A new approach to flagship space telescopesby Jeff Foust

|

| The decision to pick a concept between LUVOIR and HabEx was driven by science and budgets: big enough to do meet key science objectives like characterizing exoplanets, but also small enough to fit into a reasonable cost and schedule. |

The committee itself kept quiet about its work, providing little specific guidance about when to expect the final report. At a meeting of NASA’s Astrophysics Advisory Committee in October, Paul Hertz, director of the agency’s astrophysics division, presented the results of an office pool from earlier in the year predicting when the report would be released. All but two thought the report would have already been released by the mid-October meeting of that committee; those two predicted it would be released the week of Thanksgiving.

Fortunately, they and the rest of the astrophysics community did not have to wait until last week’s holiday to get their hands on the report. The document, released November 4, provided astronomers with a long-awaited roadmap for not just the next decade but arguably through the middle of the century, endorsing a set of observatories that can peer back into the distant early universe and also look for habitable worlds close to home.

While the decadal survey makes a series of recommendations for smaller missions and ground-based telescopes, what gets the most attention is its recommendation for a large strategic, or flagship, space mission. That recommendation is just that—NASA isn’t bound to accept it—yet the agency has adopted the top-ranked flagship missions of previous decadals. That includes the one picked in the previous decadal in 2010, which became the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), renamed by NASA to the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope last year.

NASA, in preparation for Astro2020, commissioned detailed studies of four proposed flagship observatories, operating from far infrared to X-ray wavelengths (see “Selecting the next great space observatory”, The Space Review, January 21, 2019.) These studies offered detailed technical, scientific, and budgetary information for the concepts, which were effectively finalists for the being the next flagship mission—although the decadal survey was not under any obligation to pick one.

And, in the end, they didn’t pick one of the four. Instead, the recommended flagship mission was something of a compromise between two of the concepts. One, the Habitable Exoplanet Observatory, or HabEx, proposed a space telescope between 3.2 and 4 meters across optimized to search for potentially habitable exoplanets. The other, the Large Ultraviolet Optical Infrared Surveyor, or LUVOIR, proposed a large space telescope between 8 and 15 meters across for use in a wide range of astrophysics, from exoplanet studies to cosmology.

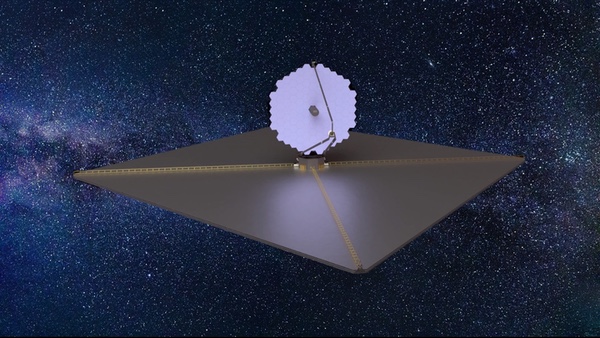

What the decadal recommended was a telescope six meters across capable of observations in ultraviolet, visible, and infrared wavelengths: similar to LUVOIR but scaled down to a size between the smaller version of LUVOIR and HabEx.

The decision to pick a concept between LUVOIR and HabEx was driven by science and budgets: big enough to do meet key science objectives like characterizing exoplanets, but also small enough to fit into a reasonable cost and schedule. “We thought that six meters provides assurance of enough target planets, but it’s also a big enough gain in capability over Hubble to really enable general astrophysics,” said Robert Kennicutt, an astronomer at the University of Arizona and Texas A&M University who was one of the two co-chairs of the decadal survey committee.

| “We realized that all of these are visionary ideas but they require timelines that are pan-decadal, even multi-generational,” said Harrison. “We really think a different approach needs to be taken.” |

That telescope—not given a name by the decadal survey—will still be expensive and take a long time to build. The decadal’s estimates, which included independent cost and schedule analyses, projected the telescope would cost $11 billion to build, in line with the James Webb Space Telescope when accounting for inflation, and be ready for launch in the first half of the 2040s. But the original LUVOIR concept would have cost $17 billion and not be ready until the 2050s, according to those same analyses. HabEx, the decadal survey concluded, would have been cheaper but too small to meet many of those science goals.

That selection of a flagship mission was, alone, not that different than past decadal surveys. Even that compromise pick is not unprecedented, as the previous decadal’s recommendation of what would become Roman emerged from combining several concepts. What was different, though, was the realization that, after the delays and cost overruns suffered by past flagships, notably the James Webb Space Telescope, NASA needed a different approach to developing such missions.

“We realized that all of these are visionary ideas but they require timelines that are pan-decadal, even multi-generational,” said Fiona Harrison of Caltech, the other co-chair of the steering committee, referring to the four flagship concepts studied for the decadal. “We really think a different approach needs to be taken.”

What the decadal survey recommended was that the space telescope it recommended be just the first mission to emerge from a new Great Observatories Mission and Technology Maturation Program at NASA. That program would mature technologies for a series of flagship missions in a coherent fashion.

“The survey committee expects that this process will result in decreased cost and risk and enable more frequent launches of flagship missions, even if it does require significantly more upfront investment prior to a decadal recommendation regarding implementation,” the committee concluded in the report.

Specifically, it recommended that, five years after starting work on the large space telescope that was the report’s top priority, NASA begin studies of two other flagship missions, a far infrared space telescope and an X-ray observatory, at estimated costs of $3–5 billion each. Both are similar to the other two flagship mission concepts studied by NASA for this decadal survey, the Origins Space Telescope and Lynx X-ray Observatory.

Setting up studies of those future mission concepts, without committing to them, allows NASA to adapt if both technologies or science goals change, another member of the decadal survey steering committee noted. “If the progress appears to be stalled or delayed, then we can rapidly onramp another one of the compelling, exciting ideas,” said Keivan Stassun of Vanderbilt University. “We can be phasing in multiple great ideas.”

| “We were tasked and encouraged by the funding agencies, including NASA, to really think big, bold, ambitious, and long-term,” Stassun said. |

The idea that it takes a long time to develop flagship space telescopes is not new: the first studies of JWST, originally called the Next Generation Space Telescope, predate the launch of the Hubble Space Telescope more than three decades ago, and that spacecraft is only now about to launch. But the study’s proposal recognizes that the problems experienced by JWST and, to a lesser extent, Roman, require a different approach to managing such complex, expensive missions.

It also reflects the realization that some of the questions that astrophysics is seeking to answer can’t be easily fit into decade-long timeframes. “We were tasked and encouraged by the funding agencies, including NASA, to really think big, bold, ambitious, and long-term,” Stassun said. “We took that to mean that we should not be thinking only about that which can be accomplished in a ten-year period.”

NASA’s Hertz had, in fact, urged the decadal survey to be bold on many occasions before and during its deliberations. “I asked the decadal survey to be ambitious, and I believe they are certainly ambitious,” he said at a November 8 meeting of the Committee on Astronomy and Astrophysics of the National Academies’ Space Studies Board.

NASA is only starting to review the overall recommendations of the decadal, he said. That includes not just its analysis of flagship missions but endorsement of a new medium-class line of “probe” missions, with a cost of $1.5 billion per mission and flying once a decade. Such missions would be analogous to the New Frontiers line of planetary science missions that fall between planetary science flagships and smaller Discovery class missions.

The delay in completing the decadal means it won’t have an impact on NASA’s next budget proposal for fiscal year 2023, which is already in active development for release in early 2022. Hertz said he’ll provide some initial comment on the decadal at a town hall meeting during the American Astronomical Society meeting in early January, particularly any recommendations that can be accommodated in the fiscal year 2022 budget. A complete, formal response will come later next year after a series of town hall meetings.

Those plans will depend on budgets. The first views Congress has on the decadal, including its flagship mission plans, will come Wednesday when the House Science Committee’s space subcommittee holds a hearing on the report.

Hertz was optimistic in general about the state of NASA’s astrophysics programs, citing the impending launch of JWST and Roman passing its critical design review. “I’m really excited. This is a great time for astrophysics,” he said. Astronomers hope the decadal’s recommendations, if implemented, can make it a great few decades for the field.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.