The little satellite that couldHow a vice president’s dream led—after a very long delay—to the DSCOVR spacecraftby Dwayne A. Day

|

Vice President Al Gore at MIT in March 1998 calling for an Earth-looking satellite. (credit: Greg Kuhnen--The Tech) |

Dreaming of Earth

It was February 1998 and Vice President Al Gore had a dream. In his dream he saw a picture of Earth, a tiny blue-white ball against the vastness of space, spinning slowly, fragile. Gore already had an enlarged photo of the famous Apollo 17 image of the fragile Earth against the blackness of space on his office wall in the West Wing of the White House. He woke up at 3 am. The dream gave Gore an idea: what if a satellite imaged the Earth from far out in space, 24 hours a day? Could it show flow of the clouds, the changing of the seasons? Could such an image change the world, convincing people of the delicate nature of the planet they lived on?

After doing a little research on the Internet in the morning, Gore called Daniel Goldin, the NASA administrator, and told him about his idea. The satellite could be placed at a Sunward location known as L1 where the Sun’s gravity balances the Earth’s gravity. There it would have the Sun at its back and Earth would always appear in daylight. Goldin agreed to consider it.

| “I believe there is tremendous scientific value in having constant live television pictures of the Earth,” Gore told the Post. |

The story first went public in March 1998 in a front-page Washington Post article accompanied by a photograph of the Earth. Vice President Gore had clearly decided to give the newspaper an exclusive. The article stated that Gore was going to announce the satellite idea the next day during a speech at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Goldin told the Post reporter that he hoped to keep the satellite project’s cost below $50 million, and hopefully close to $20 million.[1]

“I believe there is tremendous scientific value in having constant live television pictures of the Earth,” Gore told the Post. “With the entire hemisphere in view, fully lit by the sun, scientists will be able to analyze weather systems and cloud patterns in ways they cannot today. With global warming a growing concern, and with problems like El Nino causing growing concern, this will be of tremendous value,” Gore said. [2] “I believe it will have an inspirational value that’s hard to describe,” he added.

According to the Post, the satellite idea was entirely Gore’s, and the vice president pushed it with fervor. Gore first told Goldin of the idea in mid-February and Goldin assigned two NASA scientists to work on it. On March 6, Gore informed Goldin that he was going to publicly announce the plan the following week, at which point Goldin assigned two more NASA scientists to the project. There was none of the normal scientific vetting of the mission common to most NASA science projects. “My head is still spinning,” Goldin said of the rapid pace (and perhaps the vice president’s fait accompli in announcing the project).

That same day, the White House issued a press release announcing the satellite plan.[3] Unnamed sources on Capitol Hill later chafed that Gore publicly announced the program before he had briefed Congress.[4]

Gore had a problem with the Post’s article, something that isn’t unusual for politicians. “I’ve never called to complain” about Post coverage before, Gore said when he called the newspaper’s executive editor. “But I thought about it and thought about it, and I decided I just had to call because you’ve printed a picture of the Earth upside down” on the front page of the newspaper. “Well, nobody else has called,” the editor, Leonard Downie Jr., responded. After hanging up the phone, Downie wondered what Gore could mean by “upside down.” After all, the picture was taken in outer space, where there’s no up or down.[5]

Speaking at the National Innovation Summit at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology the day after the story appeared, Gore said that the satellite would provide “a clearer view of our world” and have “tremendous scientific value.”[6] Gore used lofty language. “As Socrates said 2,500 years ago,” Gore said, quoting the Greek philosopher, “Man must rise above the Earth to the top of the atmosphere and beyond, for only thus will he understand the Earth in which he lives.”[7]

In addition to suggesting a name for the satellite, Gore also suggested calling the ground station “Earth-Span,” after the “C-SPAN” cable network that then devoted much of its time to reporting on the actions of Congress. The satellite was initially conceived to provide a satellite image that would be refreshed every few minutes.

The unorthodox genesis of the Triana satellite was guaranteed to earn it enemies. The project looked like the vice president’s multimillion-dollar vanity project. Was it proper to allow the vice president to spend tens of millions of dollars based upon a dream? Gore’s linkage of the project to global warming and its inspirational value was no help. Critics—and journalists—soon labeled the project “Gore-cam,” “Gore’s screen saver,” and “Goresat.”[8] One article poked fun at the idea of a television channel showing a live program starring the Earth, wondering what the show should be named, and who should co-star.[9] Headline writers had a field day, with one editorial referring to “Midnight Follies.”[10] The New York Times slammed the idea of staring at the boring Earth in an editorial titled “Like Watching Al Gore.”[11]

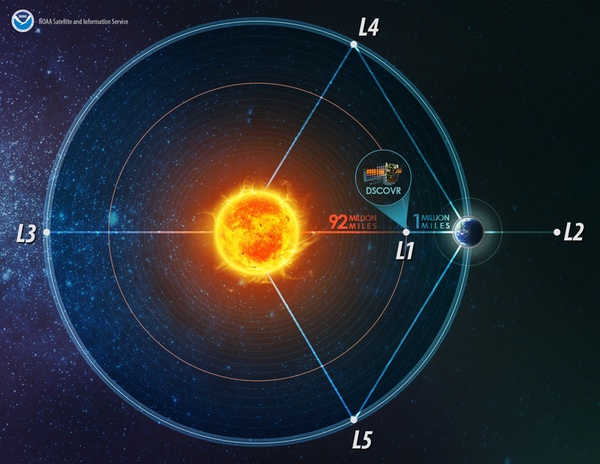

Graphic showing where the Triana satellite would be located in space, enabling it to continuously view the Earth's day side. Triana was later renamed DSCOVR. (credit: NOAA) |

Adding science

As the idea began to evolve at NASA, it morphed. The early concept was for a satellite that would largely be built by an academic institution, preferably by students. NASA’s Langley field center estimated that the spacecraft would cost $52 million to build, excluding launch, and JPL estimated that the mission would cost $96.5 million. NASA Headquarters’ initial goal of $20–50 million assumed that the spacecraft would involve substantial commercial participation to keep the costs down. But NASA officials began adding to Triana. Between April and July of 1998 the proposed spacecraft’s mass grew by 50 percent. At some point NASA officials decided that Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, not far from Washington, DC, would be responsible for overall management of the project. Goddard had traditionally been in charge of Earth sciences spacecraft.

In April 1998, NASA solicited proposals on other “educational, scientific or commercial applications,” for Triana.[12] The L1 location was particularly advantageous for other reasons. One person wrote a letter to Space News noting that the location was excellent for providing immediate observations of the solar wind, providing a warning of an hour or so of incoming shocks to Earth’s magnetosphere.[13] Others quickly picked up on the same point.

By July 1998 NASA issued an announcement of opportunity for scientific research on Triana. Scientists were encouraged to propose instruments that could be carried on Triana, although this would almost certainly boost its cost above the initial $50 million cap established by Goldin.[14] NASA received nine responses by the six-week deadline, and agency evaluators concluded that three were compliant.

| As the idea began to evolve at NASA, it morphed. The early concept was for a satellite that would largely be built by an academic institution, preferably by students. |

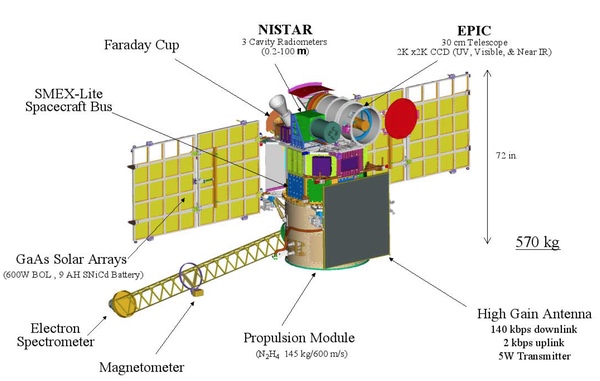

NASA soon selected a proposal from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography of La Jolla, California to include an upgraded camera and a radiometer. The primary instrument was the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC), to be built by Lockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center of Palo Alto, California. EPIC would provide global spectral images of the sunlit side of the Earth with wavelengths spanning the ultraviolet and the near infrared. The four-megapixel CCD array would be sensitive over the entire wavelength with a resolution of 8–14 kilometers. EPIC would measure global ozone levels, aerosol index and aerosol optical depth, cloud height over land and ocean, vegetation index and leaf area index, ultraviolet surface radiation, and aerosol and ozone plume tracking.

The satellite would also carry a radiometer known as NIST and used for studying the solar wind. NIST would provide Earth radiation data from a four-channel radiometer from the visible to the far infrared. NIST would measure ultraviolet, visible, and infrared reflected solar irradiance. A magnetometer was also proposed by Goddard Space Flight Center. NIST would be built by Scripps, and along with the magnetometer would observe protons, helium ions, and electrons that form the solar wind.[15] The instruments now made Triana a real science spacecraft, not just a fancy screen saver. To accommodate these new instruments, NASA added $27 million to the $50 million budget, making Triana a $77 million spacecraft.

NASA sought to keep Triana costs down by using spare components from previous programs, including a hydrazine tank from the Cassini spacecraft, sun sensors, omni antennas, and other parts. NASA sought to acquire an Italian Research Interim Stage for boosting Triana from low Earth orbit to its operational orbit. The agency originally hoped to obtain the IRIS in exchange for NASA launching a future Italian satellite.

NASA at that time planned on using a spacecraft design known as SMEX-Lite. It was essentially cylindrical, with two solar panels extending outward and a large high-gain antenna mounted on the centerline with a single imaging instrument mounted alongside, with both antenna and telescope pointing at the Earth.[16] By December 1998, Triana’s primary science objective was to “provide continuous imaging of the Full Earth Disk with a spatial resolution of 5 kilometers and a temporal scale of ten minutes.” The mission lifetime was five years.

Triana’s science goals were to answer some fairly broad questions: How much ultraviolet radiation from the Sun reaches the Earth’s surface and how does it vary through each day as a result of ozone and other changes? How can aerosols in the atmosphere be measured, both for use in climate research and to provide hourly updates on ground level visibility and aerosol plumes for aircraft routing and other purposes? Can the unique view of Triana be used to improve our understanding of cloud microphysical properties? How much solar energy is absorbed in the Earth’s atmosphere? Can we provide rapid warning of solar flares and other extreme solar events to allow utility companies and satellite operators timely and effective warning?

Because the SOHO Sun-observing spacecraft was considered to be on its last legs, NASA added the desire for Sun-observing equipment to the Triana request for proposals a week after issuing it. According to an unnamed Capitol Hill staffer, one possibility was to build a SOHO follow-on, add a Triana camera to the back of the spacecraft so that it was looking at Earth while the rest of the instruments looked at the sun, and rename the sun-observing spacecraft “Triana” to technically fulfill the Gore mission. “There is concern that the haste to make the Vice President’s year 2000 political schedule could result in loss of the SOHO follow-on payload or mission, which would be tragic,” the unnamed source explained.[17] Although nobody knew it at the time, SOHO proved to be far more long-lasting than it was designed for, and the spacecraft is still operating today and may last to 2025, three decades after launch.[18]

Triana spacecraft showing its instruments and overall configuration. (credit: NASA) |

Political controversy

In summer 1998, shortly before NASA issued its announcement of opportunity for additional instruments, the House Appropriations Committee, which was controlled by Republicans, eliminated all funding for the spacecraft. The committee report stated: “Because the program’s focus is not clear, and the proposal has not been peer reviewed, the committee directs that no funds be expended for feasibility studies or satellite procurement associated with the mission.”[19]

| In May 1999, with Gore now running for president, Triana was clearly in political trouble. |

But it was not only Republicans who were critical of Triana. Pat Dasch, executive director of the National Space Society, wrote an op-ed questioning the project.[20] Trade industry newspaper Space News published an editorial that noted that the Clinton administration had reduced NASA’s spending power by 40% during the previous six years and Triana was an unscientific waste of money.[21] John Pike, of the Federation of American Scientists, said “We can already see pictures like that from weather satellites. They’re pretty boring. It’s like watching the grass grow.”[22] A column in Insight Magazine referred to Triana as “exquisite foolishness” and criticized Goldin’s willingness to salute smartly and promptly assign people and money to the project. The author suggested instead that the NASA administrator should have followed the same principle that Disraeli used to respond to goofy ideas from Queen Victoria: “I never deny, I never contradict,” Disraeli explained. “I sometimes forget.”[23]

Although the House Republicans had zeroed out Triana’s funding, NASA had decided that the satellite would be built at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, and Senator Barbara Mikulski, who represented the state, managed to restore the funding. A former Goddard director used to keep a photo of Mikulski on his door and regularly referred to her as “the Queen” for her patronage of the NASA center.

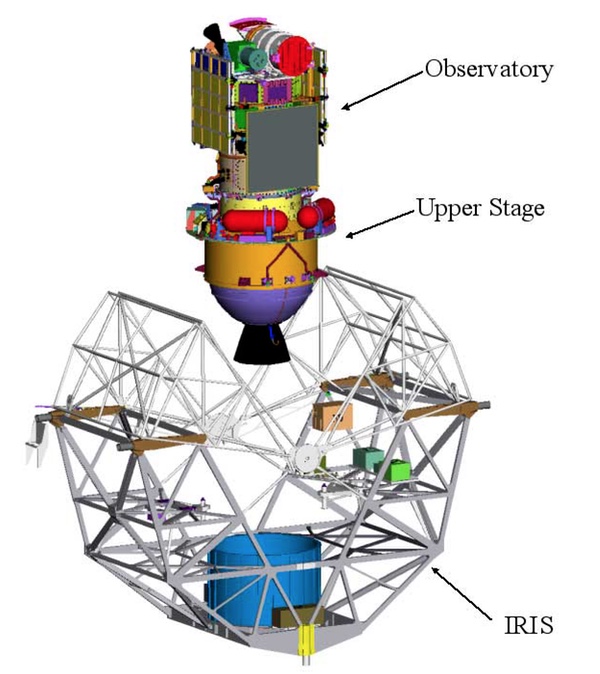

Triana and its upper stage were intended to be deployed from the space shuttle Columbia's payload bay during the STS-107 mission. But delays, and political controversy, led to Triana's removal from the shuttle manifest. (credit: NASA) |

Launch controversy

In May 1999, with Gore now running for president, Triana was clearly in political trouble. Republicans deleted funding for the project as part of the NASA funding bill then working its way through the Congress. The satellite program was already planned to spend $41 million by the end of the year. Officially, it was scheduled for launch in December 2000, conveniently only one month before the inauguration of the next president. Accusations quickly began flying in Congress, with both Republicans and Democrats accusing the other of “politicizing” the issue. Two Republican congressmen proposed transferring $32.6 million for Triana to NASA life and microgravity research instead, and there was talk of President Clinton vetoing the NASA budget if Triana was eliminated.[24]

From the beginning, NASA had decided that Triana would be launched by the Space Shuttle, and in November 1998 the agency sought to have it placed on the manifest for a shuttle launch as a “secondary payload,” meaning that it would fly if there was available room on an upcoming shuttle flight. But as Triana progressed and became heavier and more complex, the satellite started to appear less like a secondary payload and more like a primary one. This conflicted with the Commercial Space Act of 1998, which directed the government to purchase space transportation services from the commercial sector to the maximum extent possible.

As initially conceived, Triana could have flown aboard a Taurus rocket, but as its mass increased it quickly outgrew that vehicle and would have required a Delta II. Triana and its support equipment added 9,000 pounds (4,082 kilograms) of mass to the shuttle payload, a major portion of its launch capability. In addition, Triana required a special orbit and other operational considerations in order to reach its L1 orbit. Thus, Triana could not be launched aboard shuttle flights to assemble the International Space Station.[25] By this time, Triana was the most complex shuttle payload ever assembled at Goddard.

More criticism, and a reprieve

In summer 1999 the NASA Inspector General began a review of the Triana mission and by September it produced its report.[26] The report noted that “a relatively simple and inexpensive mission focused primarily (though not exclusively) on inspiration and education has evolved into a more complex mission focused primarily on science.” The report noted that NASA had peer reviewed the science that was added to the mission, but that the parameters had been decided beforehand, and the schedule for soliciting and reviewing proposals was compressed, limiting the number and variety of submitted concepts.

The report noted that “NASA’s major role in developing and launching the spacecraft does not further the goals of the National Space Policy of 1996 and the Commercial Space Act of 1998, which direct NASA to acquire spacecraft and launch vehicles from the private sector whenever possible.”

The report suggested that NASA “reassess its current approach to the Triana mission” and consider several options, including: launching on a commercial launch vehicle and maximizing the mission’s scientific and educational potential; re-scoping the mission to reduce its cost and maximize its educational and inspirational component, perhaps by deleting some of the spacecraft’s scientific capabilities and/or changing the spacecraft’s orbit; or conducting a “Virtual Triana” mission “using data from the numerous spacecraft already transmitting pictures of the Earth”—without launching Triana itself.

But the part of the Inspector General’s report that attracted the most attention was a new estimate of the cost: whereas Goldin had initially stated that Triana could cost as low as $20 million, the mission cost had now grown to almost ten times that amount. The NASA IG report received substantial media coverage, most of it focusing on its statement that Triana would now cost much more than the original cost goal.[27]

The House Conference Report accompanying the fiscal year 2000 NASA appropriations bill stated “The conference have not terminated the Triana program as the House had proposed. Instead, the conferees direct NASA to suspend all work on the development of the Triana using funds made available by this appropriation until the National Academy of Sciences has completed an evaluation of the scientific goals of the Triana mission.” The report further stated that even upon receiving a favorable report from the National Academy of Sciences, “NASA may not launch Triana prior to January 2001.”

Congress put Triana on hold while it awaited the NRC study.[28] The launch date and whether it was before or after the election was a constant source of commentary.[29]

| Whereas Goldin had initially stated that Triana could cost as low as $20 million, the mission cost had now grown to almost ten times that amount. |

The National Research Council (the operating arm of the National Academy of Sciences) created a “Task Group on the Review of Scientific Aspects of the NASA Triana Mission” in December 1999, chaired by James Duderstadt of the University of Michigan. The group met in January 2000 and heard various presentations from NASA, NOAA, industry, and academic experts.[30] After deliberating, writing a report, and putting it through peer review, the committee publicly delivered its report to NASA.

The NRC report addressed several questions that were posed to the committee. It stated, “In general, the task group found that the scientific goals and objectives are consistent with the strategies and priorities for collection of climate data sets, and the need for development of new technologies, as articulated in relevant reports published by the National Research Council and other similar organizations.” The committee added that they could not find any specific recommendation for using the L1 point in previous NRC reports, but added that the location offered the potential “to integrate data from multiple spaceborne as well as surface and airborne observation platforms into a self-consistent global database for studying the planet and documenting the extent of regional and global change.”[31]

The committee noted that the plasma-mag instruments on Triana were planned to make the same measurements that had been made previously and were then being made on both the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) and the Solar Wind Observatory (WIND) spacecraft. However, the Triana instruments have a 30-fold improvement in the time resolution of the solar wind ion measurements

The group recommended that “NASA seriously consider increasing the level of effort invested in development and testing of data reduction algorithms for the core Earth data products as soon as possible and ensure that all the appropriate technical and management reviews are performed.”[32]

Finally, the committee concluded that Triana’s cost was “not out of line for a relatively small mission that explores a new Earth observing perspective and provides unique data.” Because 50 percent of the total funding and 90 percent of instrument development money had already been expended, canceling the project and redirecting the money was unlikely to substantially help other projects.[33]

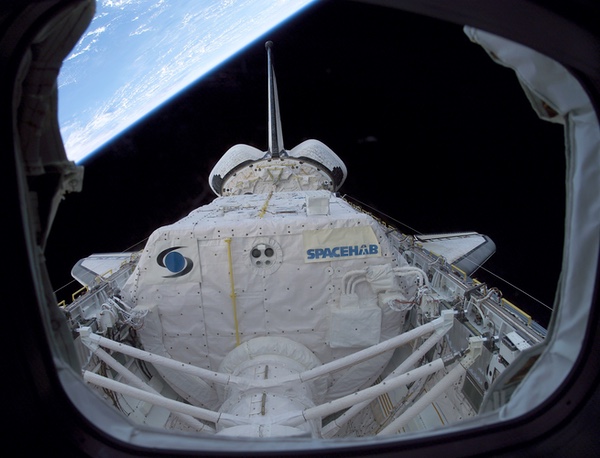

Spacehab in the Columbia payload bay during the ill-fated STS-107 mission. At one point, the Triana satellite was slated to be carried aboard STS-107 in 2001, mounted behind the Spacehab module. However, delays in Triana development slipped it off the manifest. The STS-107 mission slipped multiple times, eventually launching in early 2003. (credit: NASA) |

More launch woes

By April 2000, Triana was scheduled for launch aboard the space shuttle Columbia during mission STS-107, scheduled to launch no earlier than February 22, 2001. By July 2000, the STS-107 launch date had slipped to June 2001. But Triana would still not be ready by that time. NASA officials claimed that the five-month standdown while the agency awaited the response of the National Research Council study, coupled with months of additional testing mandated by the report, had now pushed it beyond the scheduled launch date for STS-107.[34]

But the controversy surrounding a shuttle launch as opposed to a commercial rocket remained. In February, a lawyer working for the Congressional Research Service noted in a letter to Congressman George R. Nethercutt, Jr. that the shuttle plan likely violated the Commercial Space Act.[35]

In 2001, only a few months after the inauguration of George W. Bush, as Triana was being prepared for transport to the launch site, the launch was put on hold. In March, NASA announced that because the new budget was limiting the agency to six shuttle missions per year, they were unable to identify a launch for Triana.[36] By April 2001, the spacecraft was grounded, ostensibly because of massive cost growth in the International Space Station project. The head of NASA’s Earth science program authorized $24.9 million to finish remaining work on the spacecraft so that it could be placed into a “stable state of suspension.”[37]

With a Republican president in the White House, his Democratic opponent’s dream project was sent into exile.

Endnotes

- Kathy Sawyer, “The World, Live – Just a Click Away,” The Washington Post, March 13, 1998, p. A01.

- Ibid.

- Office of the Vice President, “Vice President Gore Challenges NASA to Build a New Satellite to Provide Live Images of Earth From Outer Space,” March 13, 1998.

- “Tough Sell,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, March 23, 1998, p. 21.

- “Gore’s Concern about Earth,” The Washington Post, March 16, 1998, The Federal Page.

- Bill Donahue, “Who Killed the Deep Space Climate Observatory?” Popular Science, April 6, 2011.

- “Gore proposes satellite to provide live video of Earth 24 hours a day,” Dallas Morning News, March 14, 1998, p. 7A.

- Frank Sietzen, “Critics question value of Gore satellite,” United Press International, March 13, 1998; “Scripps Institution, GSFC picked to put ‘Goresat’ at L-1 point,” Aerospace Daily, October 29, 1998.

- “Planet Earth to become a television show?” Florida Today Space Online, Associated Press article, March 18, 1998.

- “Midnight Follies,” Space News, March 23-29, 1998, p. 14.

- “Like Watching Al Gore,” The New York Times, March 18, 1998, p. A26.

- “NASA seeking proposals on L-1 satellite,” Aerospace Daily, April 7, 1998, p. 35.

- Jim Secan, “Triana Possibilities,” Space News, April 6-12, 1998, p. 22.

- “NASA ‘encourages’ outside contributions, data buys for Triana,” Aerospace Daily, July 15, 1998, p. 77.

- “Goddard Contributes to Recent Spacecraft and Science Selections,” Goddard News, Vol. 2, No. 47, November 1998, p. 1; “Scripps to lead $75 million mission to study Earth from space,” Scripps Institution of Oceanography Press Release, October 27, 1998.

- “Triana Attitude and Orbit Control System Concept Overview,” GNCC, Code 570, December 15, 1998, p. 6. This set of briefing slides was apparently intended for an internal NASA briefing.

- Michael A. Dornheim, “Soho Calls Home, But Health Unknown,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, August 10, 1998, p. 816.

- Debra Werner, “U.S. government aims for better coordination in space weather campaign,” Space News, March 25, 2020.

- “No to Triana,” Aerospace Daily, Vol. 186, No. 63, June 29, 1998, p. 1.

- Pat Dasch, “Triana: The Stuff of Dreams,” Space News, June 22, 1998.

- “Wasting Money on Triana,” Space News, October 12, 1998.

- Nigel Hawkes, “Is it Down to Earth, Al?” The Times of London, June 1, 1998.

- Woody West, “Gore Reinvents Capriciousness,” Insight Magazine, April 5, 1998, p. 49.

- Juliet Eilperin, “House GOP to Gore: No Room for this View,” The Washington Post, May 19, 1999, p. A4.

- “Possibility of Launching Triana on an ELV,” (Space and Aeronautics Subcommittee Questions), April 2000.

- Inspector General, NASA, to Administrator, “Assessment of the Triana Mission, G-99-013, Final Report,” September 10, 1999.

- “NASA IG counts tenfold increase in Triana mission cost,” Aerospace Daily, September 15, 1999.

- Otto Kreisher, “Congress postpones Scripps satellite project,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, October 20, 1999, p. B-2.

- Larry Wheeler, “Gore’s satellite slated for launch month after 2000 elections,” Gannett News Service, April 8, 1999.

- “Report of the Task Group on the Review of Scientific Aspects of the NASA Triana Mission,” National Research Council, March 2000.

- Ibid., p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 11.

- Ibid., 18-19.

- Brian Berger, “Satellite Delays Push Triana Launch to 2002,” Space News, July 31, 2000.

- John R. Luckey, American Law Division, Congressional Research Service, to Honorable George R. Nethercutt, Jr., “The Commercial Space Act of 1998 and the Launch of the Triana,” February 1, 2000.

- Brian Berger, “No Flight Date for Triana,” Space News, March 20, 2001.

- Frank Morring, Jr., “NASA Mothballs ‘Goresat,’” Aviation Week & Space Technology, April 2, 2001, p. 23.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.