Engineering the arts for space: developing the concept of “mission laureates”by Christopher Cokinos

|

| In brief, mission laureates would create work inspired by missions—robotic and crewed—for wider public engagement. |

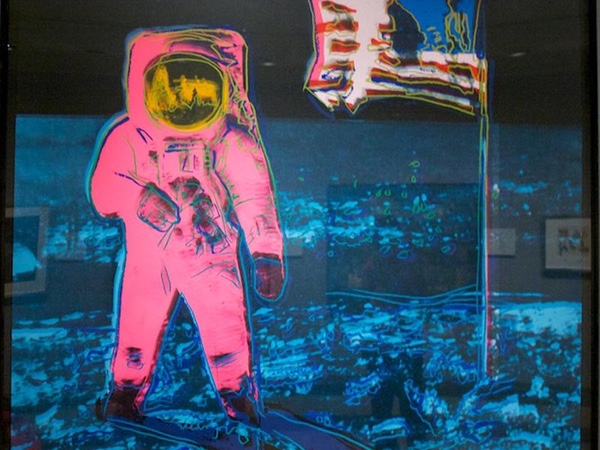

A fine overview of NASA, ESA, and the visual arts can be found in Dr. William A. Bezouska’s paper for The Aerospace Corporation, “Space and Art: Connecting Two Creative Endeavors.” His focus, as has been the focus of most art-space ventures, is strictly with the visual, from Apollo 15’s Fallen Astronaut memorial to various imagery, from large installation work to film, from classroom displays to art contests. And, of course, we await the possibility of the SpaceX dearMoon mission, in which artists will be billionaire-curated for a lunar orbital flight.

Yet other arts have gotten the short shrift: ceramicists, say, or modern dancers or textile artists. Or, in my case, poetry, though listing the number of real and fictional aerospace figures who have called on poets to be launched in space would take some time. (It’s interesting to note that at least two astronauts have come back from space to write poetry, Story Musgrave and Alfred Worden, both of whom are represented in Beyond Earth’s Edge.)

In the coming months, I hope to address more aspects of a vigorous, wide, multidisciplinary arts/space effort, including a call for all-artist analogue missions. (I’ve even submitted, and received an enthusiastic reply, for just such a mission proposal to an analogue facility being developed at Biosphere 2.) But here I want to concentrate on one specific suggestion for increased systematic arts engagement in space activities: mission laureates.

Mission laureates

The term “laureate,” of course, refers to someone who receives an honor, deriving from the ancient Greek tradition of placing a laurel wreath on the head of the honoree. The laurel tree was sacred to the god Apollo, patron deity of poets. In more recent history, countries such as Great Britain and the United States have had offices of poet laureates, a tradition that has spread to states, cities, and towns. The poets are asked to engage the public by presenting outward-facing work for non-literary audiences.

Here I want to argue for a new kind of laureate, one attached not to a region but to a mission, specifically missions to space. In brief, mission laureates would create work inspired by missions—robotic and crewed—for wider public engagement.

| If we are to engage and even inspire the wider public, the space community needs more organized approaches to positive artistic engagement with missions and science. |

I am not calling for art that is propaganda—a danger with laureates in the past—but, rather, work that provides new and exciting perspectives that can link a mission to wider currents in human affairs. It’s likely that artists interested in this opportunity will be pro-space but they surely will bring the nuance and complexity that we all need in confronting the paradoxes, promises, and perils of the human endeavor in space. The philosophical foundation is that aesthetics—from imagery to metaphor, from movement to symmetry, from surface texture to visual field—all matter enormously to humans. Here we tie aesthetics to communicating wonder, possibility, and betterment to audiences beyond the space community, audiences that consistently react with, at best, short-lived interest in missions or, more often, with consistent apathy, audiences that also rank crewed missions to the Moon and Mars at the bottom of space-priority opinion surveys.

Arguments about the evolutionary origins of art-making aside, we just do make art—and we do so out of a need to defy mortality and to create “I-Thou” bonds to use Martin Buber’s phrase, connections to other people, and even with non-human agents. In this vein, artists might be able to better articulate the green dream at the heart of space exploration and settlement, a long tomorrow of justice and sustainability for the Earth and beyond; a dream that is hard for the public to hear, let alone take seriously, from the often-narrow demographics of the space advocacy community and certainly from present-day billionaires.

If we are to engage and even inspire the wider public, the space community needs more organized approaches to positive artistic engagement with missions and science. We need more than science-communication TikToks, though they too have value, and we need to expand involvement across multiple disciplines and not rely as heavily on the visual artists as has traditionally been the case.

| For relatively little effort, NASA and other agencies (and even companies) could see a range of long-lasting, public-facing artwork that will humanize space exploration and valorize something that both art and science share: curiosity and a sense of wonder. |

So, I’d like to argue for the benefits of including wide artistic participation—poetry, music, visual arts, dance ,and more—as part of every mission’s public outreach. My vision is one in which every NASA mission (and ESA and JAXA and more) has an arts laureate who writes poetry or composes songs or paints watercolors or performs music as part of the public engagement process. This need not be expensive nor time-consuming—poets, for example, are used to being underpaid. (I know, I am one.) But for minimal investments mission laureates would create lasting and inspiring art works that are more than value-added: they will speak to the human passion for creation, whether of villanelles or data. Science-driven, factual, lyrical work about space missions—crewed and robotic—should be integrated into each project’s public outreach. For relatively little effort, NASA and other agencies (and even companies) could see a range of long-lasting, public-facing artwork that will humanize space exploration and valorize something that both art and science share: curiosity and a sense of wonder.

Practical considerations

There is no overarching policy from NASA Headquarters regarding artist involvement at the center or mission level. This is left up to centers and mission principal investigators. There is no specific budgeting for artistic engagement within public outreach. Some low-cost NASA missions have no public outreach budget at all. I believe there is a strong need to engage both agency personnel, outside organizations, and individuals in a concerted effort to change this state of affairs.

Here are some considerations and steps:

- Set up an advisory committee to draft guidelines for mission laureates

- Address types of artists to be solicited

- How long are they involved and in what way, e.g. access to facilities and meetings?

- Range of stipends

- Liability concerns

- Copyright and credit: Who owns the work?

- How is the work shared and over what timeframe?

- What are some value-added activities to increase output visibility, such as lectures, interviews and the like

- Selection criteria

- Make up of artists’ selection committees with emphasis on diversity at the mission level

Conclusion

As William Bezouska puts it in his paper, “The world abounds with tangible examples of this spirit in the work that connects art and space, from cases as simple as launching art into orbit to cases as complex as integrating artistic processes into the development of new space technologies. Space organizations that seek to identify and foster these connections may find benefits across the spectrum of space activity while at the same time supporting one of the most fundamental human activities: creating art.”

I’d like to end with a clarion call for advice and help from you and those in your network. Please consider me a resource and ally both in this effort and in specific projects you may be working on. I would love to begin to form a set of alliances that could lead to an advisory committee for NASA on the concept of mission laureates—which is the first step toward making this vision a reality.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.