A phoenix dying in Samos ashes: The SPARTAN reconnaissance satellite programby Dwayne Day

|

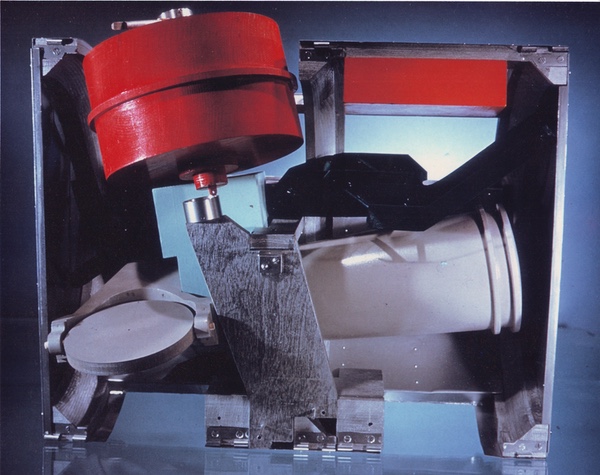

A wooden model of the Samos E-6 camera made by Eastman-Kodak. The red drum contained the film-supply for the two cameras. There are no good photos of the actual camera system. The E-6 used a mirror looking out an aperture. (credit: NRO) |

The early years

The United States’ first effort to develop a reconnaissance satellite was named Weapons System 117L. It began in 1956 and, around the time of Sputnik, split into several projects, including the Sentry reconnaissance program. Sentry was soon renamed Samos—which, contrary to some claims, was not an acronym for “satellite and missile observation system”—and Samos itself soon evolved into multiple programs. The Samos program was run by the Secretary of the Air Force Special Projects office, usually referred to either as SAFSP or, more commonly, “special projects.” Located in Los Angeles, SAFSP was part of the relatively new National Reconnaissance Office, a loose conglomeration of government agencies cooperating—more or less—on developing satellite reconnaissance systems. SAFSP cooperated with the Central Intelligence Agency on an offshoot program known as CORONA that returned its film to Earth in kettle-shaped reentry vehicles, achieving first success in August 1960.

| The operation of the E-6 camera remains a bit of a mystery to this day. |

One of the persistent misconceptions about Samos is that it was a film-readout system intended to develop film in orbit, scan it, and beam the images back to a ground station. The early Samos projects, known as E-1 and E-2, involved this technology. But Samos soon evolved to include the E-4 mapping system, the E-5 higher-resolution system, and the E-6 search system, all of which were designed to return their film to Earth inside reentry vehicles. Although E-4 was canceled before it ever took flight (E-3 never left the study phase), the Air Force launched both Samos E-5 and E-6 satellites starting in the early 1960s. But their reentry vehicles suffered problems and in early 1962 the E-5 program was canceled.

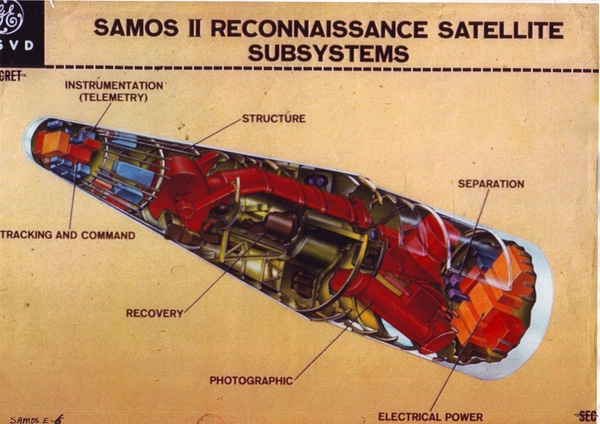

The Samos E-6 incorporated two 36-inch (0.91-meter) focal length Eastman-Kodak manufactured cameras that could scan large areas of the ground below at an estimated resolution of about six and a half feet (1.98 meters), good enough to spot and identify aircraft, ships, submarines, and possibly even military ground vehicles, and better than the early CORONA versions. (CORONA had a 24-inch/0.60-meter focal length.) After the film was exposed in the cameras it was wound up on spools inside the reentry vehicle.

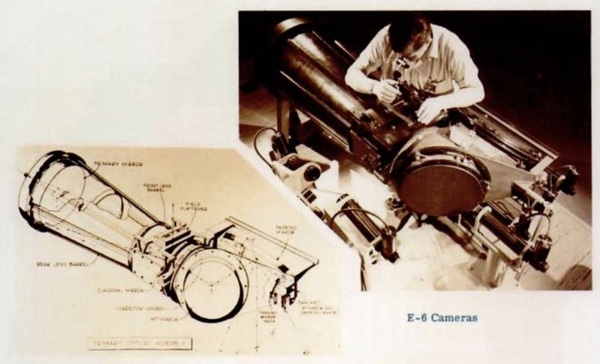

The operation of the E-6 camera remains a bit of a mystery to this day. It consisted of a long tube with an image-reflecting mirror at one end that bent the image of the Earth below 90 degrees and sent it down the tube with an image-focusing mirror at the other end. That focusing mirror concentrated the image and sent it about halfway back the tube where another small mirror reflected it up and onto a film strip that was pulled across an aperture. The focal length was 0.7 meters, compared to CORONA’s 0.61-meter focal length. Only one, poorly reproduced image of the camera design exists, along with some photographs of a wooden camera mockup, and it is unclear how the camera scanned the ground below from side to side. Other specific operational details remain unknown. Carrying two cameras meant that one could point at a slightly different angle than the other one, so that they imaged the ground at different viewing angles, which made measurement of objects on the ground easier.

Artist impression of the Samos E-6 spacecraft that was launched five times in 1962, but failed each time due to problems with the reentry vehicle. The spacecraft had two panoramic cameras and sent the exposed film to a long, thin reentry vehicle. The SPARTAN program would have used a single camera and a CORONA reentry vehicle. (credit: NRO) |

Reentry problems

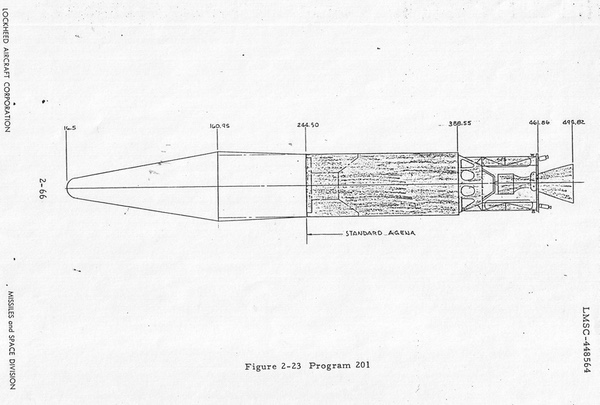

The Samos E-5 reentry vehicle was large, nearly the size of a Mercury spacecraft, and also would have returned the camera to Earth. In contrast, the Samos E-6 reentry vehicle was long and pointed, and would not have returned the cameras, only the exposed film. While hanging underneath a parachute it would have been grabbed out of the air by an Air Force C-130 transport plane in a method that CORONA had successfully demonstrated numerous times. If the plane missed, the E-6 reentry vehicle would sink in the ocean, whereas the CORONA vehicle floated for a limited time before it eventually sank to prevent recovery by the Soviet Navy.

The Air Force launched Atlas Agena rockets with Samos E-6 satellites in April, June, July, August, and November 1962. All failed to successfully return film. The E-6 reentry vehicle overheated and was destroyed before it could ever deploy its parachute. The multiple failures led to serious doubts about the program within the Air Force and intelligence community.

On December 11, 1962, Air Force Undersecretary Joseph Charyk, who was also Director of the National Reconnaissance Office, terminated the Samos E-6 program and ordered that the remaining cameras and payload vehicles be placed into storage.[1]

Charyk’s decision was not only based on the E-6’s reentry vehicle problems but on several other factors. The E-6 required an expensive Atlas Agena launch vehicle. There was also a perception among some of those who knew of the program that it was of dubious value. Finally, the latest version of CORONA, known as the CORONA-MURAL as well as the KH-4, accomplished many of the same goals as the E-6, using proven equipment and a less expensive Thor Agena launch vehicle.

Line drawing showing the overall shape of the Samos E-6 satellite. The original cover story for the program was that it was linked to an orbital nuclear weapons program. This was a bizarre choice for a cover story, because it was more alarming than the actual spacecraft mission. (credit: USAF Report) |

Phoenix from ashes

At the time he canceled the E-6, Charyk also ordered that SAFSP investigate the possibility of launching a single E-6 camera into orbit. He gave Major General Robert E. Greer, who ran SAFSP, discretion in finishing out the E-6 program and determining what could be done to salvage the work performed to date. Charyk’s idea was that the goal would be to prove the capability of the E-6 camera in orbit rather than to develop a new area search system to replace CORONA.

| The E-6 required an expensive Atlas Agena launch vehicle. There was also a perception among some of those who knew of the program that it was of dubious value. |

Charyk’s suggestion to adapt a Samos camera to proven CORONA technology was not unprecedented. After it became apparent that the Samos E-5 was having major problems, in late 1961 Charyk had agreed—with CIA support—to use the camera in combination with CORONA equipment in a new satellite reconnaissance program named LANYARD. LANYARD development was underway throughout 1962 with a planned launch in the first half of 1963. LANYARD was an effort to obtain better resolution photography than CORONA in the near-term, before a higher-resolution satellite known as GAMBIT entered service in mid-1963. Charyk was trying to do something similar to what was already being tried with LANYARD, what one CIA official referred to as “making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.” The key difference was that LANYARD was supposed to be an operational system to gather intelligence, whereas Charyk’s proposal for E-6 was for an experimental system.

The Samos program office quickly responded with three options. The first was to keep the Atlas Agena, develop a satellite midsection adapter to hold a single E-6 camera, and use a CORONA reentry vehicle. An additional option was to continue testing the E-6 reentry vehicle by mounting it to an Atlas rocket and lofting it on a trajectory that would test its heating qualities. The final option was to use the planned Thrust Augmented Thor (TAT) Agena rocket, a new midsection atop the Agena with a single E-6 camera, and a CORONA reentry vehicle. The satellite would make one pass over the Soviet Union taking photos and then be recovered on the second pass, at nighttime over the Pacific Ocean, providing “invulnerable reconnaissance” of the Soviet Union. The Atlas Agena option could possibly be ready as early as April 1963, with the cheaper TAT-Agena vehicle available by November. Another option involved carrying both E-6 cameras on an Atlas Agena equipped with two CORONA reentry vehicles. A final option consisted of converting the camera to handle narrower film, which would enable two E-6 cameras to use a single CORONA reentry vehicle.

SAFSP’s recommended version was for a single camera and the Atlas Agena rocket using a CORONA reentry vehicle, along with the Atlas test of the original E-6 reentry vehicle. SAFSP also recommended development of a lighter weight midsection to hold the single camera. In addition, the special projects office noted that it was possible to merge the E-6 camera with Samos E-1 and E-2 hardware to create a “recovery-readout” capability. At the time, five E-1 and three E-2 camera payloads were still in storage and the ground equipment also still existed. There were eight E-6 cameras in storage.

The only image of the E-6 camera's internal makeup, and the only image of an actual E-6 camera. The camera scanned the ground below, covering a significant area on each photographic pass. A single camera would have been used for the SPARTAN program. The author is interested in hearing from anybody who understands how this panoramic camera actually worked. (credit: USAF) |

SPARTAN is born

After some delays, at the end of January 1963, Charyk approved a “black,” or covert, project to demonstrate the E-6 camera in orbit. The work on the new project would not be done in the SAFSP offices in Los Angeles but in a nearby Eastman-Kodak facility. Charyk ordered that they use the TAT-Agena option with a CORONA reentry vehicle. But there remained many details to be decided, including whether to use an Agena B or the more capable Agena D upper stage. Other decisions concerned developing a new satellite midsection, identifying a funding channel and cover plan, and determining how to procure CORONA reentry vehicles without disclosing the new covert project’s existence.[2] A day after approving the covert program, Charyk ordered that no more Samos E-6 missions be conducted.

Charyk’s approval stated that “The approach should be spartan in nature, as simple as possible, and should take no consideration of any future system applications.” That order resulted in the project being named SPARTAN, although on February 2 it also received the formal designation of Special Project-Advanced Study 1963, or SP-AS-63.[3]

| Despite Charyk’s approval, SPARTAN ended up in a strange state of limbo throughout February, apparently due to CIA opposition. |

Once it was approved, the concept evolved into two possible design approaches. The first would have a single camera, the original E-6 midsection, and a single CORONA type reentry vehicle. The second approach was to have a single camera equipped with a mirror to provide stereo capability. It would require a redesigned midsection and either an enlarged reentry vehicle or two reentry vehicles in tandem to enable it to operate longer and take more photographs.[4]

Whereas the Samos E-6 was designed to operate in a 125-nautical mile (231-kilometer) orbit, SPARTAN would operate in a 100-nautical mile (185-kilometer) orbit. The single SPARTAN camera would also have improved lens-film definition, meaning that the images focused by its lenses would result in more detail on the film. If it worked as planned, SPARTAN would have better resolution than the Samos E-6.[5]

Despite Charyk’s approval, SPARTAN ended up in a strange state of limbo throughout February, apparently due to CIA opposition. Herbert Scoville, CIA’s deputy director for research and the official in charge of CIA reconnaissance satellites, perceived SPARTAN to be a competitor to the CIA’s plans to improve CORONA’s performance. Although SPARTAN was officially only an experiment, Scoville indicated that he suspected it was a prelude to a new satellite system. The CIA was then evaluating a proposed MURAL-2 (or M-2) concept that would have provided a resolution of six to eight feet (1.8 to 2.4 meters) resolution, compared to SPARTAN’s resolution of six to seven feet (1.8 to 2.1 meters) resolution. At the time, other issues had resulted in a deteriorating relationship between Scoville and Charyk, and Scoville was now questioning every decision Charyk made.

During this limbo period, work on SPARTAN continued on the West Coast. SAFSP developed a budget and a plan for launching four vehicles starting in July 1963. A cover story was produced that it was for development of a new reconnaissance system, although the specific details of that cover story remain classified. Kodak was actively working on plans to modify the camera for use in the new vehicle.

On February 12, Charyk disapproved the specific SPARTAN proposal, although he allowed the studies to continue. Charyk’s decision was apparently due to Scoville’s opposition to SPARTAN. But both Charyk and General Greer had doubts that the CIA’s M-2 camera could provide consistent quality, whereas they believed that the E-6 camera had a smoother operation that would be more reliable. Charyk engaged in a game of bureaucratic sleight-of-hand: SAFSP could continue studies of using the E-6 camera with the goal of achieving SPARTAN’s objectives, a distinction with very little difference. SAFSP was spending money to procure hardware, not simply conduct studies. On February 18, Eastman-Kodak received the contract for the SPARTAN camera modification work.[6]

By this time, Kodak had also determined that using a mirror with a single E-6 camera could provide stereo imagery with six-foot (1.8-meter) resolution, possible because new mirror coatings would improve the quality of the image going into the camera. The swath width would be 17 by 140 nautical miles (32 by 259 kilometers). Kodak also proposed that it construct the camera vehicle in-house rather than delegating that task to General Electric. In addition, Kodak suggested other camera modifications to improve performance.[7]

Charyk’s “disapproval” of the SPARTAN plan effectively ended the name as well, and after that point all work was referred to as SP-AS-63. Kodak proposed a minimally modified E-6 camera for the first flight by July, which it designated the Type A configuration. The company also planned to deliver four vehicles between July 21 and September 15. The Type B configuration would increase film capacity, improve resolution, and provide for stereo photography. General Electric would provide a scaled-up reentry vehicle that would be 45 inches (1.14 meters) in diameter compared to the original 33-inch (0.83-meter) diameter for the CORONA vehicle. Kodak also indicated that there were other growth options for the camera system that would improve performance and reliability.[8] Despite it being an experimental program, all parties involved were looking for as many improvements as possible.

By March, Joseph Charyk had left as NRO director to become head of the newly established Comsat Corporation, at a considerable salary increase. He was replaced as DNRO by Brockway McMillan, who inherited a rapidly deteriorating relationship with the CIA and lacked Charyk’s reputation. McMillan ordered a special study of an “improved search type satellite reconnaissance system” which would include variations of the Samos E-6 as well as the CIA’s M-2. Rather than reinforcing the work that was already underway, McMillan’s study had the effect of raising doubt about the rapid effort to fly an SP-AS-63 vehicle in four months’ time. After all, nobody wanted to finish hardware for flight if an impending study indicated it was unnecessary.

McMillan ordered the study in response to a statement at the beginning of the year by the United States Intelligence Board (USIB) about the need for a reconnaissance system with five-foot (1.5-meter) resolution and stereo search capabilities. The USIB established intelligence requirements, and none of the systems then in development could meet that requirement. In response to McMillan’s order, SAFSP created an ad hoc committee which eventually concluded that reactivating the E-6 program made the most sense.

Work continued on SP-AS-63, but it began to slow. Officially, the launch date was now July 1963 but it was increasingly doubtful that this goal could be achieved. The SPARTAN experiment had been designed to determine the maximum resolution of the camera, in part by lowering its orbit. This lower orbit limited its ground coverage, and those outside the program criticized its limited coverage. But the bigger problem was that the CIA was still opposed to reviving the E-6 camera in any form that challenged the CIA-managed CORONA.[9]

| SPARTAN was viewed, rightly or wrongly, as an Air Force effort to push the CIA out of satellite reconnaissance. |

The SP-AS-63 project continued to evolve in April and May. Kodak also began evaluating significantly improved versions of the E-6 that would have essentially been new cameras, undermining the argument for flying an experiment using one of the existing E-6 cameras. The momentum of support for the experimental project was lost. By July 9, the NRO formally canceled the SP-AS-63 project, along with any hope of reviving the Samos E-6.[10]

The end of Samos

SPARTAN was always more of an experimental program than an operational one, although it did ostensibly meet some intelligence requirements. But like the LANYARD, it provided overlapping capability with CORONA and GAMBIT and was not strictly necessary. At least LANYARD enjoyed some CIA support, but SPARTAN was viewed, rightly or wrongly, as an Air Force effort to push the CIA out of satellite reconnaissance. Considering that the Samos E-6 had been a more obvious effort to replace the CORONA and thus eliminate the CIA reconnaissance mission, it is not difficult to understand why the CIA was wary of SPARTAN.

The end of SPARTAN was also the end of efforts to save something from the substantial investment in the Samos reconnaissance program. The NRO launched LANYARD satellites three times in 1963, but only the third flight, in July of that year, proved partially successful. Soon LANYARD was canceled as well. Ultimately, some of Samos’ film-readout technology ended up in NASA’s Lunar Orbiter spacecraft. But by 1963, photo-reconnaissance technology had evolved to the point that the legacy systems from Samos were considered obsolete, and camera designers were developing far more advanced systems. SPARTAN was relegated to the footnotes of classified histories.

Endnotes

- Robert Perry, “A History of Satellite Reconnaissance, Volume IIB – SAMOS E-5 and E-6,” October 1973, p. 461.

- Perry, p. 467.

- Perry, p. 468.

- Perry, p. 469.

- Perry, p. 470.

- Perry, p. 474.

- Perry, p. 476.

- Perry, p. 478.

- Perry, pp. 481-483.

- Perry, pp. 484-485.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.