Blacker than a very black thing: the HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite signals intelligence payloadsby Dwayne Day

|

| New information indicates that the NRO, which operated the nation’s fleet of intelligence satellites, had a previously unknown program for collecting signals intelligence carried on the HEXAGON and perhaps other spacecraft. |

The rocket exploded only a few hundred feet above the ground, relatively close to the ocean, and rained pieces of rocket, propellant, and a top secret spy satellite all over the surrounding area. The satellite was a HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite, the last of its type, and its loss was a major blow to the American intelligence community, happening less than a year after another Titan launching from Vandenberg destroyed another reconnaissance satellite called CRYSTAL (originally KENNEN), leaving the United States with very limited reconnaissance capability.

In addition to the HEXAGON, there was another payload onboard, named LORRI II. Until now it was believed that LORRI II was a deployable subsatellite similar to dozens of others that had been pushed off various reconnaissance satellites for decades. But newly declassified information indicates that LORRI II was actually “an EHF search and VHF technical intelligence pallet” designed to stay attached to the HEXAGON in flight. And the new information indicates that the National Reconnaissance Office, which operated the nation’s fleet of intelligence satellites, had a previously unknown program for collecting signals intelligence carried on the HEXAGON and perhaps other spacecraft.

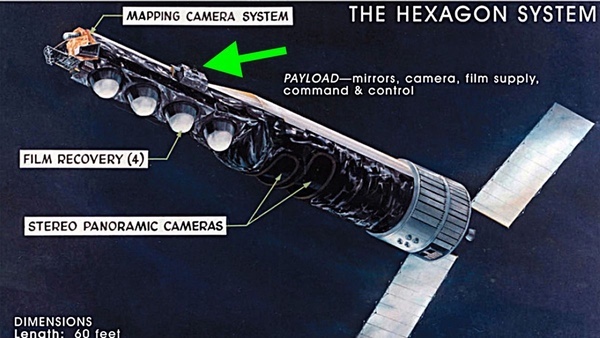

The last HEXAGON mission was launched in April 1986 and exploded above the pad. The HEXAGON reconnaissance satellite carried a signals intelligence payload called LORRI II attached to its side. (credit: US Air Force) |

AFTRACK

The first American reconnaissance satellites were named CORONA, and soon after they began flying in the late 1950s the Central Intelligence Agency began adding electronic boxes to the aft rack of the Agena spacecraft that carried them in orbit. The payloads often had deployable antennas that sprang out of the rear of the satellites and collected radar and other signals from over the Soviet Union. These were known as AFTRACK payloads and dozens of them were carried into orbit through the mid-1960s before the signals intelligence mission was transitioned to other spacecraft, although systems for detecting possible electronic attack and radar tracking of the satellites were continued into the 1970s. The AFTRACK program was replaced by signals intelligence payloads on small subsatellites that were deployed off the same Agena aft racks that had previously held attached electronics boxes. These subsatellites had their own individual names and mission numbers, and many of them were put in orbit in the latter 1960s before the program slowed its pace but continued to periodically launch satellites into the 1980s (see “Little Wizards: Signals intelligence satellites during the Cold War,” The Space Review, August 2, 2021.)

The AFTRACK payloads were given individual mission numbers to designate their intelligence mission. They were numbered starting with 7201 and so on, ending with 7225. According to a declassified letter from Secretary of the Air Force Edward “Pete” Aldridge a few days after the 1986 HEXAGON explosion, the LORRI II pallet was designated “Mission 7242” and was part of Program 989. Program 989 was a designation adopted in the mid-1960s covering signals intelligence subsatellites, but was not previously known to cover pallets that remained attached to satellites. The schoolbus-sized HEXAGON carried film in the mid-section of the spacecraft that fed into two powerful cameras forward. The exposed film then flowed forward into four large kettle-shaped reentry vehicles in the forebody of the spacecraft. The pallet would have been attached to the slab-sided forebody, an area that contained sufficient real estate for both attached payloads and deployable ones.

There all along

Although the revelation about LORRI II is new, the existence of these forebody pallets was essentially hiding in plain sight. The official history “The SIGINT Satellite Story” noted that the last of the Agena AFTRACK payloads, named SQUARE TWENTY, was launched in 1965 and had mission number 7225. It then stated that “although the 72XX series of mission numbers was continued after this time for secondary payloads, none were mounted on the aft rack during the time frame covered by this history.” The history went to 1975, implying that any additional 72XX missions flew after then.[1]

| Although the revelation about LORRI II is new, the existence of these forebody pallets was essentially hiding in plain sight. |

An official history of the HEXAGON program, “The HEXAGON Story,” noted that when HEXAGON was first designed it was planned that it “would carry subsatellites and critical space experiments into orbit to the extent that weight and volume permitted. Valuable space was allotted for the location of these ‘passengers’ on both sides of the forward section and in space under the protective shroud.”[2] It added that “a number of the later vehicles carried pallet-borne and other experiments (which remained with the SV), in lieu of a subsatellite. Some of these experiments were warning devices designed to detect radar or laser illumination of the HEXAGON satellite.”[3] Confusingly, “The HEXAGON Story” states that the last HEXAGON carried a subsatellite, but the newly-declassified information does not refer to a satellite, only a “pallet.”

The new information also indicates that LORRI II was part of Program 989, the designation that had been applied to small signals intelligence satellites starting in the 1960s. Some of those satellites were launched in the 1980s, so clearly the satellites and the pallets were covered by the same program number and managed by the same office at the NRO’s West Coast organization, known as the Secretary of the Air Force Special Projects office, or SAFSP.

The sleuths were onto something

Satellite observers should have realized that something was not quite right with the information we already had about LORRI II. Although the name LORRI II had been public for several years, there was no available information about a LORRI I payload. If there was a LORRI I pallet, it undoubtedly flew on an earlier HEXAGON satellite, and mission numbers 7226 up to 7242 remain unaccounted for. There were 19 HEXAGON missions launched between 1971 and 1984, so those 16 mission numbers were spread among them.

| That last HEXAGON mission—designated mission 1220—involved a very special Christmas tree of a spacecraft. Because it was the last, and because HEXAGON had payload capability to spare, it was loaded up with extra payloads. |

But it turns out that various observers of satellite programs had suspected that the large HEXAGON—then known by the nickname “the Big Bird”—carried other payloads. Reginald Turnill, in his 1974 book The Observer's Book of Unmanned Spaceflight, wrote: "Big Bird is almost certainly capable of carrying out some Elint [electronic intelligence]… as well, and sometimes carries with it a small 132-lb piggy-back capsule, placed in a higher orbit for such operations…” Paul Stares, in his 1987 book Space and National Security, wrote “it is also likely that US photoreconnaissance satellites possess equipment for gathering electronic intelligence.” Reagan-era DARPA director Robert Cooper was quoted in Stares’ book as saying, “typically our spacecraft look much like Christmas trees. They have a number of different missions attached to any given space platform…”

That last HEXAGON mission—designated mission 1220—involved a very special Christmas tree of a spacecraft. Because it was the last, and because HEXAGON had payload capability to spare, it was loaded up with extra payloads. It contained a special infrared camera called the S3 or “S-cubed,” that looked down and could have been used to detect camouflaged objects. The NRO’s plan was to operate the spacecraft even after its film was used up and its reentry vehicles brought back to Earth. S-cubed did not require film, and the LORRI II payload would have had no consumables and would have run as long as the satellite provided power (see “Above Top Secret: the last flight of the Big Bird,” The Space Review, February 18, 2019.)

Now that the NRO has released this new information on the HEXAGON capabilities, we will hopefully soon learn more about their other missions.

List of HEXAGON missions

Twenty HEXAGON satellites were launched between 1971 and 1986. Many of them carried deployable satellites and attached signals intelligence payloads. It is unclear what payloads were attached to specific missions.

| Mission 1201 | June 15, 1971 |

| Mission 1202 | January 20 1972 |

| Mission 1203 | July 7, 1972 |

| Mission 1204 | October 10, 1972 |

| Mission 1205 | March 9, 1973 |

| Mission 1206 | July 13, 1973 |

| Mission 1207 | November 10, 1973 |

| Mission 1208 | April 10, 1974 |

| Mission 1209 | October 29, 1974 |

| Mission 1210 | June 8, 1975 |

| Mission 1211 | December 4, 1975 |

| Mission 1212 | July 8, 1976 |

| Mission 1213 | June 27, 1977 |

| Mission 1214 | March 16, 1978 |

| Mission 1215 | March 16, 1979 |

| Mission 1216 | June 18, 1980 |

| Mission 1217 | May, 11, 1982 |

| Mission 1218 | June 20, 1983 |

| Mission 1219 | June 25, 1984 |

| Mission 1220 | April 18, 1986 |

Endnotes

- Major General David D. Bradburn, U.S. Air Force; Colonel John O. Copley, U.S. Air Force; Raymond B. Potts, National Security Agency; [deleted name], National Security Agency, “The SIGINT Satellite Story,” National Reconnaissance Office, 1994, p. 123.

- Frederick C.E. Oder, James C. Fitzpatrick, and Paul E. Worthman, “The HEXAGON Story,” NRO, 1992, p. 116.

- “The HEXAGON Story,” p. 119.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.