Smallsat launch: big versus smallby Jeff Foust

|

| “Any early launches of a launch system carry a certain amount of risk,” Hart said. |

In a call with reporters ahead of the second launch attempt, Virgin Orbit CEO Dan Hart said that the company went through a thorough technical review to both identify the cause of the failure and take steps to correct it. The company brought in what he described as “some of the best industry experts,” including former chief engineers for the Atlas and Delta launch vehicles.

Virgin Orbit took steps to improve the first stage propulsion system and put it through extensive tests to confirm it could handle the launch environment, and took similar steps with the upper stage, which didn’t get a chance to operate in last May’s flight. “There were some minor mods that we made there as well,” Hart said.

Unlike the first flight, a pure launch demonstration with no payloads, Launch Demo 2 would carry satellites: ten cubesats from eight universities and one NASA center, arranged through the agency’s Cubesat Launch Initiative program. NASA awarded a contract to Virgin Galactic (before the LauncherOne program was spun out into a separate company) in 2015 as part of its Venture Class Launch Services program to support emerging small launch vehicles.

Despite the payload, Hart emphasized this was a test flight. “Any early launches of a launch system carry a certain amount of risk,” he said.

However, the flight went about as smoothly as the company could have expected. About an hour after the 747 took off from the Mojave Air and Space Port, it released LauncherOne off the Southern California coast. With the company electing not to provide a live public webcast (there was an internal one for customers and employees, as it turned out), Virgin Orbit provided updates via Twitter, with increasing levels of elation as the rocket ignited its engine and soared towards orbit:

“Still got a ways to go, but we just confirmed successful stage separation! This is a HUGE milestone, and the furthest our rocket has flown yet. C'mon LauncherOne!”

“Hearing that we've now crossed 50 miles for the first time and are still on track. Just... wow! WELCOME TO SPACE, LAUNCHERONE!”

“According to telemetry, LauncherOne has reached orbit! Everyone on the team who is not in mission control right now is going absolutely bonkers. Even the folks on comms are trying really hard not to sound too excited.”

After a 46-minute coast, the rocket fired the upper stage’s NewtonFour engine again briefly, then released the payloads, although it took the company more than an hour to confirm that those final steps in the flight went as planned.

“A new gateway to space has just sprung open,” Hart said in a statement after the launch, thanking the company for its “laser focus” on the test flight after the failure of the first launch and amid the ongoing pandemic. “That effort paid off today with a beautifully executed mission, and we couldn’t be happier.”

| “The hardware on this system performed flawlessly through the entire flight,” Kemp said. “This far exceeded our team’s expectations.” |

Virgin Orbit said it’s ready to enter commercial service with LauncherOne, but did not announce a customer or schedule for its next launch. The company has several rockets in various stages of productions at its Long Beach, California, factory, with the next vehicle “few weeks away from being ready,” Hart said before the launch.

The success of LauncherOne came a month after another small launch vehicle company came close to reaching orbit on its second launch. Astra launched its Rocket 3.2 vehicle from Pacific Spaceport Complex - Alaska on Kodiak Island December 15, three months after the launch of Rocket 3.1 failed seconds after liftoff. On that earlier flight, an oscillation induced in the rocket by its guidance system trigged an engine shutdown, causing the rocket to fall back to the ground and explode.

This time, the rocket’s first stage burned as planned, and the second stage followed. The only problem for the launch was that the upper stage shut down 12 to 15 seconds prematurely when it ran out of fuel, keeping it from reaching orbit. Rocket 3.2 reached an apogee of 390 kilometers before plunging back into the Pacific downrange from Kodiak.

Earlier last year, Astra projected needed three launch attempts to demonstrate it could put a payload into orbit, so narrowly missing orbit on its second launch was deemed a success by company executives. “The hardware on this system performed flawlessly through the entire flight,” Astra CEO Chris Kemp said in a call with reporters after the launch. “This far exceeded our team’s expectations.”

Kemp said the next vehicle—Rocket 3.3, logically enough—would be ready for launch in a few months. That vehicle may be the first to carry a payload, he said, given increased confidence that it will be able to achieve orbit.

Astra and Virgin Orbit’s accomplishments are signs that the commercial small launch vehicle industry, after years of development, is finally ready for prime time. Those companies, as well as industry leader Rocket Lab, are not alone. Firefly is planning a first launch of its Alpha rocket as soon as next month from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. ABL Space is readying its first rocket for a launch this spring, also from Vandenberg. Relativity Space, buoyed by a $500 million round of venture funding raised last fall, expects to launch its first Terran 1 rocket from Cape Canaveral late this year.

For those companies, and others, finally getting to flight can seem like a light at the end of a long tunnel for development. However, that light might turn out to be from an oncoming train, in the form of SpaceX.

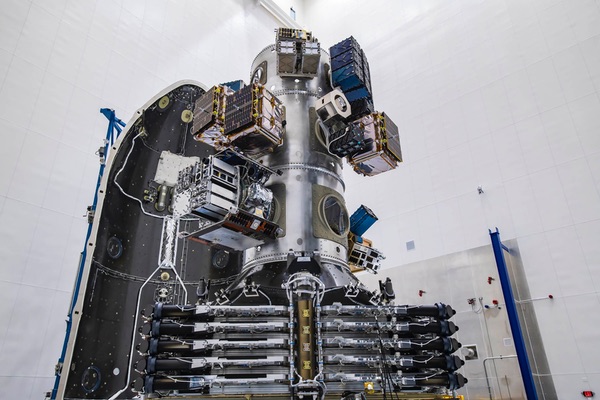

The payload stack for SpaceX’s Transporter-1 rideshare mission, which launched 143 satellites January 24. (credit: SpaceX) |

A week after Virgin Orbit’s successful LauncherOne flight, a Falcon 9 lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida. At first glance it was no different from the roughly two dozen launches the company performed last year alone. One minor difference is that the Falcon 9 flew south, making only its second launch to a polar orbit from Florida.

The bigger difference was what was inside the payload fairing. Rather than a single large communications satellite, or another set of 60 Starlink satellites, was a complex stack of smallsats and payload adapters. The Transporter-1 mission was the company’s first dedicated rideshare mission, and the 143 satellites on board set a record for the most deployed on a single launch.

Rideshare is nothing new for smallsats. The old record for number of satellites launched was set by an Indian PSLV launch a few years ago that carried 104 satellites. However, despite the size, that earlier launch was still something like conventional rideshare: a single large payload—a Cartosat imaging satellite—with other payloads taking advantage of the additional capacity. Nearly all the secondary payloads came from two companies: Planet, which launched 88 of its Dove imaging cubesats, and Spire, which launched eight of its weather and tracking cubesats.

| “The new rideshare program that SpaceX has put together has reduced the price on the order of four or five times on a per-kilogram basis,” Kargieman said. |

By contrast, there was no primary payload on Transporter-1: it was designed to be filled with cubesats and other smallsats. (SpaceX did something similar in 2018, launching 64 satellites, but that SSO-A mission was arranged by Spaceflight rather than SpaceX itself.) That resulted in a remarkable diversity of payloads, some that contracted directly with SpaceX and others that worked with payload aggregators, such as D-Orbit, Exolaunch, Nanoracks, and Spaceflight.

That resulted in some odd bedfellows. Three companies developing synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite systems launched spacecraft on Transporter-1: three for Iceye, two for Capella, and one for iQPS, a Japanese company. Astrocast, Kepler, and Swarm, three companies offering Internet of Things connectivity services, all had satellites on the launch. Planet launched 48 satellites, splitting them between its own contract with SpaceX and deals with two aggregators. SpaceX threw in 10 Starlink satellites after winning FCC approval earlier in the month to place those satellites into a polar orbit.

There were so many satellites on Transporter-1 that it was difficult to keep track of which companies and organizations had satellites on the vehicle, and with whom they arranged those launches. Some announced their plans in advance, while others waited until after the successful launch to announce at least some, but not always all, of their payloads. Journalists and analysts spent hours tracking down which satellites were launching.

As the name suggests, Transporter-1 is the first in a series of dedicated rideshare missions. SpaceX announced a formal rideshare program nearly 18 months ago, and last February updated its plans, including allowing customers to book spaces on flights through its website. That program also offers space on Starlink missions, and last year SpaceX flew satellites for BlackSky and Planet on three Starlink flights, taking off a few Starlink satellites to accommodate the rideshare payloads.

SpaceX is offering low prices for its rideshare opportunities: $1 million for up to 200 kilograms to Sun-synchronous orbit, a price far less than small launch vehicles, assuming they can place 200 kilograms into orbit. That price, and the promise of a regular series of flights, is attracting interest from aggregators and spacecraft operators.

An example is Satellogic, a company developing a constellation of high-resolution imaging satellites. The company has launched more than 20 satellites to date, primarily through rideshare opportunities. In November, it launched 10 satellites on a dedicated Long March 6 mission. (Satellogic, based in Buenos Aires, isn’t subject to export restrictions to China, unlike American companies.)

Last week, though, it announced a multi-launch services agreement with SpaceX, making SpaceX its preferred launch provider for the remainder of its constellation, slated to reach 60 satellites by the end of next year. That includes four launches on dedicated rideshare missions and options to fly satellites on Starlink missions.

“The new rideshare program that SpaceX has put together has reduced the price on the order of four or five times on a per-kilogram basis,” Satellogic CEO Emiliano Kargieman said in an interview. “That really made the rideshare program compete very well in the market and it caused us to start having conversations with SpaceX.”

That should be cause for concern for small launch vehicle companies. They have increasingly emphasized their flexibility, including the ability to tailor their missions to the desired orbit and schedule of their customers. One example of that was last week, when Rocket Lab launched an Electron rocket, carrying a communications smallsat built by German manufacturer OHB for an undisclosed customer. Rocket Lab and OHB both emphasized that the dedicated mission went from contract signing to launch in less than six months.

However, during their launch webcast, SpaceX noted one customer, which it did not identify, went from contract to launch in less than six months. Moreover, the development of in-space transportation services—space tugs, in essence—to move satellites dropped off on rideshare missions to desired orbits negates some of the advantages of small launchers.

Small launch companies appear to be increasingly turning to government customers, who are more willing to pay a premium for dedicated launch services, to close their business case. Hart hinted at that earlier this month, before the Launch Demo 2 mission. “The market has shifted a little bit, where the moves that the government has made open up new opportunities there, and we’re very focused on that,” he said.

| “If you limit microlaunchers to a purely commercial market, there is no business case,” argued Israël. |

Indeed, as this story was being prepared for publication, Virgin Orbit announced a new launch contract with the Dutch military. The six-unit BRIK-II cubesat will test communications technologies and “demonstrate how nanosatellites can provide a meaningful contribution to military operations,” according to the release. (Ironically, BRIK-II will fly as a rideshare itself on another LauncherOne mission later this year.)

Some in the industry are skeptical the small launch vehicle, or “microlauncher,” market can survive without government support. “If you limit microlaunchers to a purely commercial market, there is no business case,” argued Stéphane Israël, CEO of Arianespace, earlier this month. He cited as an example Rocket Lab, which has done business with various US government agencies. “It allows Electron to launch for the commercial market.”

His comments come amid a debate in Europe about what level of support, it any, governments should provide to European small launch vehicle developers. “If you want to have a business case for microlaunchers in Europe, you need to have a willingness from the European defense departments to have a quick and response access to space,” he said.

Arianespace is offering rideshare services on its Vega rocket, its smallest launch vehicle but one with a capacity significantly greater than emerging small launchers. “It will be the difference between a taxi and a bus,” he said, invoking the oft-used analogy for comparing dedicated small launch vehicles and rideshare services. “We offer a bus, which is cheaper.”

Some customers, many in the industry argue, prefer the flexibility the taxi offers and will pay a higher fare for it. But if the bus has a cheap fare and runs frequently enough to destinations desired by customers, as SpaceX may be offering, there might not be a lot of demand for that growing fleet of taxis.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.