The politics of settling spaceby Gregory Anderson

|

| If all goes well, humanity is on the verge of another historically significant migration: the first wave of the human settlement of space. |

These days, space advocates like to assert that exploration is part of human nature, citing history, including the move out of Africa. Exploration is likely a complex phenomenon—most humans, after all, never did it in the grand, physical sense—and it’s not clear those first humans to leave Africa were actually exploring. They were likely searching for food, for safety, for an easier life. Evidence seems to suggest they initially followed coastlines, where food might have been easier to gather. At some point, they seem to have mastered sailing enough to reach Australia. At some point, too, groups obviously turned inland, to settle everywhere in Eurasia. Exactly where deliberate exploration came into the picture may be difficult to determine.

Since then, there have been many attempts at exploration, many surges of migration, and many waves of settlement, all of which have happened for various reasons. Often, groups have moved voluntarily, but not infrequently groups have been forced to settle elsewhere by more powerful groups or by governments. Migrations have been undertaken for various reasons, including religious, economic, and cultural. If all goes well, humanity is on the verge of another historically significant migration: the first wave of the human settlement of space. That migration will follow exploration by telescopes, probes, rovers, and humans. This settlement era will be no less complex.

The politics of settling space will be guided, in the first instance, by biology. We know from space station studies that humans would not do well living their lives in microgravity. Therefore, space settlements will have to have either natural gravity—that is, be built on a substantial world—or make use of artificial gravity, as in the famous O’Neill torus colonies. The next question is, how much gravity is enough? Do humans require Earth normal gravity, or will Martian gravity do? Or lunar gravity? Determining the answers to that suite of questions will shape settlement policies. If lunar gravity is sufficient to allow everyday human functioning, we can be off to the races soon. If lunar gravity is not, but Martian gravity is, that could mean Mars will get the full-blown settlements with moms and dads and kids, while the Moon only gets bases. If neither world has enough gravity, we might be driven to the O’Neills, where we can control gravity. That’s an attractive option, but it would delay settlements.

| Settlement policies will reflect the physical realities of space, but they will also be dependent on the political and economic realities of Earth. |

Gravity isn’t just about healthy adults, either. Self-sustaining communities demand procreation. The erotic fantasies of generations of science fiction authors aside, we don’t know yet whether sexual couplings in microgravity or low gravity can lead to normal fertilization of the egg, nor do we know yet whether a fetus would develop properly. For that matter, we don’t know children would develop properly in low-gravity states. We have much to learn.

Settlement policies will reflect the physical realities of space, but they will also be dependent on the political and economic realities of Earth. In turn, the nature of space settlements and their relationship with Earth will depend on when they are built, who builds them, and why they are built. If they are not built for 500 years, or even 100 years, we can’t say too much about motivations; we have no way to determine what the specifics driving those decisions will be. There is a tendency in this area to speak of “Earth” as the controllers of space policy. That might be the case sometime in the future, but in the near term, there will likely be a welter of sponsors and policies.

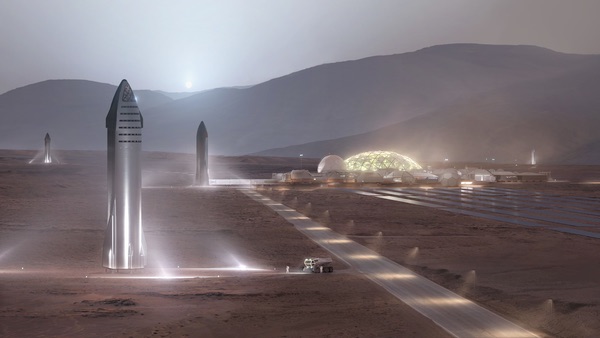

There are nations that might establish settlements beyond Earth sometime within the next few decades: the United States, China, Europe, and perhaps Russia or Japan. The United Arab Emirates plans to have a colony on Mars within a century, and has a probe orbiting the Red Planet even now. Various combinations of nations could. There are also non-national possibilities. Elon Musk plans to plant a settlement on Mars. Mars One has similar ambitions, although that project seems to have failed. Bigelow Aerospace had been building huge inflatable modules capable of establishing orbiting space stations and bases on the Moon or Mars. Such bases can be expanded to full-blown settlements. Bigelow seems to have shut down, but other companies are on the rise with big plans.

Settlements established in each of those circumstances would be different in character than others. Each would pursue its own strategy. Each would have its own relationship with its sponsor. Some may be colonies of nations in the traditional sense of that term, a uniquely valuable asset. Others may be more loosely connected to any of several sponsors. Still others might be essentially free to pursue their futures as their people see fit.

Quite apart from what might be scientifically or technologically possible, space advocates have been hard pressed to articulate why we should settle space now, given all the problems of Earth now. Answering that fully is beyond the scope of this essay, but at least one possible answer bears on the political structure of a settlement system and that is numbers. Most humans alive today live in poverty. Most lack adequate healthcare, let alone the level of care available to people in the West. Clean water is elusive for billions of people. Throw in possible economic collapse, climate change, and a human population that is still booming, and a grim future could await humanity. Liberal democratic values could be abandoned in favor of authoritarian rule as people try to trade freedom for security. One key to building a positive future beyond such chaos would be building a larger, expanding human economy that would allow dealing with problems from a position of economic strength, not weakness. One way to expand the economy is to physically expand into space to create new industries and new wealth.

There are other ways to build a bigger economy, of course, and much to do to lift the poor regions of Earth into the 21st century. Progress is already being made in sub-Saharan Africa, but more needs to be done more quickly. Many national populations in the Middle East are extremely young and restive. That has the potential for great change. Education will be key to allowing people to compete successfully in a society increasingly based on science and technology. Modern infrastructure must be built where nothing exists today. Agricultural output must be increased. Projections by the UN are that there will be 11 billion humans alive in 2100. They will all need a good diet, access to the best healthcare, a quality education, and the opportunity to build for themselves the lives each individual chooses to lead. Getting there will be an immense challenge across the board, but expanding into space, as one element in an overall strategy, can be extremely useful. Tapping into huge new resource bases, using an essentially inexhaustible energy supply based in solar power, and experimenting with various gravity states will expand our scientific knowledge and our technological capability, and begin to lay the groundwork for an enduring civilization.

Skeptics of moving into space often argue we need to solve the problems of Earth before we go anywhere else. Civilizations might reach a time of decision in their development, however. Having reached a certain size and technological sophistication, they can choose to reach into space in an attempt to maintain their vitality, or they can choose to remain on one planet and accept the possibility of an eventual decline and collapse.

| Some have argued such settlements will tend towards authoritarian government because of the danger involved, but in fact they will be the perfect environment for pure democracy: small groups of highly educated, highly motivated, self-starting individuals committed to the community who will have all relevant information at their fingertips. |

Before moving into space in a massive, sustained way, the legal situation needs to be clarified. The main treaty defining space law today is still the 1967 Outer Space Treaty negotiated largely by the United States and the former Soviet Union. Among other things, the treaty prohibits any nation from claiming a celestial body or any part thereof, which is why Apollo astronauts didn’t claim the Moon as US territory. Would a nation establish a colony on the Moon or Mars if It could not claim the surrounding area as its sovereign territory? What right does an Earth government have to another world, anyway? What about corporations: can they bring profits made in space back to Earth? We need to develop these aspects of space law. Nations such as the United States and Luxembourg are trying to establish space law by national statute, but a broad new treaty to govern the first phase of space settlement is preferable.

Once law is brought to the frontier, the real push out would presumably begin. Some nations may establish settlements tied directly to them, as colonies, to give themselves the economic advantages of microgravity manufacturing. Several nations might band together to build settlements on the Moon, with sovereignty shared, to establish a lunar economy based around manufacturing, tourism, and other industries. Corporations might build company towns. Each type of settlement will have a different relationship with its sponsor, and, therefore, with Earth. Some have argued such settlements will tend towards authoritarian government because of the danger involved, but in fact they will be the perfect environment for pure democracy: small groups of highly educated, highly motivated, self-starting individuals committed to the community who will have all relevant information at their fingertips. That’s the founding generation, of course. How each settlement grows and evolves politically and culturally over the years is anybody’s guess.

One thing we do know—the settlers of space will not be cut off from the rest of humanity. They will be in constant touch with Earth. They will have access to whatever the Internet has become by then, so they’ll be able to keep up with family and friends and news and movies. Since the solar system is only light-hours across from Pluto in, no matter how far out human settlements eventually reach, there will likely be a general cultural coherence centered on Earth. Each successful settlement can be expected to develop its own culture, as well, but much as English has become a lingua franca worldwide because of the dominance of the British Empire, democratic values and institutions have spread through centuries of European influence, and international popular culture has strong American elements, Earth will likely by a unifying factor for a long time.

Political coherence is another matter. Exactly how a political entity on Earth could project its authority into space to enforce its rule over a self-sufficient settlement is unclear. The political system that could evolve might have a few powers on Earth vying against each other, and each trying to control ever shifting alliances of small yet economically powerful city-states in space. It could get extremely complicated.

The politics of settling space will likely be too daunting for political leaders to tackle on their own. The opportunity to take the next step in establishing an enduring civilization could well come amidst chaos. If that next step is to be taken, the vision and courage of an engaged populace, expressed democratically, may be required.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.