Cooperation, competition, conferences, and COVIDby Jeff Foust

|

| “We expect our Russian partners to continue with us, and we expect to expand the space station as a government project all the way to 2030,” Nelson said. |

But there were also the masks required by conference organizers, a reminder that the pandemic, which some hoped earlier this year would be fading away by now thanks to vaccines, was still with us. Attendance was smaller than in recent years, in part because of the decision to hold it as a “hybrid” event with sessions livestreamed. (Virtual attendees, though, were on their own for networking.)

In the weeks leading up to the event, some major organizations pulled back given the concerns about the delta variant of the coronavirus. “General John Raymond and I have made a decision to cut back considerably, because of this delta variant of COVID,” NASA administrator Bill Nelson said in an interview the week before the conference, referencing the head of the US Space Force. Nelson said his deputy administrator, Pam Melroy, and his associate administrator, Bob Cabana, would stay at home.

“However,” he added, “I’m planning to go because there are a number of meetings with our international partners. Those will go on as planned, although the international delegations are considerably cut back as well.”

Indeed, the traditional heads-of-agencies panel at Space Symposium last Wednesday, which in recent years had swelled to an almost unmanageable size, was slimmed down at this year’s event. Nelson shared the stage with the leaders of six other national space agencies—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom—and the European Space Agency for a panel discussion.

The hour-long discussion, though, was enough to make clear Nelson’s views on international cooperation. It’s one where the traditional International Space Station partners continue to work together there while looking ahead to the Moon. It’s also one that plays down any rift with Russia while playing up a perceived space race with China.

“Despite what you read in the press, I think that the cooperation with the Russians, which has been there ever since 1975” will continue, Nelson said in his opening remarks on the panel. He saw a thread of cooperation going back to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975 that he expected to continue.

Proof of that, he said, was Russia’s decision to launch its long-delayed Nauka module to the station last month, rather than hold it back for a Russian space station that Roscosmos officials have talked about in recent months. “So what you’re hearing in the press is not necessarily true,” he said, not elaborating on what specific media reports were incorrect.

“We expect our Russian partners to continue with us, and we expect to expand the space station as a government project all the way to 2030, and we hope it will be followed by commercial stations,” he added.

| “Personally, I would strongly support it,” ESA’s Aschbacher said of extending the station. |

Nelson has long advocated for an extension of the ISS through the end of the 2020s, an effort that dates back when he still served in the US Senate. But a NASA decision to extend the ISS does little good if the other partners have little interest in doing so.

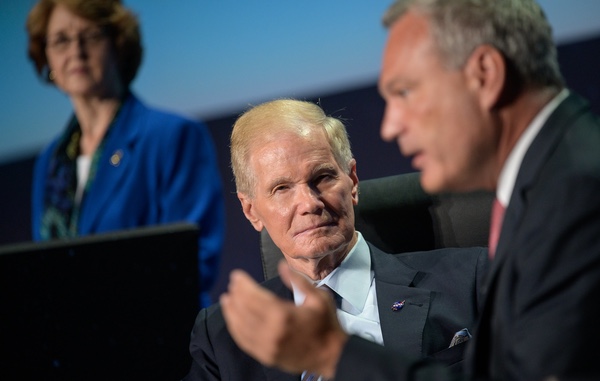

Nelson looks on as Walther Pelzer, head of the German space agency DLR, speaks during the Space Symposium panel. (credit: NASA/Bill Ingalls) |

Fortunately for Nelson, there is interest among other partners in an extension. “ISS is, from our point of view, tremendous infrastructure,” said Walther Pelzer, head of the German space agency DLR, in comments immediately after Nelson on the panel.

“It is a political statement that we can work together and, from this point of view, it has been and will be something that Germany will support as long as possible,” he said. “We are very happy that NASA is going in the direction of 2030.”

Germany is one of the largest member states in ESA, and its interest in the ISS will be a key factor in continued European participation beyond 2024. “Personally, I would strongly support it,” Josef Aschbacher, director general of ESA, said of extending the station during an interview at the Space Symposium.

That decision, though, would have to be made by ESA’s member states, most likely at their next ministerial meeting in late 2022. “I would certainly be very happy to present them a proposal for extended use of the ISS” at that meeting, he said.

Later in the panel, the question of cooperation with China came up. Nelson dived right in. “Unfortunately, I believe we’re in a space race with China,” he said. He’s offered similar comments in the past, such as a congressional hearing in May when he called China a “very aggressive competitor” while brandishing a photo of China’s Zhurong rover on Mars (see “Red planet scare”, The Space Review May 24, 2021).

Those comments, though, were primarily for domestic audiences, where the threat of a space race might encourage Congress to increase NASA’s budget. Here, he was speaking with representatives of other space agencies, particularly those in Europe that have shown a somewhat greater interest in cooperating with China on space activities.

None of the other panelists, though, explicitly disagreed with Nelson about a space race. Aschbacher noted that ESA had received an invitation from China and Russia to participate in those nations’ International Lunar Research Station (see “A shifting balance of space cooperation?”, The Space Review, June 21, 2021).

Aschbacher said that ESA had not taken any action to either accept or decline the invitation. “The offer is on the table, but what do I do with that?” he said. “Of course, I discussed this with my member states because they are governing ESA and they are the ones making the decision collectively in on board. This is a debate that is going on right now.”

However, then went on to emphasize ESA’s close relationship with NASA. “It’s the strongest partner with which we work and so well established over decades,” he said. “This is something I value extremely highly and I reassured NASA just two days ago that I want to lead forth the cooperation we have with NASA.”

| “But China is very secretive, and part of the civilian space program is that you’ve got to be transparent,” Nelson said. “So, I’ll just put that right out there.” |

The closest to criticism of the space race model was from Philippe Baptiste, chairman and chief executive of the French space agency CNES. He also emphasized his agency’s close relationship with NASA. “But let me play, perhaps, a naïve guy here,” he said, suggesting a model closer to high-energy physics where there is more international cooperation. “At CERN, all countries all over the world are involved if they want to. It’s completely open. They all work together to discover new particles. Their motto is, ‘peace by science.’”

Nelson, in his comments, appeared to open the door for cooperation with China. “I would like, speaking on behalf of the United States, for China to be a partner. I’d like China to do with us, as a military adversary, like Russia has done,” he said, cooperating in space despite conflicts on Earth, as the US and the former USSR did during part of the Cold War.

He almost immediately closed that door, though. “But China is very secretive, and part of the civilian space program is that you’ve got to be transparent,” he said. “So, I’ll just put that right out there.”

The panel featured no Russian or Chinese officials to offer their own views on cooperation or the future of the ISS. (Both Nelson and the head of Roscosmos, Dmitry Rogozin, have said they plan to meet in person, perhaps in Russia, this fall.) China and Russia are likely to participate in two months at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Dubai, where they can weigh in on cooperation and competition; Rogozin used last year’s online-only version of the conference to effectively rule out Russian participation in the NASA-led lunar Gateway.

That is, assuming the conference goes on. At the Space Symposium, there was chatter about whether IAC 2021 will go ahead given the surge of COVID-19 cases caused by the delta variant. Neither the space industry nor society in general are back to normal, no matter how reassuring one conference looked.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.