Why venture? A memo for the Biden Administrationby Derek Webber

|

| It already seems clear that governmental funding will be necessary for at least the next decade; it is not yet clear when it might be possible for commercial businesses on the Moon to be self-sustaining. |

Under this category, we can certainly record the successes of weather forecasting and Earth observation technologies. Some have pointed out that we needed to leave the Earth in order to be able to look back and truly appreciate it. This task, of course, continues, and ozone-hole monitoring, climate change indicators, and human threats to the ecosystem continue to be recorded while solutions are proposed and debated and, hopefully, implemented. Most of this work began as governmental endeavor, but nowadays this has been augmented by commercial operators.

Category 2: Improving life on Earth

Under this category, we can consider initial governmental activities, which, however, quickly became the province of commercial operators. In fact, these were the first round of successful space businesses. They continue to generate wealth, funding via taxation, and employment opportunities. We include here building the spacecraft and launch vehicles supporting the satellite telecommunications and broadcast businesses, all those activities that rely on GPS or other satellite navigation services, and the nascent space tourism sector. In many ways, these businesses have been, and are, enablers of future space developments. These individual market sectors and associated spinoffs are where we have learned to develop spacefaring skills, to improve the reliability and lower the costs of space travel. This is ongoing and good business.

Category 3: Sustaining life on Earth

And now we are at the threshold of the next great step for continuing our space endeavors. This is where there is now a need for a clear visionary assessment of budgets and timeframes. This is where it is necessary to weigh the national and international frameworks for progress. The relevant timescales here are related to the assessed reserves on Earth of materials considered to be essential to humankind’s continued progress. Work is beginning to assess the likely future need for such resources as rare earth minerals versus the likely terrestrial reserves. But it is probable that we are talking in decades, which gives us a clue to budgeting needs. And initial experiments are planned to assess the availability of reserves of such materials on the Moon, Mars, and asteroids.

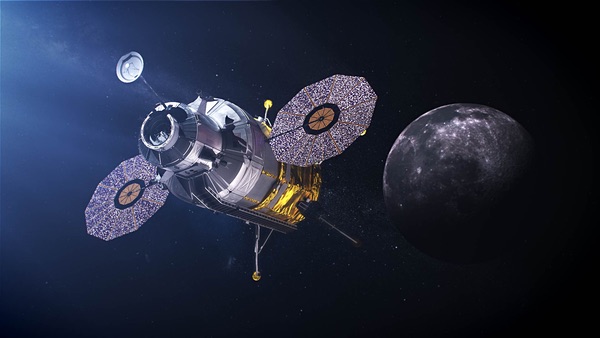

Already, NASA is planning the Artemis and supporting missions to the Moon to help derive this knowledge. The Artemis Accords have even been introduced as a way of engaging in peaceful, sustainable international operations on the Moon. The Russians and Chinese are also developing their own preferred approach. How should the national space budgets handle the efforts and timescales involved in this work? Is there any urgency? That may depend on external political factors, but with regards to the fundamentals we know that we need the time to study the availability of resources in off-Earth locations, and to learn how to process and extract them for use on Earth. A current endeavor by a Working Group of the Moon Village Association is trying to give guidance on these timescales, and the extent to which commercial entities will be able and willing to undertake the activities, at least in the case of the Moon.

| There are short-term and long-term reasons why we do space exploration, some of them even being existential, but all of them involving protecting, improving, and sustaining life on Earth. |

It already seems clear that governmental funding will be necessary for at least the next decade; it is not yet clear when it might be possible for commercial businesses on the Moon to be self-sustaining. Meanwhile, governments should budget to pursue experimentation and development activities, continue to seek improvements and economies in providing the sustaining infrastructure elements, and plan to develop the knowledge gained on the Moon for application elsewhere in the solar system, such as on Mars or asteroids.

Category 4: Ensuring survival

Finally, this category has been on the list of space travel rationales from the very beginning, with such visionaries as Tsiolkovsky even making the point in 1903. There is an inevitability about the need, but in most scenarios of Earth catastrophe the time of such an eventuality is so very far into the future—at least centuries, and possibly millions of years—that it is not possible in normal political discourse to include the funding to contemplate the requirements for activities to protect life itself. Nevertheless, this does represent the ultimate rationale for space exploration, and was at least alluded to by several of the early astronauts who risked their lives at the beginning of the space era. And, however far off these eventualities might be, we do know that they would make it impossible for life to continue on Earth, be they natural phenomena or caused by people. At least, some work has begun on how to approach the asteroid threat, and some budget is being allocated, although current indications are that there is no expected existential threat for at least another 100 years.

So, there we have it. I think we can agree, in a nonpartisan way (but I may be wrong!) that there are short-term and long-term reasons why we do space exploration, some of them even being existential, but all of them involving protecting, improving, and sustaining life on Earth. To the Biden Administration, I hope this is useful and can help identify appropriate expenditures and incentives for budgeting purposes. In particular, I hope it provides a framework for considering what the future holds in terms of lunar activities, which represent the next arena for our collective space development endeavor. Remember, we venture because we must!

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.