Cold War Pony Express in the western Pacificby Mike Beuster

|

| I came to work one day and noticed a silhouette of a ship next to my name on the work status board. I said, “What’s this?!” |

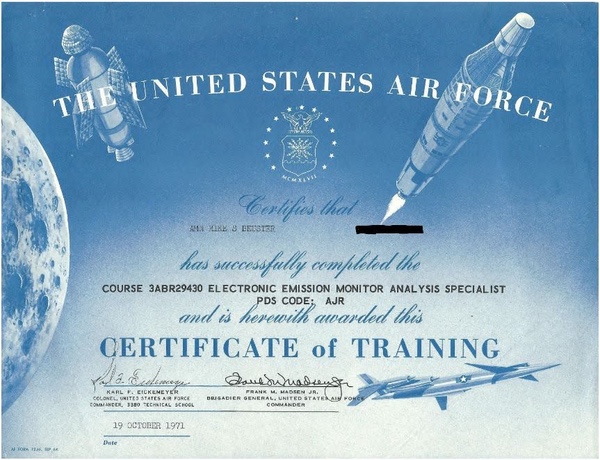

In the spring of 1974, after leaving Shemya Island, Alaska, where I had been assigned to the ANDERS signals intelligence listening facility, I had requested re-assignment back to Fort Meade to the USAFSS 6970th Air Base Group. But I was unaware that another unit was also supporting NSA from Fort Meade, I was assigned to OL EB, 6948 Security Squadron (Mobile), Fort Meade, Maryland. Thinking nothing of the change in my orders, I was biding my time as a telemetry signals analyst in the National Security Agency’s W17 group.

I came to work one day and noticed a silhouette of a ship next to my name on the work status board. I said, “What’s this?!” They said, “You’re going on Project Pony Express; here’s your orders.” I said, “But I’m supposed to get out in January 1975.” The ship was the USNS Arnold, not the ground stations I was used too, and I would be out at sea. I was told not to worry, that I could get off the ARNOLD in Japan before the second part of the trip.

The orders were for 90 days, and later they were amended/extended to 170+ days, which was past my January 1975 separation date. (Could they do that? Yes!) I went to the Arnold in August 1974. The trip to Oakland, California from Fort Meade, Maryland is a blur. I stopped by San Diego to say goodbye to the family. My dad was a 22-year World War II Navy veteran and had told me before enlisting, “Don’t go into the Navy, you will spend all your time at sea.”

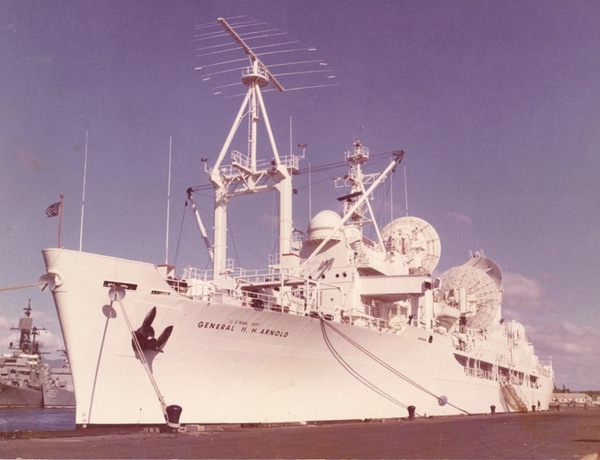

Although designed as a “missile range instrumentation ship,” in the 1960s the Arnold had been put into additional service monitoring Soviet missile tests. I was part of a USAFSS special team on board the Arnold that performed Soviet ICBM telemetry and electronic intelligence (telemetry and radar) collection.

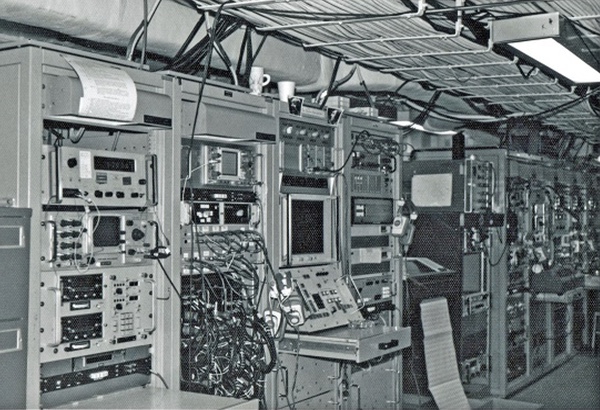

TEL 1 location on the ship. GTE-Sylvania special receivers computer/printer. My position right of printer. Watkins Johson VHF/UHF receiver and panoramic scope. (courtesy of the author) |

Others aboard the Arnold on the Pony Express cruise included Air Force Security Service and Naval Security Group linguists, civilian receiver/computer technicians from ESL, Inc., and GTE/Sylvania and civilian RCA Arnold instrumentation missile tracking radars and optical trackers technicians/operators.

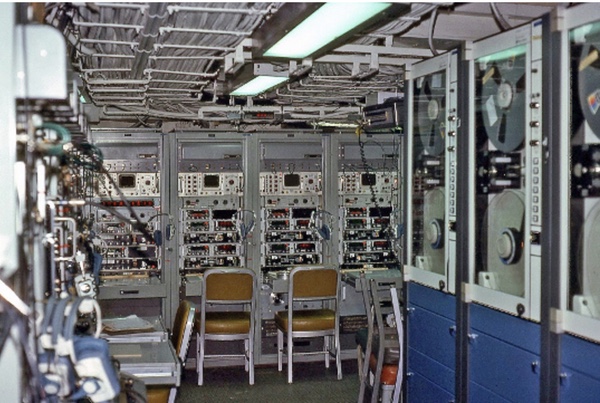

Tel 2 position on the ship. Watkins Johnson receivers UHF/VHF, HP spectrum analyzers, and Bell and Howell VR3700 Datatape14 track recorders. (courtesy of the author) |

In late August/early September, we left Oakland, California, after a refueling probe and plumbing to the fuel tanks was welded on to the ship (a first time for this ship, which had not been equipped for refueling at sea.) This allowed the Arnold to remain at sea for another 30 days after a refuel at sea (I should have known, just my luck.) In addition, a VHF spiral helix antenna from ESL Inc. was added to the port side.

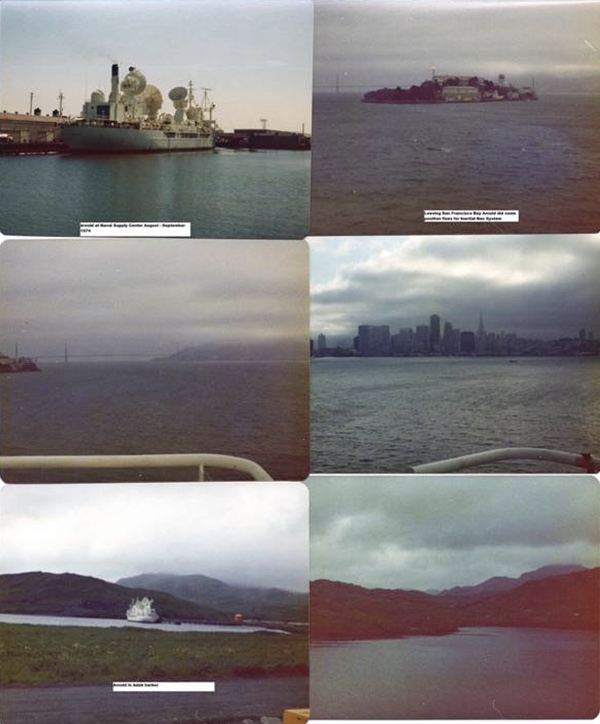

Arnold in the Port of Oakland, then leaving through San Francisco Bay. We arrived in Adak Harbor about three days later. (courtesy of the author) |

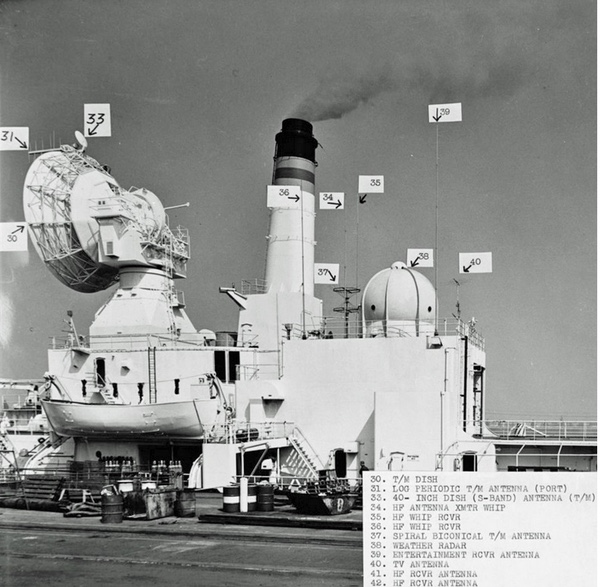

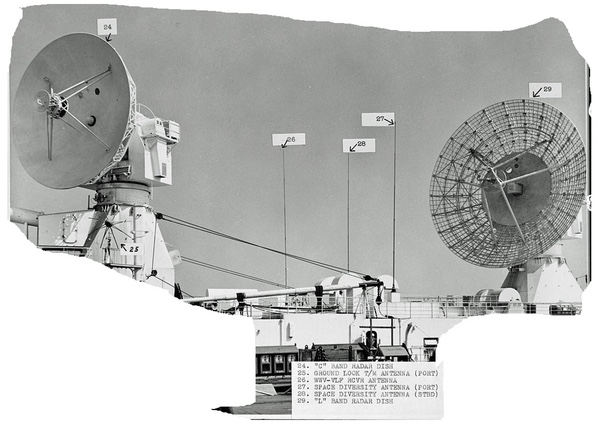

Now heading for Adak, Alaska, it was smooth leaving San Francisco Bay past Alcatraz but a rough three-day trip just past the Golden Gate in a former World War II troop-carrier ship now carrying a top-heavy 60-foot (18-meter) L-Band/UHF multi-megawatt tracking radar. That was right next to our 45-foot (14-meter) telemetry dish and another 30-foot (nine-meter) C-Band radar dish at the other end, making it very top heavy. We were told the ship would completely roll over past a 30-degree list. The ship also carried several optical trackers run by RCA.

The Arnold’s 40-foot telemetry dish. (courtesy of the author) |

After almost three solid days of my being seasick (up wave 4 knots, down wave 10 knots, up and down, up and down), we finally made it to Adak.

The Arnold’s 35-foot C-Band radar dish and 60-foot L-band/UHF dish. The Arnold’s many dishes made the ship top-heavy and she rolled in rough seas. (courtesy of the author) |

For some reason the senior RCA tech waited until I was finally feeling better and was standing by the railing getting some fresh salt air to come by me and light up a big green cigar and ask, “Mike, how ya feeling?” Green again!

We refueled and resupplied at Adak Harbor. Adak, Alaska, was civilization compared to Shemya. The Navy base even had liquor (I thought I heard bottles in paper bags clanking when the RCA techs came up the gangplank.) We then headed out past Shemya, my previous posting. I waved but no one waved back—must have been dark. Now off to Kamchatka, Siberia.

Arnold’s tech lounge/game room. (courtesy of the author) |

On the way to the operating area, we found a ping-pong table in a room almost at the bow. We found that, as the ship crested, a large wave we could get a couple of feet off the deck with some great “hang time” and then smashing the ball back—very hard to hit back before landing back on the wave surface other side.

Our operating area was 25 miles (40 kilometers) off the coast, monitoring the Klyuchi Impact Range.

We started our mission, going around and around in a racetrack pattern. A KGB tug and gunboat came out, and they didn’t look too pleased that we were there. We waved. I took the tugboat picture with my Kodak Instamatic. They didn’t wave back or smile. That’s okay: if they wanted trouble we had our Geneva Convention Cards with us, but no uniforms though (remember the Pueblo and the Liberty?)

KGB tugboat. They kept a close eye on us. (courtesy of the author) |

We spent quite a bit of time on station, then had to leave due to bad weather: 40-foot (12-meter) seas, 50 mph (80 km/h) winds. The spiral helix broke loose. I helped the ESL tech tie it down above the balloon deck during an ice storm. The ship’s captain took the ship behind the Commander Islands, Komandorski Islands, (or Komandorskie Islands) for refuge from the storm from Siberia.

ESL spiral helix antenna. (courtesy of the author) |

We went back to Adak to drop off a sick civilian seaman. This diversion caused us to miss an alert. Our customer was not happy.

In October 1974, instead of heading back to Siberia, we were sent to the Broad Ocean Area (BOA) between Midway and Hawaii to support expected upcoming Soviet long-range ICBM activities.

We expected Soviet long-range ICBM activities. That is why we were there. We were out in the ocean long enough to be refueled/re-supplied. This was a first refueling at sea for the Arnold by the USS Sacramento, which was on her way to Japan. (courtesy of the author) |

We were refueled and re-supplied by the USS Sacramento on her way to Japan. The Arnold captain was very nervous having to get so close to the Sacramento while re-fueling. We decided to go up to the deck above the flying bridge where the ship’s captain was because the ESL rep wanted to play his tape cassette of Hank Snow’s “Beyond The Reef”:

Beyond the reef where the sea is dark and cold

My love has gone and my dreams grow old

There’ll be no tears there’ll be no regretting will she remember me will she forget

I’ll send a thousand flowers where the trade winds blow…

I guess the captain didn’t like the song and we had to go below. Kind of reminded me of the movie Mr. Roberts or Captain Queeg in The Caine Mutiny.

After that we started to go the bow every evening after dinner and played the tape while watch for the “green flash,” an optical phenomenon that you can see shortly after sunset or before sunrise. It happens when the sun is almost entirely below the horizon, with the barest edge of the sun—the upper edge—still visible If you don’t go blind first watching the sunset.

Green flash seen as the sun goes down. One of our distractions during our long sea duty. (courtesy of the author) |

The Sacramento came back 30 days later and we were still there going around and around. They were surprised we were still in the same area, as Navy ships at the time didn’t stay in one area for 30 days and not pull into port. Since they gave us movies on the way by during the refuel, they wouldn’t swap movies with us now as they had already seen the ones they had given to us 30 days earlier.

We had very little alert activity. We only went to the Special Operations Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility space (SKIF, pronounced “skiff”), a US Department of Defense term for a secure room to man the Telemetry 1 (TEL1) and Telemetry 2 (TEL2) collection equipment positions when on alert (maybe two or three times) for a few hours until the actual event or termination.

We played many hours of double deck pinochle and acey-deucey (also spelled “acey-deucy” or “acey-ducey”), one of the most popular backgammon variants. A lot of the RCA techs played dominos. We were warned to stay away from the ship’s merchant marine crew or we might find ourselves overboard.

| We started our mission, going around and around in a racetrack pattern. A KGB tug and gunboat came out, and they didn’t look too pleased that we were there. We waved. |

Finally, after wandering around in the middle of the ocean for weeks, we got some activity: indication of a Soviet missile launch. I had the ELINT tip-off position, which alerted the other positions to start searching for telemetry on the manual receivers, and to watch for lock on the ESL automatic receivers. GTE did their own thing with their computer-controlled receivers.

My job turned out to be difficult because of the high-power UHF/L-band radar next to our telemetry dish antenna. That was because what I was looking for on the pan scope was almost washed out by RCA operators switching to various pulse repetition frequencies (PRF) on the L-Band/UHF radar to get better resolution of the reentry vehicles.

Around this event a Navy linguist reported that a Russian helicopter was being sent over to our ship. The Navy linguist threw down his headset and ran out of the SCIF. We USAFSS wondered what he was doing. When he came back, he was all smiles as he was able to make it up to the deck above the flying bridge and was able to moon the Russian taking pictures from the helicopter.

Our work at sea made it into the news. According to an October 3, 1974, Associated Press report, “The Russians have test‐fired two new long-range submarine‐launched missiles about 4,900 miles from the Barents Sea into the Pacific, the Pentagon announced today. The Pentagon said the two SS‐8 submarine‐launched missiles were single warheads. They landed about 500 nautical miles north of Midway Island, the Pentagon said.”

During the Broad Ocean Area activity, we watched the Soviets on their own tracking ships (Chazma, Chumikan, Chukotka, Spassk) in the area. They had a swimming pool and volleyball. We had a balloon deck in the stern (the round back end of the ship) where I set up my beach chair to sun myself. I initially set it up underneath the 60-foot dish—a bad idea when the RCA techs decided to do a radar calibration and took it out of the stowage position. I quickly moved to the balloon deck.

Arnold’s balloon deck/sun deck. (courtesy of the author) |

We had a couple of Navy destroyer escorts (DE), USS Charles Berry and USS McMorris, with us in the BOA. Both had round hulls and were always rolling no matter how smooth the ocean.

A US Navy P-3 Orion aircraft was usually flying around and once dropped some sonar buoys around the Arnold as a sub was believed to be under us. I went to the Ops area and was able to pick up the sonar buoys signal in VHF. It was just some underwater gurgling sounds since we didn’t have the necessary processing equipment.

| The Navy chief asked me, “How long have you been on the ship?” I told him, “Going on two months.” He said, “Mike, you have more sea duty time than I do, and I have been in the Navy for 13 years, all shore duty.” |

In November 1974, we finally left the BOA and headed to Yokosuka, Japan, for resupply. A day before we were to arrive, we received a message saying that most of us were extended for the duration of the second trip. They pulled the plug on the communications center right after that which prevented any communications back to headquarters. Shanghaied!

Regret that all OL EB personnel cannot be replaced. Severe budgetary restrictions and lack of qualified replacements are the reasons. Individuals remaining for entire trip should not participate in first trip next year. All leave requests are approved. Amendments will be prepared and be available upon your return [replenishing stop at Yokosuka].

We pulled into Yokosuka for repairs where ESL tech workers added another spiral helix on the starboard side of the ship.

We took a trip to Tokyo, a beautiful city, It was the Emperor’s birthday and quiet around the palace area. We also went to the Chiefs Club on base. They couldn’t believe we had been out more than 30 days and not been to port.

We were re-supplied with steak and lobster—a GTE/Sylvania rep had complained to the Fort (Fort Meade, NSA headquarters) about the food on the first part of the trip. I thought the food was okay but was even better on the second part of the trip. It might have been because of the senior government officials who came on board for the second phase of the trip. One of them was an expert on multiple independent re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) and gave a very interesting briefing.

We initially headed back north, but the ship was diverted again to the BOA in the mid-Pacific for more Soviet activity.

We had an Air Force major on board, and he decided that instead of waiting around for tip offs of possible launches he thought we should go to our positions and practice “tuning the receivers across the frequency bands.” Daily? We had a Navy Security Group chief who was the special team lead on the second part of the trip. He had a big red beard and told the Air Force major that it was a “bad idea,” in so many words.

The Navy chief asked me, “How long have you been on the ship?” I told him, “Going on two months.” He said, “Mike, you have more sea duty time than I do, and I have been in the Navy for 13 years, all shore duty.” Then he said, “and my next assignment after this will be SUGARGROVE West ‘By God’ Virginia,” followed by a big laugh!

Note: USAF sea duty pay was $13 a month, and my DD214 after separation didn’t show the sea duty of this trip. Civilian techs were getting $1,000 a week just for being at sea. They never wanted to go to port.

Arnold at Pearl Harbor. She was not a pretty ship. (courtesy of the author) |

This time, instead of meeting up with the Sacramento, we had to go to Pearl Harbor for resupply. A bunch of NAVSECGRU communications technicians (CTs) off our destroyer escorts were waiting pier side to volunteer to go out, as the USNS Arnold had much better accommodations and a relatively smoother ride in smooth seas than their tiny tin cans. The USAFSS said no to the Navy CTs: it’s an Air Force show.

I was able to convince the Fort Meade government Pacific rep that they had enough Electronic Intelligence Operators (R205X0’s, was R294X0s) on board and that I needed to get back to Fort Meade for my separation. A USAF colonel saw me in the hallway with long hair and civilian clothes and said, “Are you off the Arnold?” I said, “yes.” Then he asked, “What AFSC skill code?” I said 205. He said, “I just did a study of you guys and there are only 500 of you in the entire USAFSS.” I said wrong… 499, I’m getting out. There were only a couple of overseas assignments for us at the time. Either Sinop, Turkey, or Shemya, Alaska. I didn’t want to go to Survival School and then to Offutt, Nebraska for RC-135 Rivet Joint Airborne 13-hour missions.

Arnold Special Team in fall 1974. The author is under the red arrow. (courtesy of the author) |

I was discharged on schedule at the end of my four-year Air Force enlistment in January 1975. I immediately hired on with a DoD contractor and spent the next 30 years supporting classified ground and space related signal/other collection and processing programs.

|

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.