Space policy, geopolitics, and the ISSby Jeff Foust

|

| Biden said that while he didn’t think Putin had decided yet to invade, he expected Putin to do so. “My guess is he will move in. He has to do something.” |

It is not, though, business as usual down on Earth when it comes to Russia’s relationship with the US and the West. For months, there have signs that Russia was massing troops for an invasion of Ukraine this winter. Those concerns have grown ever stronger to the point where some believe an invasion is all but inevitable.

“Do I think he’ll test the West, test the United States and NATO as significantly as he can?” President Joe Biden said at a January 19 press conference, referring to Russian president Vladimir Putin. “Yes, I think he will.” He added later that while he didn’t think Putin had decided yet to invade, he expected Putin to do so. “My guess is he will move in. He has to do something.”

An invasion in the coming weeks would come nearly eight years after Russia entered eastern Ukraine and annexed Crimea. The stakes, though, are higher this time. “This will be the most consequential thing that’s happened in the world, in terms of war and peace, since World War II,” Biden said.

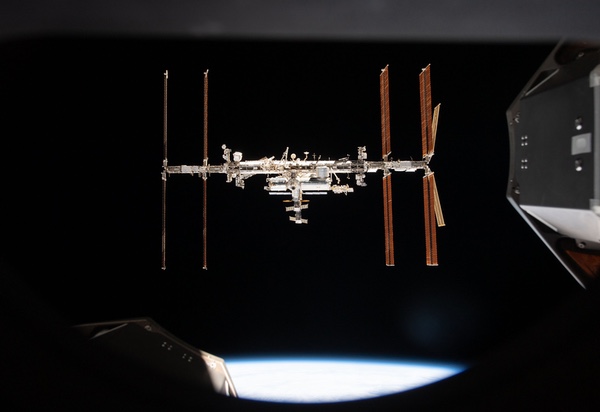

For the space community, the prospect of a Russian invasion of Ukraine raises questions about the future of cooperation between Russia and the West in space, particularly on the International Space Station. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 prompted sanctions by the West. In response, Dmitry Rogozin, then deputy prime minister, threatened to cut off the supply of RD-180 engines used by the Atlas 5 as well as deny NASA astronauts seats on Soyuz flights to the ISS—infamously suggesting that NASA would have to rely on a trampoline to get to the station.

Russia, though, never followed through on those threats: the RD-180 engines kept coming and NASA astronauts kept flying on Soyuz missions. This time around, officials in the US and Europe are trying to look beyond the tensions on the ground as they look to maintain their partnerships with Russia in space.

NASA administrator Bill Nelson, for example, has frequently emphasized the longstanding partnership between the US and Russia in space, one that he argues stretches back to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975. “NASA is in contract with our Russian colleagues all the time because, as you know, we operate the International Space Station together,” he said in a media call January 11 to introduce a new chief scientist for the agency.

He's frequently talked about going to Russia to meet with Rogozin, who is now the head of Roscosmos. (Rogozin cannot come to the United States because of sanctions that stem from his role in the events of 2014.) In the call earlier this month, he reiterated his plans to do so, with Covid playing a bigger factor than a potential invasion of Ukraine.

“I am simply at the mercy of Covid, and until we see a subsiding of this pandemic, I’m not going to be able to go,” Nelson said. “I’m looking forward to personally meeting Dmitry, and in the meantime we’ll continue to talk as frequently as need be.”

| “We want to separate cooperation in space from the bigger political picture on the ground,” Aschbacher said. |

The European Space Agency has to contend with not just potential disruptions with the ISS in the event of a Russian invasion of Ukraine, but also European-Russian partnership on a Mars mission. ExoMars is scheduled to launch in late September on a Proton rocket, carrying the ESA-built Rosalind Franklin Mars rover that will be delivered to the surface of Mars on a Russian platform called Kazachok. That mission was to launch in mid-2020 but missed its launch window because of technical problems exacerbated by the onset of the pandemic.

At a January 18 press conference, Josef Aschbacher, director general of ESA, was not concerned about geopolitics interfering with ExoMars or the ISS. “We want to separate cooperation in space from the bigger political picture on the ground,” he said. “I certainly believe that what happens politically on the ground will not change of the plans towards the launch” of ExoMars.

“The space station is the best symbol of working together because we rely on each other and we need each other, especially for big undertakings,” he added. “I do, honestly, want to underline that in space we do need a long-term cooperation. We need all the forces of space agencies worldwide.”

The terrestrial tensions complicate what is a key time for the ISS. On New Year’s Eve, the White House announced it supported an extension of the ISS through 2030, compared to the “at least 2024” date in current federal law. The announcement was not a surprise—NASA’s long-term ISS plans, and efforts to support development of commercial successors, expected the ISS to keep operating through the end of the decade—but still kicked off formal planning to extend the station’s life.

Immediate after the NASA announcement, ESA’s Aschbacher endorsed the extension, saying he will ask the agency’s member states to back ESA’s participation in the station through 2030, likely at the next ministerial meeting late this year. Canada and Japan are also likely to follow along.

“We’re very happy to see the announcement from the U.S. side. That’s helping the decision process,” said Christian Lange, director of space exploration planning, coordination, and advanced concepts at the Canadian Space Agency, during a panel discussion at the AIAA SciTech Forum January 6. “No one would have expected Canada to make a decision before the U.S. or even ESA or Roscosmos.”

“We were seeking the trigger by NASA to extend the ISS beyond 2024,” said Naoki Sato, exploration lead at the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, on the same panel. “With that trigger, we have just started the discussion for the extension of the ISS.”

Roscosmos, though, has not discussed its intentions about extending the ISS since the White House announcement. In recent months, Rogozin has been dismissive about a long-term extension because of what he said was the growing technical challenges of maintaining the aging station.

“The current agreement is that we’ll keep operating it until 2024. It can, of course, keep flying after 2024, but every next year will come at greater difficulty,” he said during a press conference at the International Astronautical Congress (IAC) in Dubai in October.

| A State Department spokesperson declined to discuss details about a cosmonaut’s denied visa but added that “the United States values the important bilateral cooperation on the International Space Station.” |

There has been greater progress on a near-term issue that ties the US and Russia closer together on the ISS: swapping seats between Soyuz and commercial crew vehicles. NASA has advocated for a barter agreement that would allow NASA astronauts to continue to fly on Soyuz spacecraft in exchange for Russian cosmonauts flying on Crew Dragon and, eventually, CST-100 Starliner vehicles. Such “mixed crews” would ensure at least one NASA and one Roscosmos crewmember would be on the station in the event either Soyuz or commercial crew vehicles were unavailable for an extended period.

While NASA pushed for a barter agreement, Roscosmos was initially opposed, arguing that the commercial crew vehicles were not yet proven. However, at the IAC in October, Rogozin said he was now satisfied. “In our view, SpaceX has already acquired enough experience for us to be able to put our cosmonauts on Crew Dragon,” he said.

The seat barter agreement is in the process of being approved by the American and Russian governments. At a meeting last week of a NASA Advisory Council committee, Robyn Gatens, ISS director at NASA headquarters, said the agreement had completed a review by Roscosmos and was now in the hands of the Russian foreign ministry.

The goal is to have the deal completed in time to allow a seat exchange this fall. Roscosmos announced in December that cosmonaut Anna Kikina would go on the Crew-5 Crew Dragon mission to the ISS, while NASA astronaut Frank Rubio is likely to go on Soyuz MS-22.

A backup cosmonaut for Soyuz MS-22 is Nikolai Chub, who is scheduled to go to the station on the Soyuz MS-23 mission next year. However, Roscosmos announced over the weekend that the US government denied Chub a visa to come to the US for routine training at the Johnson Space Center intended to familiarize Russian cosmonauts with the US segment of the station.

Rogozin told Russian media, and stated in his own social media postings, that he would ask NASA why Chub was denied a visa. The US State Department declined to comment on the issue, noting that via records are confidential under US law. A spokesperson added, though, that “the United States values the important bilateral cooperation on the International Space Station.”

The timing of the visa incident, though, can’t help with either near-term or long-term relations between NASA and Roscosmos on the ISS, or other aspects of international partnership, as geopolitical tensions grow. The State Department over the weekend recommended that Americans not travel to Ukraine, and that Americans currently in the country leave.

Even if the ISS is unaffected by any repercussions from a Russian invasion of Ukraine and responses by the US and other countries, it doesn’t mean space policy won’t be altered. While Russia never followed through on threats to cut off shipments of RD-180 engines, the threat, coming at the same time as SpaceX was suing the US Air Force to win the right to bid on national security launches, reshaped the US government launch market. SpaceX secure the right to compete for military launches and ULA, knowing the RD-180 supply would be shut off sooner or later, moved forward with Vulcan.

The threat of losing access to Soyuz seats, and thus the ISS, helped remove any remaining doubts about the commercial crew program. When SpaceX launched the Demo-2 mission in May 2020 with two NASA astronauts on board to the ISS, it was Elon Musk who said at a post-launch press conference, “The trampoline is working!”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.