A possible Biden space agendaby Roger Handberg

|

| The focus of US space policy will be upon space applications linked to climate change, as well as the continuation of human spaceflight, lunar first. |

The Artemis program, presently set for a first lunar landing in 2024, is also problematic due to budget issues. Congress supports the program but without the urgency the Trump Administration had demanded. Early signs are the program will continue if, for no other reason, than for the first time since the Constellation program in the George W. Bush administration a definite short-term goal is established. The return date accelerated to 2024 from 2028, but even if President Trump had been reelected, the reality was that timeframe was unrealistic since it assumed minimal or no delays. That is a heroic assumption, not typical of NASA programs since Apollo.

In this case, the Chinese concurrent push to go to the lunar surface possibly provides external political justification for the program’s continuation and a successful outcome of the return of American and partner astronauts to the Moon. The Biden Administration confronts an assertive Chinese leadership, meaning some response is required. Lunar landings are impressive and in themselves not threatening. Budget becomes the issue: there is not sufficient congressional support to keep the program on schedule for 2024 but perhaps sometime after that but prior to 2028.

The US Space Force moved quickly from a proposal pushed by several members of the House of Representatives to a presidentially supported initiative. Organizationally, a bureaucratic fait accompli is unlikely to be retracted especially, as more nations pursue establishing space commands and building antisatellite weapons. Whether weaponization of space occurs is unclear although less likely in a Biden administration, and more a response to others. Cost and heightened international instability reduce the incentive to deploy such weapons immediately.

All of the above are choices that the Biden Administration is unlikely to revise, except the National Space Council. This is dependent on the organization of the White House staff. In Democratic presidencies, science advisors have generally been central policy players, likely hostile to possible competitors no matter the narrowness of their remit. In the Trump Administration, there was no significant White House science advisor so space advocates were able to resurrect the National Space Council with Vice President Pence as chair. If the new science advisor is not hostile, the council could survive.

Future possibilities

The focus of US space policy will be upon space applications linked to climate change, as well as the continuation of human spaceflight, lunar first. Mars is outside the immediate framework of the Biden Administration—that becomes the story once the lunar missions have been successful. Congress lacks the willingness to appropriate sufficient funding to mount Moon and Mars programs simultaneously. There will not be any unofficial programs going to Mars, either, as most of the private space advocates plan innovative and large efforts but usually expect government money to fund their efforts.

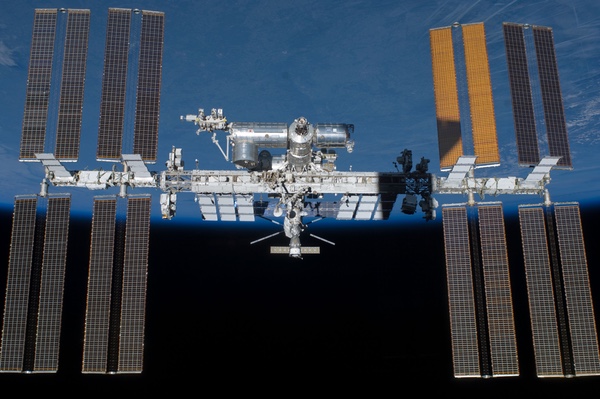

| A new space station provides another location from which commercial and scientific endeavors can operate. |

More critical steps forward could come if the Biden administration were to focus more energy and resources into two possibilities. Neither would likely be funded by the US government alone but may provide leadership and a framework. Resources would come from the United States, other nations, and the private sector.

First, the International Space Station (ISS) is currently projected to operate until 2030 or so, but the facility is aging with a successor not visible at this point. China’s space station is scheduled for 2022 but it is limited and not necessarily an improvement on the ISS except obviously newer and therefore more up to date. The Russians have proposed their new space station but its capabilities are unclear, particularly since the leadership talks of the space station not being permanently crewed.

A new space station provides another location from which commercial and scientific endeavors can operate. By starting the process of “ISS-2” development now, the new facility could incorporate multiple functions by designing those capabilities into the structure. The current ISS is the product of a lengthy, often-tortured development process which saw the number of functions or missions to be accomplished go from eight to two or three. This decline reflected NASA’s efforts to salvage a program constantly over budget and behind schedule.

This new effort would incorporate multiple players: other national partners, commercial interests, and the science community. Similar to the original space station concept, the new space station becomes a crewed facility surrounded by free flyers where microgravity manufacturing and scientific or commercial development projects are conducted without the constant presence of crew with their disruptive impacts on the working environment. In effect, the space station would become a habitat, a combination of hotel and dormitory for those supporting the space industry and scientific work being conducted in orbit. Bigelow had already begun development of habitats so creating such an arrangement would not require the same scope of work as building the ISS.

Such an approach expands the possible work that can be accomplished there. Tourists could be on the ISS-2 or hotel habitats nearby, providing support services in a central location. Pulling together resources and talent requires a broader appeal, which a ISS-2 can do, but someone ultimately has to lead. The US did so once (although honestly that was not the original intent) and can do so again.

| Both of these priorities are offered with the goal of actually making outer space truly a realm of human activity. Rather than remaining the sphere of individuals specially selected and trained, space truly becomes the next human frontier. |

Second, the current structure of the Artemis Program duplicates the earlier Apollo program in that the first missions are a launch, landing on the lunar surface, and returning to Earth. The lunar-orbiting space station, the Gateway, is being bypassed initially, raising the question of its purpose. What is proposed here is not a lunar-orbiting space station (that already exists in concept) but transportation between Earth orbit and the Moon. In 1969, the Space Task Group proposed a plan for the post-Apollo future space program. One component was a space tug so crewed flight between the Earth-orbiting space station and the lunar-orbiting space station, from there to the lunar surface. For budget and other reasons, President Nixon rejected this plan, ultimately approving only the space shuttle.

Such a space tug would not land at either end of its journey. Different configurations can carry cargo, passengers, or a combination. Such vehicles make cislunar space including the Lagrange points accessible by reducing flight costs—otherwise you have mount a specific mission from Earth to accomplish the task. No longer would a mission be a one-off; rather, the economic and human development possibilities would expand.

Both of these priorities are offered with the goal of actually making outer space truly a realm of human activity. Rather than remaining the sphere of individuals specially selected and trained, space truly becomes the next human frontier. That could be part of the legacy of the Biden Administration, building on the Trump legacy of the Artemis program; both look to the future.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.