Review: Test Godsby Jeff Foust

|

| Scaled built prototypes, and took a minimalist approach to design: when one engineer proposed a backlit push button for one control on SpaceShipTwo, Scaled rejected it in favor of a toggle switch labeled with tape and a Sharpie. |

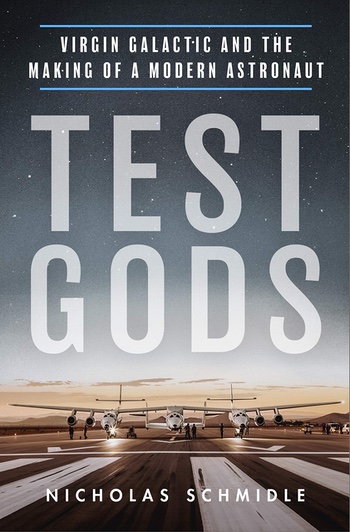

Virgin Galactic’s delays and setbacks have been well-chronicled here and elsewhere, but not to the same level of detail as in Nicholas Schmidle’s new book, Test Gods. Schmidle was embedded for several years in Virgin Galactic, starting not long after the October 2014 accident that destroyed the first SpaceShipTwo and killed its co-pilot, Mike Alsbury. He was such a frequent visitor to the company’s Mojave facilities, sitting in on meetings and interviewing people, that one new hire thought he was a fellow employee.

Schmidle tells the story of Virgin Galactic largely through one of its pilots, Mark Stucky, with whom he spent much of his time while at the company. Stucky was interested in becoming an astronaut since he was a kid in the early years of the Space Age, although his father discouraged him (as he had been raised a Mennonite and opposed serving in the military, at the time the only route to become an astronaut.) Stucky, though, joined the Marines after college as a pilot and later applied to NASA several times, becoming a finalist but never selected as an astronaut. He eventually went to work for Scaled, where SpaceShipTwo offered him one more chance to go into space.

That opportunity to fly would take far longer than what anyone expected. Much of that was linked to SpaceShipTwo’s hybrid propulsion system, including the 2007 accident in ground testing that killed three Scaled employees, and the difficulty SpaceDev had in developing the engine (Schmidle refers to the company as SpaceDev throughout the book even long after it was acquired by Sierra Nevada Corporation.) There was also a September 2011 glide flight where SpaceShipTwo started spinning out of control; Stucky, the pilot on that flight, saved the vehicle, and the lives of the three people on board, by activating the feathering mechanism.

The premature deployment of that feather by Alsbury on the October 2014 flight, though, killed Alsbury and seriously injured pilot Pete Siebold. It also highlighted the differences between Scaled and Virgin. Scaled built prototypes, and took a minimalist approach to design: when one engineer proposed a backlit push button for one control on SpaceShipTwo, Scaled rejected it in favor of a toggle switch labeled with tape and a Sharpie. That included a lack of inhibitors on controls, like the one activating the feather mechanism. That would change when Virgin took over the program after the accident; Stucky, a Scaled employee, joined Virgin shortly after the accident.

That hasn’t resolved all of SpaceShipTwo problems, as seen by the slow pace of test flights. One newsworthy part of Schmidle’s book, which generated headlines when it leaked out earlier this year, is a problem on the February 2019 flight to space. Technicians preparing the vehicle for flight had covered with Kapton holes in its horizontal stabilizer, or h-stab, used to equalize pressure. With the holes blocked, pressure inside the vehicle created a wide gap in the right h-stab, compromising the structure. “I don’t know how we didn’t lose the vehicle and kill three people,” Todd Ericson, the company’s vice president of safety, recalled.

Virgin Galactic never publicly discussed this incident until after that portion of the book came out. Ericson left the company after the incident, and the company hasn’t released an independent report the board commissioned, at the behest of Ericson, about those safety issues. George Whitesides, the longtime CEO of Virgin Galactic who stepped down from that role last year and left the company entirely earlier this year, is not a major presence in the book beyond looking “stricken” when Ericson announced his resignation and other times showing a reticence to make tough decisions.

| Those pilots, Schmidle wrote, knew “not all flight-test minutes were created equal, how one minute at the controls of an analog rocket ship could say more about a pilot than thousands of hours in another vehicle.” |

Through all this Stucky is the book’s central figure, including both his flights—he was the pilot on SpaceShipTwo’s first flight beyond 50 miles altitude in December 2018—and his private life that included divorce and remarriage, and estrangement and rapprochement with his adult children. The book is also, a little bit, about Schmidle himself and his relationship with his father, also a Marine pilot. That helped open doors for this book project, as an old family friend was CJ Sturckow, a former Marine pilot and NASA astronaut now working at Virgin. Those doors closed, though, after Schmidle wrote a profile of Stucky and Virgin for The New Yorker that rankled some Virgin officials who thought it made the venture look too risky.

The book is also something of a celebration of test pilots—the “test gods” of the book’s title—and the skills they offer. Stucky had a bet with a fellow test pilot, Jack Fischer, about who would go to space first. Fischer, a NASA astronaut, won the bet when he went to the International Space Station on a Soyuz. When Stucky paid up with a dinner at a Mexican restaurant outside the gates of Edwards Air Force Base, it was Stucky that the other test pilots in attendance hailed for his feat piloting SpaceShipTwo to the edge of space. Those pilots, Schmidle wrote, knew “not all flight-test minutes were created equal, how one minute at the controls of an analog rocket ship could say more about a pilot than thousands of hours in another vehicle.” In other words, Fischer rode on a rocket to space, while Stucky flew a rocket to space.

Meanwhile, the waiting continues for Virgin Galactic. At an earnings call Monday, company executives said they believed they had solved the electromagnetic interference issue that aborted the December test flight, and that SpaceShipTwo was about ready to fly again. Except, they said, they found a potential “fatigue and stress” issue with the WhiteKnightTwo aircraft that carries SpaceShipTwo aloft, something discovered during a flight of the plane just last week. It was too soon, they said, to know if it will affect the schedule for the next SpaceShipTwo test flight.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.