senior advisor supporting human Mars mission planning at the agency. “The purpose of the summer study was to pull together NASA’s strategy for preparing for human exploration,” he said, including both the Moon and Mars.

A key element of that was identifying subsurface ice deposits that could be studied, and utilized, by those crewed missions. “The obvious question was, ‘Where?’ Where does the crew have to land?” he said at a November 23 meeting of a panel supporting the ongoing planetary science decadal survey. “So, the Mars Ice Mapper mission was identified as an essential precursor mission necessary to get that critical information so we could decide where to go for the first human mission, and also how to prepare for that mission.”

| “This is an exploration precursor mission. It’s not a science mission per se,” Watzin said of Mars Ice Mapper. |

NASA envisions Mars Ice Mapper as an international endeavor. The primary instrument, the radar mapper, would come from the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). The Japanese space agency JAXA would provide the spacecraft bus and Italian space agency ASI the communications subsystem for the spacecraft. Those arrangements could be formalized as soon as this month with a “statement of intent”, followed a memorandum of understanding in the spring or summer of 2021.

NASA would serve as the mission coordinator for Mars Ice Mapper and also provide a launch, likely no earlier than 2026. Watzin said NASA’s notional budget for the mission is just $185 million, not including the contributions from international partners.

The spacecraft would operate in a low sun-synchronous orbit around Mars, using an L-band radar to probe to depths of five to seven meters, said Jim Garvin, chief scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, at the decadal survey panel meeting. “This particular approach, as a point solution for Ice Mapper, has been peer reviewed by five experts from the radar community who have all flown radars in space,” he said, who concluded it meets the goals of looking for subsurface ice deposits.

NASA wants to fly Mars Ice Mapper in 2026 or 2028. “We really need this data by the 2030 timeframe,” said Rick Davis, assistant director for science and exploration in NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in order to support a human mission notionally in the mid-2030s.

However, some Mars scientists have been critical of the mission. At the decadal survey meeting, as well as one a week later by NASA’s Planetary Science Advisory Committee, some questioned how the mission could meet goals of the science community.

“This is an exploration precursor mission. It’s not a science mission per se,” Watzin said at the decadal survey meeting. He compared it to Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which NASA developed initially to support the Constellation program of human lunar exploration more than a decade ago, but later became part of NASA’s planetary science program.

“The notion of an exploration-driven mission that produces huge science returns is not without precedent,” said Tim Haltigin, senior mission scientist for planetary exploration at CSA, also citing LRO.

The focus of the beginning of the Mars Ice Mapper mission, he said, will be the top-level reconnaissance objectives, “closing those knowledge gaps as quickly as we can to inform the future human exploration planning.” In a later phase of the mission the focus would turn to science: “make the platform available for science investigations moving forward.”

NASA officials also noted that the mission will be run by NASA’s science division, but funded by human exploration, so that if Mars Ice Mapper didn’t go forward, the funding would not be available for alternative Mars missions. “If, for whatever reason, we didn’t do Ice Mapper, that money is not available to us,” said Eric Ianson, director of the Mars Exploration Program, at the Planetary Science Advisory Committee meeting. “This is funding specifically identified by the agency in support of exploration.”

The discussions at those meetings about Mars Ice Mapper revealed details about a complementary effort. One challenge of a mission like Mars Ice Mapper is that radar instruments generate huge volumes of data, making it difficult to get it back to Earth.

One solution is for the mission to relay data through dedicated communications satellites, developed and potentially operated commercially. “Experimenting with commercial communications was brought up as an opportunity as we examined the bandwidth limitations of Ice Mapper,” Watzin said, noting the sophistication of commercial communications satellites orbiting Earth today. “Is the time right that one could exploit the derivation of that technology and deploy it Mars at an affordable cost such that we can make a paradigm shift in how we do communication and increase the effectiveness of how we do our missions?”

| A relay network could increase the amount of data Mars Ice Mapper could return by two orders of magnitude. “That is revolutionary, potentially,” Davis said. |

The idea of having a dedicated communications satellite system is not new. In the early 2000s, NASA studied a Mars Telecommunications Orbiter that would relay data between Earth and other spacecraft orbiting or on the surface of Mars. The agency didn’t proceed with that mission, instead relying on orbiters primarily intended to do science to serve as relays for missions on the surface.

NASA revisited the concept several years ago with the Next Mars Orbiter, or NeMO, which would serve as a communications relay and also carry a high-resolution camera, serving as a successor to the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. That proposal, too, was set aside in favor of using existing, if aging, orbiters as relays.

The new concept differs from earlier one in both technology and procurement. One concept discussed at the recent meetings involved three satellites in orbits 6,000 kilometers above the surface. The satellites would be able to communicate with Mars Ice Mapper and potentially other missions in orbit and the surface, relaying their transmissions to Earth. Those satellites could also have laser intersatellite links between each other.

Davis said such a system could increase the amount of data Mars Ice Mapper could return by two orders of magnitude. “That is revolutionary, potentially,” he said.

NASA officials said they were looking at commercial approaches for the system. Davis noted that discussions about the communications network involved both NASA’s Space Communications and Navigation office as well as the commercial cargo and crew programs. “We are essentially trying to leverage their experience on how to do this very efficiently,” he said.

Studies of that network are still in their early phases, and NASA officials said that if it turns out to be infeasible in some way, they will proceed with Mars Ice Mapper without it. Those studies, though, have caught the attention of Congress, which mentioned it in a report accompanying the draft of the Senate’s version of a fiscal year 2021 spending bill.

“The Committee is aware that NASA is investigating possible new models for using commercial services for future communications with Mars surface assets in the late 2020s and early 2030s, though no such services exist today,” the report stated. It called for a study within 180 days of enactment “outlining the Science plan for securing such commercial services for future Mars surface assets.”

Mars Ice Mapper is part of a much broader effort to support the long-term goal of sending humans to Mars, no earlier than the 2030s. The agency is starting to plan exactly what that first mission would look like.

At a meeting last month of the Space Studies Board, Watzin discussed the status of the planning. “What grand questions could be addressed if were to join the power of man and machine at Mars that would be worthy of an endeavor of this nature?” he said. The answer to that, he said, “is to continue to expand the theme that has guided the Mars exploration science program for the last 20 years, which is follow the water.”

NASA now envisions that first human Mars mission be devoted to collecting subsurface water ice. “The objective of that mission that we’re now assessing is to return ice cores from that mission back to Earth for examination by the science community,” he said.

| The idea of sending humans to Mars to collect ice samples was underwhelming to some members of the board. “I find that argument very, very unconvincing,” said Elias. |

A reason for that goal, beyond the science benefits of collecting an ice sample, is that NASA is contemplating a relatively brief mission. “The first crewed mission to Mars is envisioned to be a short-stay mission, something on the order of 30 days or so,” he said. “What we’ve done with the ice cores is set a grand objective so we can start shaking out the requirements for the equipment and the conops [concept of operations] that would be necessary to support that.”

The idea of sending humans to Mars to collect ice samples was underwhelming to some members of the board. “I find that argument very, very unconvincing,” said Antonio Elias, a retired Orbital ATK executive, citing the advances in remote operations in mining and drilling on Earth.

Watzin argued that having humans on the surface would be more effective than remotely operated and autonomous systems. He added the mission would bring back “many, many tens of kilograms” of ice samples, including ice cores meters long. “When you look at how that’s done here on Earth, it is a marriage of crews of humans and equipment, both automated and manual.”

Others asked what other kinds of work astronauts would do on that initial, short mission. “Of course, there’s hundreds of things we would like to do over the course of time, as we continue to expand our stays and our capabilities at Mars,” Watzin said. “What we’re trying to do is identify a very challenging requirement as one of the driving things going into the mission architecture. We’ll see how that shakes out over the coming years.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.