“Space ethics” according to space ethicistsby James S.J. Schwartz and Tony Milligan

|

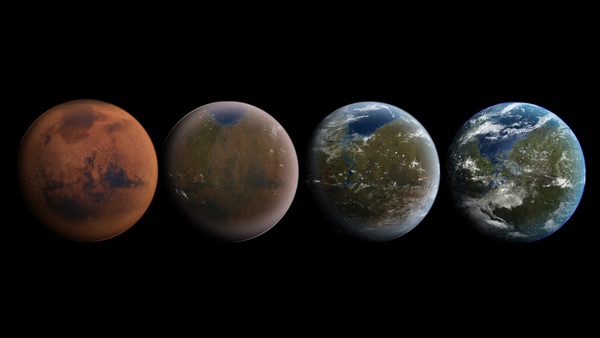

| Something resembling “space ethics” has been around since at least the 1980s, when serious research was conducted into the feasibility of terraforming Mars. |

In spite of their significant differences, neither op-ed presented a clear and unambiguous characterization of space ethics (aka the “ethics of space exploration,” and occasionally “astroethics”). That is understandable. The articles touched upon ethics but were not actually by ethicists—although, in fairness, people within our profession (i.e. ethicists) have also been known to be less than precise about our specializations. We may also have slipped in this direction too, from time to time. So, in response to Zubrin, Sercel, and Kwast, we would like to add some clarification, make it known that “space ethics” already exists, and that it does tend (as Sercel and Kwast anticipated) to support and aid the project of space exploration when conducted in defensible ways, and for good reasons.

This does not exclude critical evaluation of the sort that Zubrin took exception to in the EDIWG white paper, and particularly its claim that our existing understanding of “planetary protection” cannot do all of the work that we would like it to do. This is not, incidentally, a new idea, but a recurring theme in discussions of the concept for over a decade. Something newer is called for, be it an extended version of the concept (the argument of the EDIWG white paper), or an additional concept such as “planetary environmental protection” (an idea which the authors are sympathetic to.) Both are good and effective pathways to keeping space policy aligned with our evolving societal norms, rather than tied to those of the 1970s. Such realignment is not a threat, or an assault, but a practical necessity if space exploration is to sustain a sense of legitimacy before the broader public who, through their taxes, ultimately provide the funding for NASA.

Either way, something resembling “space ethics” has been around since at least the 1980s, when serious research was conducted into the feasibility of terraforming Mars. To the credit of many of the scientists engaged in this research, attempts were made to determine whether this was the kind of thing that we ought to do, and when it might be reasonable to try. A wildcat attempt to melt portions of the Mars icecaps to boost the atmosphere could, after all, go badly wrong and compromise future opportunities when the appropriate technologies are in place. These early discussions mainly involved scientists and environmental ethicists, and resulted in the seminal anthology Beyond Spaceship Earth: Environmental Ethics and the Solar System (1986), edited by Eugene Hargrove, founder of the venerable journal Environmental Ethics.

There was some gathering of the pace of research in the 1990s, with David Duemler’s schematic application of philosophical ethics in Bringing Life to the Stars (1993), continuing with the more precise and detailed study of ethical issues surrounding the Space Shuttle in Rosa Pinkus et al.’s Engineering Ethics: Balancing Cost, Schedule, and Risk (1997), which applied ethics in a more pragmatic, recognizable workaday way. Momentum was added by the discussion surrounding the premature (and ultimately mistaken) 1996 announcements about the Allan Hills 84001 Martian meteorite fragment, which some scientists (briefly) thought might contain evidence of microbial Martian life.

Many scientists from NASA and the broader space community quickly realized the importance Carl Sagan’s question of whether or not such rudimentary Martian life could have moral standing. (Not equal standing with humans, but moral standing of a sort that would warrant protection nevertheless.) It was also realized that interdisciplinary work with ethicists would be important for thinking clearly about such matters. After all, it is difficult to say just what it would mean in practice to value rudimentary alien life, especially when this sounds so far removed from our existing senses of our responsibilities. On the one hand, it would probably involve saying that we have certain duties to protect and conserve rudimentary alien life (on Mars or anywhere else we might discover it). But would these duties be excessively constraining? Would they get in the way of science, or commerce, or both?

| We hope it is clear that space ethics is an offshoot of spaceflight itself, as opposed to something with an outsider backstory. |

These discussions have continued, but over the next decade and a half were supplemented with the first attempts to flesh out views of ethics that make room for the novelty of encountering microbial alien life, without simply subsuming it into existing ethical discourse (and especially not rights discourse, which is far more suited to humans and animals than to anything microbial.) This provisional phase of the discipline culminated in the Pompidou report for the European Space Agency and UNESCO on The Ethics of Outer Space (2000), which contained an impressive mixture of speculations, forward looking pragmatism, and commitment to the practical value of ethics.

In the first decade of the new millennium, the majority of space ethics was not, however, being done by professional ethicists. It was carried out by well-informed scientists and other members of the spaceflight community who shared a sustained interest in ethical questions, including Linda Billings, Charles Cockell, Robert Haynes, Mark Lupisella, Christopher McKay, Margaret Race, and John Rummel, all well-known researchers with appropriate institutional connections. These individuals could be considered key “early adopters” of using philosophical techniques and ethical insights to explore the possible discovery alien life, the environmental side to the protection of the Martian landscape, and the human and cultural significance of space exploration.

In the 2010s, as the space ambitions of Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos were gaining momentum and bringing increased attention to space activities, the early adopters were joined by scholars from related disciplines such as anthropology and sociology, and a cluster of more specialized space ethicists (that is, people like the authors.) This led to the formation of what could be called a “societal dimensions of space” resource community, or, in a term that has become popular in new technologically-related fields, an “ELSI” community, looking at ethical, legal, and societal implications. “Space ethics,” in turn, refers to the characteristically ethical research conducted by members of this community, though it is worth pointing out that the vast majority of scholars who self-identify as “space ethicists” are professional philosophers.

The result has been a flowering of research and publications specifically on space ethics, with key publications including an expanded translation of Jacques Arnould’s Icarus’ Second Chance: The Basis and Perspectives of Space Ethics (2010) from the original French (though Arnould’s pioneering work dates back to the Pompidou report), Tony Milligan’s Nobody Owns the Moon: The Ethics of Space Exploitation (2015), James Schwartz’s and Milligan’s edited volume The Ethics of Space Exploration (2016), Charles Cockell’s three-volume edited series on extraterrestrial liberty, Konrad Szocik’s edited volumes The Human Factor in a Mission to Mars (2019) and Human Enhancements for Space Missions (2020), Schwartz’s The Value of Science in Space Exploration (2020), and Kelly Smith’s and Carlos Mariscal’s edited collection Social and Conceptual Issues in Astrobiology (2020).

There are various other volumes that might be added to the above list, as well as hundreds of shorter publications on matters of space ethics in peer-reviewed philosophy, space policy, and space science journals. Most of our own work appears in places of this sort. Meanwhile, on the curricular side, a few innovative universities are already teaching space ethics, and occasionally dedicated courses on space ethics.

With this brief historical sketch, we hope it is clear that space ethics is an offshoot of spaceflight itself, as opposed to something with an outsider backstory. Given this, worries about “wokeist” assaults on space seem misplaced, at least unless the complaint all along has been that contemporary ethics is irredeemably wokeist (which is simply not true on any reasonable understanding of “wokeist”.) Space ethicists, including the minority who have openly progressive research agendas, neither have nor claim to have anything approaching the sociocultural significance or influence of advocacy groups like Black Lives Matter or rallying-calls such as “Defund The Police.”

What’s more, the influence of space ethics lags far, far behind the influence of dedicated space advocacy groups like the Mars Society and the National Space Society. That some might perceive “space ethics” as a threat probably says more about its detractors than it says about space ethics. “Progressive space activism,” to coin a phrase, isn’t our day job, even if our day job does require some of us to seriously entertain progressive ideas and proposals as part of a larger, ideologically inclusive conversation about space exploration.

| If you are expecting space ethics to tell you that space exploration is the greatest thing ever, and that we should plunge ahead at all deliberate speed, then you may be in for a disappointment. You are also in for a disappointment if you are expecting space ethics to validate calls to renounce space exploration and to accept our terrestrial horizons. |

So what, then, do space ethicists actually do? At the highest level of generality, we are simply here to ask the ethical questions that, sooner or later, will need to be asked. And it is a feature of the practice of ethics, and not a bug, that it produces productive disagreements about the answers. But more specifically, there are five broad roles that characterize the vast majority of space ethics research. There are no doubt others that will emerge in the future, as space ethics is an evolving discipline. But the following list captures its “settled” roles and responsibilities.

1. Space ethics identifies principles for arriving at rational compromises between different stakeholders in space. Space exploration is not a monolith; it is not just “one thing,” which makes “supporting” and “opposing” spaceflight (as well as “assaulting” spaceflight) ambiguous notions, compatible with a great many specific positions. Space exploration includes a diverse range of activities representing a diverse range of goals and objectives: Earth observation for scientific, economic, political, and defense purposes; satellite telecommunications; space tourism; scientific research and exploration (crewed and robotic); and, possibly in the future, manufacturing, geoengineering, space mining and space settlement.

These activities compete over territory and resources, and they are coming increasingly into conflict with one another, especially with the scaling up of commercial spaceflight activities over the last decade. In Earth orbit, we are already at the point where push comes to shove: there are only so many positions in which satellites can be placed, and with the increasing debris threat, the sustainability of satellite operations is in doubt.

The Moon could soon face a similar crowding problem, as many of the landers planned for the next decade target the same few locations. The long debate about whether Mars should be protected for the sake of scientific research (or for the sake of any life that might exist there), conflicting with the goals of aspiring space miners and settlers, is heating up as plans such as those of Musk move closer to becoming realities.

How do we balance these conflicting interests? What values should be recognized? Whose interests matter most? Which spaceflight objectives are likely to serve the greater human good and which might further inequality and carry various kinds of societal risk? In a very direct sense, space ethics exists to help us figure out matters of this sort and what is worth doing in space. Which leads to our next point: There is little justification for claiming that we already have the answers.

2. Space ethics is not inherently enabling or disabling of any specific spaceflight activities; it is a tool for improving how we reason and make decisions about space. That space exploration is important, worthwhile, or necessary is not in any way a basic assumption of space ethics. Space ethics does not exist merely to confirm enthusiasm for space. (Don’t get us wrong; most space ethicists think space is awesome, and we’re far bigger space nerds than we get credit for!) These are conclusions that might be reached by space ethicists, but whether they are ever reached depends on whether there are viable assumptions that, together with various other accepted claims, point toward the value, importance, or necessity of space exploration.

Some space exploration activities may be more important, necessary, or valuable than others. Space ethics might validate the importance of Earth observing satellites but deny the value of space tourism. Space ethics might validate space tourism but deny the importance of scientific exploration. Ethics, being part of philosophy, which is itself devoted to examining the contours of reasoning and the boundaries of our concepts, is especially well suited to addressing the quality of arguments presented for and against spaceflight activities of different kinds, without lapsing into slogans or convenient fallacies.

Interestingly, this is distinct from the take that Sercel and Kwast have on space ethics. They anticipate that space ethics would automatically affirm the need to “update international space law to recognize property ownership and salvage rights” and that it would answer the “call to move forward as fast as feasible to ethically explore space and do the research that will enable settlement of the high frontier.” This is a legitimate point of view, and various things can be said in its favor, but there are space ethicists who argue for this and some who argue against it. Moreover, the underlying justification for clarifying property rights in space (that this will enable space mining and space settlement) is itself a contentious matter. Similarly, there are compelling ethical arguments both for and against space settlement, and for attempting it sooner versus taking a cautious approach. To think of space ethics as constructive and productive is not the same as holding that it exists for the purpose of validating what we have already decided to do.

In a sense, this goes to the heart of the matter, and why space ethics matters: it helps us to identify and reconsider assumptions that space advocates as well as space skeptics often fail to realize that they are making. In some cases, these assumptions turn out to be entirely reasonable. In others, they turn out to be highly questionable. If you are expecting space ethics to tell you that space exploration is the greatest thing ever, and that we should plunge ahead at all deliberate speed, then you may be in for a disappointment. You are also in for a disappointment if you are expecting space ethics to validate calls to renounce space exploration and to accept our terrestrial horizons.

| If space truly promises a boon to all of humanity, then it should be possible to demonstrate this without relying solely on some fairly narrow perspective from either end of the political spectrum, or perspectives which show an unhealthy obsession with the state versus market debates of the 20th century. |

Space ethics is not on “my side” or on “your side.” It is not on the side of space development, or on the side of planetary protection. It is a discipline in which people may act partisan, and imagine that they are at the sharp end of history, but it is not itself a partisan discipline. Sometimes, the things we want to be true will turn out to be unjustified. And whenever this happens, the fault, if there is one, will be in our expectations and not in the stars.

3. Not only does space ethics help us figure out what is worth doing in space, it also helps us figure out the best way to do those things. Suppose, for example, we have agreed that there is an ethical obligation to exploit the water ice deposits in the permanently shadowed regions on the Moon. At that point we would face an entirely new set of ethical questions: How should this exploitation be conducted? What is a tolerable extraction efficiency level? Who should be permitted to conduct the exploitation? And so on.

However, just because we agree on an outcome doesn’t mean we have figured out how to actually secure or bring about that outcome. If the legitimate goal of space resource exploitation is to improve human well-being, then not every mechanism or mining regime will be equally likely to accomplish this. If there are multiple legitimate goals, then how do we reach a consensus when they clash? Can either the state or an unfettered free market be trusted to produce reasonably just outcomes? Is the whole “market-versus-state” discourse the kind of thing that we want to be taking into space in the first place?

Space ethics reminds us that dogmatic adherence to preferred economic and political systems will not help us resolve these kinds of disputes, one way or the other. Enthusiasm is no substitute for analysis, especially when lives and billions of dollars of public money are at stake.

4. Space ethics helps us gain perspective. Part of carefully examining our assumptions about space is ensuring that we look at space-related issues from as many perspectives and conceptual frames as possible. It is rare that American space advocates ever have to grapple with non-American, non-Caucasian, non-libertarian conceptual frameworks and value systems. But examining a broader spectrum of human cultures and perspectives is absolutely vital for increasing our confidence that we are doing the right things, for the right reasons, in the best ways.

If we fail to do this, we invite the risk that the projects we begin will not be continued by others. In the case of multi-generational projects such as human expansion into space, this is particularly important. What we do should make sense to those who come after, and one of our best guides to whether it will do so or not is the way in which it addresses concerns which can be seen from multiple perspectives and across multiple cultures. This is not wokeness or assault, but a concern for the stability of projects, given the strong likelihood of cultural and political change over time.

Here, it is worth noting that space advocacy in the past and, to a receding but still concerning degree in the present, tends to marginalize the perspectives of women, of persons of color, of indigenous persons, of persons from African, Asian, European, or Middle Eastern cultures, of disabled persons, as well as members of the LGBTQIA community. Taken together, these are not a woke minority but the majority of humans on our planet. If space truly promises a boon to all of humanity, then it should be possible to demonstrate this without relying solely on some fairly narrow perspective from either end of the political spectrum, or perspectives which show an unhealthy obsession with the state versus market debates of the 20th century.

While space ethics teaches us to seek a wider perspective, it is not the only fount of perspective. We should also seek insights from anthropologists, historians, political scientists, sociologists, astronomers, engineers, poets, artists, and dancers. Few fields of inquiry or modes of creative expression fail to add value to our understanding of space exploration as a human endeavor.

5. Crucially, space ethics is an ongoing activity. Ethics, for space or otherwise, is not something that you do only “before” you pursue a project. It is something you have to do while you are completing the project and continue to do long after its completion. In this respect space ethics is indeed analogous to bioethics, as Sercel and Kwast reasonably and usefully point out.

This analogy has obvious limits: spaceflight (the focus of space ethics) and medical care (a major focus of bioethics) are very different things. But they are similar in that each pursues large-scale, expensive, multi-year projects that have the potential to impact the well-being of the wider public in beneficial and injurious ways. As a result, there are revealing similarities between the ethical questions we ought to raise when evaluating new projects and proposals, whether they are spaceflight proposals or medical care proposals. In this narrow sense, planning a new space mission is a lot like planning new construction on a hospital.

| We will never be free from the need to ask whether we are doing the right thing, for the right reasons, and in the best ways. |

We need to ask ethical questions during the planning phase in which we are figuring out what to do: Where is the best location for the hospital? Where are the patients in most need? Which services should the hospital provide? Should it be public or for-profit (and if healthcare involves both, which should this one be)? How do we keep it open once it has been built? To what degree is it permissible for “all things considered” cost-reduction and economic sustainability to override community health needs and priorities? Comparably, for a space activity or mission we would need to ask: What is the target destination? What objectives should be prioritized? Which instruments or capabilities should be included? To what degree is it permissible to trade off or sacrifice goals because of cost limitations? What are the risks involved, and who are the risk takers and potential beneficiaries?

The need for ethical evaluation continues through the design and construction phase, where we are determining how to do things: How well should the designers and construction workers building a hospital be paid, given finite funds, and a possible trade-off between fairness in construction and in long-term quality of care? What if something unexpected happens during construction? To what degree can cost overruns justify design changes which might have later and undesirable consequences? And ethical questions persist long after the hospital opens: Which patients should receive which treatments? Does it matter whether a patient has insurance? Is euthanasia ever permissible and what should triage look like? In each case, there are similar questions we might pose during the construction of spaceflight kit and hardware, during the preparation stage for flight, and throughout the implementation of the mission or activity.

Ethics does not stop once the countdown reaches T-0:00. It is not the kind of thing that we will ever be done with, at least if it is the kind of ethics that reaches deep within our human lives and the things we do. We will never be free from the need to ask whether we are doing the right thing, for the right reasons, and in the best ways.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments submitted to deal with a surge in spam.