For JWST, the launch is only the beginning of the dramaby Jeff Foust

|

| “Of course, when you work on a $10 billion telescope, conservatism is the order of the day,” NASA’s Zurbuchen said after a launch processing incident last month. |

The launch of JWST has been for years largely an abstract concept: a long-term goal, but one many years away, and slipping to the right. The focus had been on the potential of the space telescope to revolutionize astronomy but also its development problems. The launch itself seemed like a distant dream.

That dream, though, is about to become reality, even with a few last-minute hiccups. Like a version of Zeno’s Paradox, as the launch date approach, the delays continued, but decreased from months and years to days.

A month ago, NASA announced that it was delayed the launch, then scheduled for December 18, by at least four days because of an incident during launch processing. A clamp band, used to secure the telescope to its launch adapter, released suddenly and unexpectedly, imparting vibrations to the spacecraft. Engineers needed more time to investigate the problem.

“Of course, when you work on a $10 billion telescope, conservatism is the order of the day,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said at the time. “It’s just the right thing to do right now, to do these tests, to make sure everything is as ready as we hope they are.”

A few days later, NASA confirmed that the tests showed no damage to the spacecraft, allowing launch preparations to continue with a revised launch date of December 22. That is, until last week, when what NASA described only as a “communication issue between the observatory and the launch vehicle system” caused the launch to slip again, this time to at least December 24.

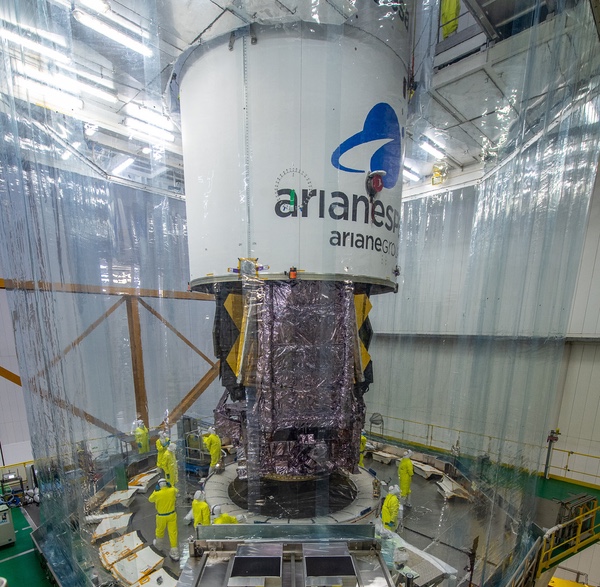

That issue, NASA and ESA officials later said, was with a cable connecting the telescope to ground equipment that was intermittently dropping data. That prevented engineers from conducting a final “aliveness test” of the spacecraft before enclosing it within the Ariane 5’s payload fairing.

Zurbuchen, in a press briefing last week scheduled before the communications issue was announced, described the problem as “finicky” to resolve. “Those of us in the launch business are aware of these occurring from time to time. It’s just, when it’s Webb, there are no small problems,” he said.

There were, in fact, two communications issues: the one with the cable delaying spacecraft testing, and one between the agencies involved and the public. The announcement of the problem and two-day delay offered no details about the problem. That announcement said a new launch date would be announced by Friday. However, by late Friday there was no announcement, only bits and pieces—a comment by NASA administrator Bill Nelson to an AP reporter, a tweet from a Space Telescope Science Institute scientist, an email to reporters who had signed up to cover the launch at the institute’s Baltimore headquarters—that the launch was on for the 24th. Official word from NASA and ESA didn’t come until Saturday.

| “I think of the sunshield deployment as something similar to a Rube Goldberg machine, in that it uses a series of reactions that work in succession, triggering one event after the other until the entire sunshield is fully deployed,” said Puga. |

Assuming no more minor issues in the days ahead, though, that Ariane 5 will lift off from Kourou Friday morning. For many, tensions are rising with the launch: after all, launches are dangerous, they argue, and the prospect of a failure turning $10 billion of hardware and decades of work into debris falling into the ocean fills astronomers’ hearts with dread. One meme making the rounds on social media contrasts a normal EKG with one wildly oscillating, representing the heartbeats of astronomers at the moment of liftoff.

But launch may be the least of their worries. JWST is launching on an Ariane 5, one of the most reliable of current major launch vehicles. Its last catastrophic failure was nearly 20 years ago (in 2018, an Ariane 5 launch left its payloads in the wrong orbits when the rocket’s guidance system was given incorrect coordinates; both GEO communications satellites were able to reach their desired orbits with some loss of mission lifetime.)

With JWST now cocooned inside its payload fairing, the final steps towards launch are much like a typical Ariane 5 launch. “From this moment onwards, it is more of a standard approach,” said Daniel Neuenschwander, ESA director of space transportation, at last week’s press briefing. “Of course, as Webb is a very special payload, we have further enhanced some aspects,” like additional oversight of the final steps towards launch.

The real drama will unfold—literally—in the hours, days, and weeks to follow. The launch of JWST marks only the beginning of the process of getting it to its final destination, the Earth-Sun L-2 Lagrange point 1.5 million kilometers away, and commissioning it for science. That requires a series of deployments, some never before attempted in space, to get the spacecraft into its final configuration.

Immediately after separation of JWST from the Ariane 5’s upper stage, a half-hour after liftoff, the spacecraft deploys its solar array to start generating power. That’s followed by a high-gain antenna two hours after launch. The first of three course-correction maneuvers takes place 12 hours after liftoff.

Over the next week, though, much bigger deployments follow. The spacecraft’s five-layer sunshield, folded up against the sides of the spacecraft at liftoff, begin deployment. NASA estimates it will take several days to extend and fully tension the sunshield, which has an area about the same as a tennis court.

“I think of the sunshield deployment as something similar to a Rube Goldberg machine, in that it uses a series of reactions that work in succession, triggering one event after the other until the entire sunshield is fully deployed,” said Krystal Puga, a spacecraft systems engineer for JWST at Northrop Grumman, the prime contractor for the mission. That system, she said at a briefing last month, includes 140 release mechanisms, 70 hinge assemblies, eight deployment motors, 400 pulleys, and 90 cables that are a combined 400 meters long.

All that complexity makes even veteran engineers nervous. Those release mechanisms, she said, all have to work perfectly for the sunshield to release. But, she added, years of testing has gone into that process. “This gives us the confidence that Webb is going to deploy successfully.”

| “When you’re talking about release mechanisms, mechanical release mechanisms, it’s usually pretty difficult to avoid an item we considered a single-point failure,” said Menzel. |

After the sunshield is deployed, engineers will turn to deploying the spacecraft’s segmented mirror. The tripod holding the secondary mirror deploys first, then two wide wings of primary mirror segments unfold into position. A month after launch, the fully deployed Webb should be entered its halo orbit around L-2.

There are still months of work ahead for JWST, though. The spacecraft’s mirrors and instruments will need to cool down, and the mirror segments aligned to within a fraction of a wavelength of infrared light. Webb’s main instruments will be calibrated and checked out, with science observations starting half a year after that liftoff.

There is no shortage of things that could go wrong for a mission where a lot of things have gone wrong in its development. At that briefing last month, Mike Menzel, lead mission systems engineer for JWST at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said there were 344 single-point failures on the spacecraft, 80% of which were associated with deployment mechanisms like the sunshield and telescope mirrors.

“When you have a release mechanism, it’s hard to put full redundancy into that,” he said. “When you’re talking about release mechanisms, mechanical release mechanisms, it’s usually pretty difficult to avoid an item we considered a single-point failure.”

The focus of that is on the sunshield. “The sunshield is one of those things that is almost inherently indeterministic,” he said. “The sunshield is one that has some risk to it.”

There are contingency scenarios, including steps engineers can take if deployments don’t go according to plan, said Alphonso Stewart, JWST deployment systems lead at Goddard. That includes a “shimmy” where the spacecraft is rocked back and forth and “fire and ice” to reorient the spacecraft with respect to the Sun to heat up some areas. That latter approach, he said, is something of a last-ditch effort if other steps fail. “Hopefully we don’t have to use that one.”

Engineers also have failure scenarios should, say, the sunshield not fully deploy. “I don’t think I would say that, if half of it didn’t deploy, we wouldn’t have a problem. We certainly would,” Menzel said. “If portions of it didn’t deploy exactly the way we wanted to, a lot of that would depend on where the misalignment was.” He added there were “cryogenic margins” in the design of the sunshield that could handle limited flaws in the sunshield’s deployment.

The risk of deployment problems, and the angst astronomers feel, is worth it given the potential of the telescope to revolutionize research in topics from the “cosmic dawn” of the universe to potentially habitable exoplanets to research within our own solar system. “Webb has this broad power to reveal the unexpected,” said Klaus Pontoppidan, JWST project scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute, during another briefing last month. “We can plan what we’re going to see, but at the end of the day we know that nature will surprise us more often than not.”

But, if you’re looking for a last-minute holiday gift for an astronomer, consider a bottle of antacid tablets. Maybe two, given what’s still to come after liftoff.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.