Review: The High Frontierby Jeff Foust

|

| Seeing that ’70s-era footage, and listening to the interviews, and one can understand why O’Neill’s vision captured the imagination of so many at the time. |

Outside that community, O’Neill is largely forgotten, even among many who work in the space industry in some way today. But at the peak of interest in space colonies in the 1970s, O’Neill was, at least briefly, in the cultural mainstream, appearing on “The Tonight Show” with Johnny Carson and profiled on “60 Minutes.” The prospect of giant cities in space, built of out lunar materials that could also support development of space solar power facilities, seemed at least in the realm of the possible at the time.

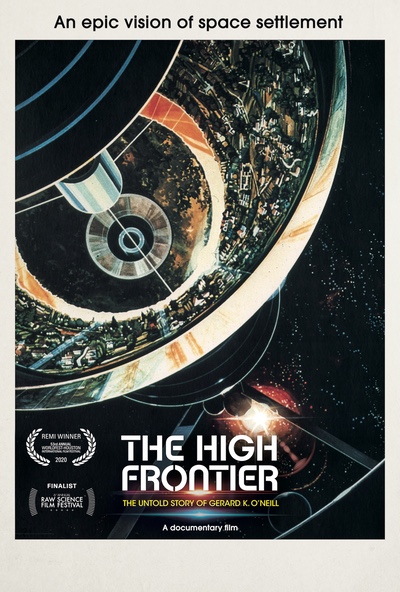

The new documentary The High Frontier: The Untold Story of Gerard K. O’Neill attempts to rekindle that interest while reexamining the life of O’Neill. The 90-minute film had its premiere Saturday night on the Space Channel online, and is now available to rent or buy on various services, including iTunes and Google Play.

The movie extensively uses archival footage, including those “The Tonight Show” and “60 Minutes” appearances, as well as another show where O’Neill appeared alongside Isaac Asimov. That footage is combined with interviews with his family, colleagues, and others who knew or were inspired by him. It’s a who’s-who of the space advocacy community, with people such as Rick Tumlinson, Peter Diamandis, and Lori Garver, as well as pioneers in the commercial space industry like Charles Chafer and Jeffrey Manber. (Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk also appear in the film, but in footage from speeches they gave rather than interviews with the filmmakers.)

Seeing that ’70s-era footage, and listening to the interviews, and one can understand why O’Neill’s vision captured the imagination of so many at the time. It offered a positive vision of the future during an era of environmental and energy crises, and a new direction for spaceflight as the original Space Race wound down. With the Space Shuttle soon to drastically lower the cost of space access, as it promised, it seemed only a matter of time before the first space colonies were built, even if the rallying cry of “L-5 in ’95” was optimistic.

So, what happened? The simple answer, of course, is that the shuttle failed to live up its expectations in terms of cost and frequency, but this is glossed over in the film. Whether those space settlements would have been technically and economically feasible if the shuttle had hit its cost and flight-rate targets isn’t addressed.

| “We were all Gerry’s kids. We’re all, in one way or another, caught up in this idea,” said Muncy. |

“The political climate wasn’t there and he wasn’t economically wildly successful,” O’Neill’s son, Edward, says in the documentary. O’Neill tried to be successfully economically, with a company called Geostar that planned to offer navigation services in the era before GPS was readily available. Geostar failed, though, which the film attributes to O’Neill’s declining health—he was diagnosed with leukemia in the mid ’80s, and would pass away in 1992—as well as infighting within the company. The movie doesn’t dwell on Geostar though, beyond Diamandis predicting that if Geostar had been successful, “we’d be on the Moon right now implementing Gerry’s visions.”

The film, though, makes clear the impact O’Neill had in his too-short life by offering a different vision for space, one that may have been far too difficult to achieve then (or now) but which motivated a generation of people who carried the torch for decades to come. “We were all Gerry’s kids. We’re all, in one way or another, caught up in this idea,” said Jim Muncy.

That message resonates to this day: Bezos, for example, cited O’Neill’s work as a primary motivation for him to pursue Blue Origin and its vision of millions of people living and working in space, to the point of, a couple years ago, offering updates of the classic ’70s imagery of space settlements. “The importance, in hindsight, of the ’80s was not the Space Shuttle program,” Manber said. “It was that we were allowed to dream in the ’80s, which led to the advances that we got in the ’90s and the new century.” The High Frontier reminds us why so many dreamed then, and now.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.