Starliner sidelinedby Jeff Foust

|

| “I think this flight is going to go very well,” Nelson said July 29. |

Next up were the three NASA astronauts who will be on the first crewed flight of Starliner, the Crew Flight Test (CFT), along with Boeing official and former NASA astronaut Chris Ferguson, who originally was to be on that mission but stepped aside last year because of personal schedule conflicts, at the time when the mission was expected to launch in mid-2021.

“It’s been a long time preparing for this flight,” Ferguson said, recounting the work done since the first, flawed OFT mission in December 2019. “We’ve very proud to be conducting our second flight. We will be equally proud when we launch the awesome CFT crew here later this year. It’s going to be a great day.”

Within hours, those plans were thrown for a loop—literally. The press conferences took place shortly after the long-delayed Nauka module docked with the station. Three hours after docking, the module’s thrusters started firing, causing the station to lose attitude control and do one and a half loops before ground controllers were able to stabilize the situation.

Later that day, NASA decided to call off the July 30 launch attempt for OFT-2 to make sure everything was under control and that the incident didn’t cause damage to the station. “We want to ensure the space station is in a stable configuration and ready for Starliner to arrive,” Steve Stich, NASA commercial crew program manager, said in a call with reporters a few hours after the ISS incident.

The Atlas V rocket carrying Starliner rolled back to its Vertical Integration Facility (VIF), taking it out of the elements to await the next launch. With the all-clear from the station, the rocket rolled back out to the pad August 2 for a launch scheduled for 1:20 pm EDT August 3. Everything seemed set for a launch… until Boeing announced three hours before liftoff that the launch was scrubbed.

The problem, the company said, involved “unexpected valve position indications in the propulsion system” in the spacecraft. That phrase, along with a comment that the problem was detected in tests after a severe thunderstorm the night before, suggested that the issue may have been with the vehicle’s electronics. Had Boeing, after its extensive review of the software that caused problems on the first OFT mission, missed something?

Over the next several days, it became the clear the problem was with the valves themselves and not software. By August 9, Boeing revealed that 13 valves in Starliner’s propulsion system did not open when commanded to do so during prelaunch checkouts. Technicians, able to access the spacecraft again after the Atlas V rolled back to the VIF a couple days after the scrub, were “applying mechanical, electrical and thermal techniques to prompt the valves open,” the company said in a statement.

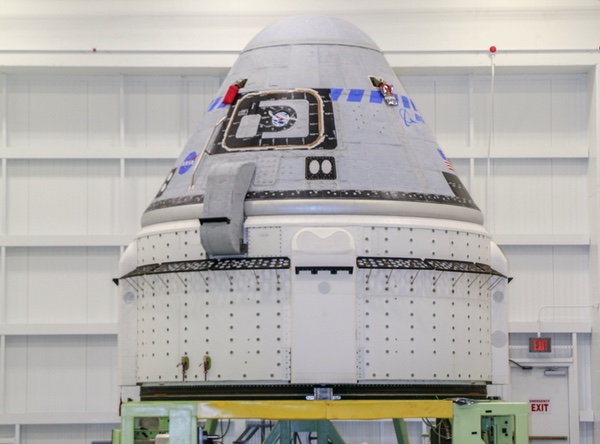

The Atlas V with Starliner at the pad August 2, just before the launch was scrubbed because of problems with the spacecraft. (credit: NASA/Joel Kowsky) |

The company never set a new launch date after the August 3 scrub, but kept open the chance of still launching the spacecraft later in the month. “The company is assessing multiple launch opportunities for Starliner in August and will work with NASA and United Launch Alliance to confirm those dates when the spacecraft is ready,” Boeing said August 9.

| The nitric acid corrosion “is our leading candidate for what has caused the issues with the valves,” Vollmer said. |

Four days later, it threw in the towel. Just before a NASA media call on Friday, August 13, Boeing said it would remove Starliner from its Atlas V and return the spacecraft to its Commercial Crew and Cargo Processing Facility, a former shuttle processing hangar at the Kennedy Space Center where Boeing assembles Starliners. Any chance of a launch in August, or for months to come, was now off the table.

At the briefing, John Vollmer, vice president and program manager of Boeing’s commercial crew program, said the most likely cause of the stuck valves involved nitrogen tetroxide (NTO) propellant permeating the Teflon seals of the valves. The NTO then interacted with moisture on the other side of the valve, creating nitric acid that corroded the valve and caused “stiction” that kept the valves closed even when commanded to open. Similar valves used for fuel and helium pressurant showed no problems.

“Now, we’ve got a lot of things on the fault tree” of potential causes to examine, he said, “but, right now, that is our leading candidate for what has caused the issues with the valves.”

Technicians had been able to get nine of the 13 valves working again, and Vollmer noted that, once the valves opened, they worked properly, opening and closing on command. It could not, though get the other four working before deciding to destack the spacecraft and return it to the factory. “We made the decision that we were just out of runway and we had to come back to the factory to complete anything else we needed to do,” he said.

One uncertainty is the source of the moisture in the propulsion system that interacted with the NTO to create the nitric acid. Vollmer said the company couldn’t rule out having the moisture present in the thrusters since they were installed on the spacecraft, or later, once the spacecraft was exposed to the humid Florida air. Before the August 3 scrub, the valves were last checked in June when the spacecraft was fueled and were working well. The same valves were used without any problems on both the first OFT flight as well as Starliner’s pad abort test at White Sands, New Mexico, in November 2019.

Vollmer did, though, appear to rule out any water intrusion from the storm the night before the scrubbed launch as a cause of the problem. The storm did cause some erroneous sensor readings from the spacecraft, he said, but didn’t cause the valves to stick. “The moisture we saw in the valve is atmospheric moisture. It is not intrusion moisture,” he said.

| “It’s probably too early to say whether it’s this year or not,” Vollmer said. “We would certainly hope for as early as possible. If we could fly this year it would be fantastic.” |

Vollmer offered no schedule for fixing the valve problem. The spacecraft, once returned to its processing facility, will be closely examined. “Our intent will be to disassemble as little as possible so we can minimize any changes to the configurations,” he said. For example, it’s uncertain if Boeing will need to replace all the valves in the spacecraft’s propulsion system, including those working normally.

Evne if there was an immediate fix to the problem—an unlikely scenario—OFT-2 will still be on hold for months. Starliner is designed to dock at one of two ports on the ISS, one of which is occupied by the Crew Dragon spacecraft that brought the Crew-2 astronauts to the station. On August 28, a cargo Dragon spacecraft will launch to the station, occupying the other port for about a month.

In the meantime, ULA will be getting ready for its next Atlas V launch, of NASA’s Lucy mission to the Trojan asteroids accompanying Jupiter in its orbit around the sun. That mission has a three-week launch window that opens in mid-October. Only after it launches could the Atlas V be prepared for OFT-2, if the Starliner is ready. And, in the interim, the Crew-3 mission will launch at the end of October on another Crew Dragon spacecraft, with Crew-2 returning a week or so later.

Vollmer declined to say even if Starliner would be ready to fly before the end of the year. “It’s probably too early to say whether it’s this year or not,” he said. “We would certainly hope for as early as possible. If we could fly this year it would be fantastic.”

NASA officials on the call sounded disappointed, in part because they appeared so close to flying OFT-2. “You might be hearing us sound a little tired, because teams have been working really hard, but we’re not frustrated,” said Kathy Lueders, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations. “I’m a little sad, because I wanted to go fly, but I’m also very proud of the team.”

“It’s a bit of a disappointing day. We’re all looking forward to flying the OFT-2 test flight and testing out the systems on the vehicle, so it is disappointing that we’re not going to have this opportunity in the August timeframe,” Stich said.

Nothing in the NASA comments suggested they were giving up on Boeing, despite the extended delays in development of Starliner. But the latest delay means that NASA will have to continue to rely exclusively on SpaceX for getting astronauts to and from the station likely through next year, depending on exactly when OFT-2 and CFT are certified. It’s a far cry from a few years ago, when NASA was planning to extend CFT from a brief test flight to potentially a six-month stay on the ISS, thinking it would be ready ahead of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon to end reliance on Soyuz.

| “When this competition for commercial crew started, what if we hadn’t had two competitors, and what if it had only been Boeing?” asked Nelson. |

It fits into a broader perception that Boeing has somehow lost its technical edge, given other problems in military and civilian aviation, like the 737 MAX. For example, Vollmer noted that the moisture in the propulsion system could have come from the humid Florida air. “Our last flight was in December, so it a totally different kind of atmospheric conditions,” he said. The fact that conditions in Florida are humid in summer—much of the year, really—is hard to overlook.

While agency officials say they’re not frustrated with Boeing, it’s hard not to notice some degree of frustration in general with Boeing’s delays. At that July 29 briefing, Nelson made the case for competition in the Human Landing System program despite a lack of funding for more than one provider. “What it does is it gives you a backup,” he said of competition. “When this competition for commercial crew started, what if we hadn’t had two competitors, and what if it had only been Boeing?”

For now, NASA can only wait while Boeing diagnoses and corrects the problem. In the briefings leading up to the scheduled OFT-2 launch, Boeing had emphasized they had found and corrected all the software and communications issues from the original OFT test, and NASA agreed those issues had been resolved. Now, there may be nagging doubts if Boeing has truly found all the issues with the spacecraft.

“It’s extremely important to us that we’re successful on this flight. With all that we’ve done over the past 18 months, we are very confident that we are going to have a good flight,” Vollmer said at a briefing last month. “It is of paramount importance that we have a successful flight.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.