Review: How to Astronautby Jeff Foust

|

| “But in all seriousness, by far, without a doubt, the most stressful thing I’ve ever done in my life was cut Samantha’s hair,” he writes. |

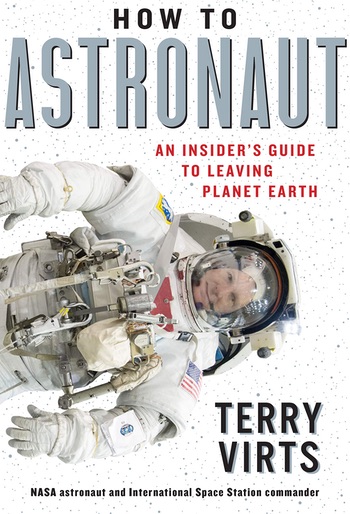

Former NASA astronaut Terry Virts also took a different path in his latest book, How to Astronaut. There’s plenty about his life and astronaut career in the book, but rather than a straightforward chronological approach, he offers a series of essays that offer insights on various aspects of the astronaut experience. “Not your typical astronaut fare,” he writes in the book’s introduction. “But as the saying goes, I’m not your typical astronaut.”

How to Astronaut includes more than 50 short essays, each on average five to six pages long, that are organized by theme, from “Training” and “Launch” to “Orbit” and “Re-Entry.” Each examines a particular part of the astronaut experience, like learning to speak Russian, the food available for space missions, and how to put on a spacesuit. He also describes photography from space, the subject of a book he wrote in 2017. That all sounds like basic material, but Virts provides that insider’s view of how things work—or, sometimes, don’t work.

Some of the anecdotes in the book are humorous. Virts recalls that, before his long-duration mission to the ISS, his crewmate, Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti, asked if he would cut her hair while in space, an effort that would involve extra training with her hairstylist in Houston. He did so twice during their 200 days in space, without incident. “But in all seriousness, by far, without a doubt, the most stressful thing I’ve ever done in my life was cut Samantha’s hair,” he writes. “Because if I’d screwed that up there would have been millions of Italians angry at me. And that’s probably not survivable.”

Other passages, though, are more serious. Virts discusses some of the occasional conflicts between crews in space and agency officials on the ground. One example was on the last of a series of spacewalks, when Virts said he and ground controllers had agreed not to do any additional “get-ahead” tasks if he finished ahead of schedule, given the “frenetic pace” of work on the spacewalks. Yet, when he wrapped up the planned work for that spacewalk early, he was asked to perform one such get-ahead task. He did carry it out, but after he returned he asked why it was added, and was told it came after a “fullblown conflict in mission control” between the flight director, who sided with Virts, and another official who asked for the task.

| “Not your typical astronaut fare,” he writes in the book’s introduction. “But as the saying goes, I’m not your typical astronaut.” |

Although Virts completed the task successfully and safely, he saw it as evidence of a broader problem. “If you make a decision and everything works out, it doesn’t mean you made the right decision,” he writes after describing an incident during training in the Alaskan wilderness where a group decided to ride out a storm. An example of the perils of that approach, he argues, was NASA’s decision to live with foam falling off the external tank, concluding it had not caused a problem on shuttle launches—until it did, tragically, on Columbia. He recalls feeling that loss personally, since he was one of the astronauts assigned to support the families of the STS-107 crew on that fateful mission.

Despite the seemingly practical nature of the book’s title, most people who read How to Astronaut won’t be looking for practical advice on how to be an astronaut. (Virts does include a chapter offering some tips for space tourists, such as taking any spacesickness medications offered, letting the providers handle the photography, and planning as much as possible what to do during the brief weightless experience on a suborbital mission.) But even for those who intend to remain on terra firma, Virts offers a behind-the-scenes look at the astronaut experience, and advice that transcends spaceflight itself.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.