Review: Beyondby Jeff Foust

|

| Beyond is not a grand political or technical history of the space race or of Gagarin’s flight, but instead much more of a story of the people involved with the competing efforts to launch the first human into space. |

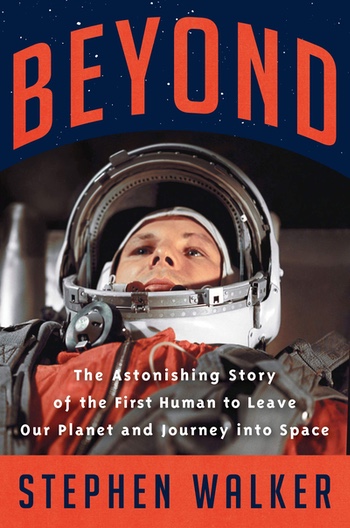

That is the dramatic theme of Beyond, a history of that race by Stephen Walker. The book’s subtitle (“The Astonishing Story of the First Human to Leave Our Planet and Journey into Space”) and the cover photo of Yuri Gagarin might lead one at first glance to think this is another biography of the famous cosmonaut. In fact, the book is a richly detailed account of the competing efforts by the Americans and the Soviets to be the first to launch a human, a race won by the Soviets and Gagarin in April 1961.

Walker’s book primarily covers the several months from late 1960 through Gagarin’s flight in April 1961 and Alan Shepard’s Mercury suborbital flight less than a month later. He goes back and forth between the deliberative American effort, taking place amid the start of the Kennedy Administration and its uncertain views at the time of human spaceflight, and the secretive Soviet effort that gained new urgency in the opening months of 1961 when it became clear they had a chance to beat the Americans. Throughout this narrative arc, though, he does dip back into history for biographical sketches of key individuals, like Gagarin and Sergei Korolev, or to summarize the development of Project Mercury and the selection of those first seven astronauts.

Despite the fact that this history is well known, Walker still offers a compelling story about the events of the time. The book doesn’t offer much in the way of major revelations about those events, but does turn those historical figures into dramatic characters. For example, see Gagarin, described throughout the book as a cheerful character, turn quiet and “self-controlled” on the morning of his flight, in the words of a doctor who examined him during pre-launch preparations. His backup, Gherman Titov, also went through the same pre-launch preparations, suiting up and going out to the pad with Gagarin just in case something unforeseen happened at the last minute to prevent Gagarin from flying. Only once Gagarin was in the Vostok capsule and strapped in was Titov told he could take off his suit; he would not be launching in Gagarin’s place. (Titov then proceeded to take a nap in the back of the bus that ferried them out to the pad, Walker writes; “he had barely slept all night.”)

Beyond is not a grand political or technical history of the space race or of Gagarin’s flight, although there is discussion of both politics and technology in the book. The book is instead much more of a story of the people involved with the competing efforts to launch the first human into space, one supported by the many interviews Walker did with people in both Russia and the United States. They become people you can root for, or against, despite knowing how the race will end.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.