Building a commercial space sustainability ecosystemby Jeff Foust

|

| There is growing cluster of companies involved with space situational awareness and eventual efforts to remove orbital debris, moving ahead as fast as funding, technology, and policy will allow. |

Events like Russia’s anti-satellite weapons test in November, destroying a defunct satellite and creating thousands of pieces of debris, exacerbate the problem. At a January 18 meeting of the NASA Advisory Council’s human exploration and operations committee, Robyn Gatens, ISS director at NASA headquarters, said before the test there was a risk a “penetrating collision” of debris with the station once every 50,000 orbits.

“It really had increased our background debris about two times compared to prior to this event,” she said of the ASAT test, with the risk of a collision now once every 25,000 to 33,000 orbits. (The station completes about 6,000 orbits per year.) She played down, though, the threat to the station. “We know how to operate in this environment of increasing debris and we have procedures for dealing with it.”

The space environment, though, runs the risk of becoming like the weather: something everyone talks about but no one does anything about. In the two and a half months since the Russian ASAT test there’s been a lot of discussion about the impact of that test on the ISS and low Earth orbit but little action. At a December 1 meeting of the National Space Council, one official called on nations “to refrain from antisatellite weapons testing that creates debris,” but that has yet to lead to any formal proposals for an agreement of some kind banning such tests.

There’s the ongoing concern about the lack of public progress on implementing Space Policy Directive 3, which in June 2018 gave the Commerce Department civil space traffic management authority. A year into the Biden Administration, the Office of Space Commerce, the small branch of the Commerce Department that would handle that work, still does not have a permanent director.

The lack of government progress, though, has not deterred the private sector. There is growing cluster of companies involved with space situational awareness and eventual efforts to remove orbital debris, moving ahead as fast as funding, technology, and policy will allow.

One part of this commercial space sustainability ecosystem involves improved tracking of objects in low Earth orbit. Many operators complain that the conjunction warnings provided today by the US Space Force are alone not accurate enough to decide whether to perform an avoidance maneuver. Move too often and you deplete fuel that shortens a spacecraft’s life, but ignoring the warnings runs the risk of collisions.

LeoLabs operates several radars around the world, like this one in New Zealand, to track satellites and debris in low Earth orbit. (credit: LeoLabs) |

Several companies are providing space situational awareness data or analysis based on that data. LeoLabs, for example, has a growing network of radars around the world to track objects in low Earth orbit. ExoAnalytic Solutions and Numerica have telescopes for tracking objects not just in LEO but also higher orbits, beyond the reach of conventional radars.

| “We’ve started our technology development focused on the big stuff because, eventually, the big stuff becomes the small stuff through a collision or an explosion,” said Astroscale’s Martin. |

ExoAnalytic showed off its capabilities last week when it was able to track the activities of Shijian-21, a Chinese satellite launched last fall operating in GEO to test space debris removal technologies. During a panel discussion at a Center for Strategic and International Studies webinar, Brien Flewelling ran a video based on his company’s tracking network, showing Shijian-21 in the vicinity of a defunct Chinese Beidou navigation satellite in GEO. Shijian-21 docked with the Beidou satellite and became a space tug, moving well above the GEO belt and drifting west for several days before releasing the Beidou satellite and returning to GEO.

GEO space tugs aren’t new—Northrop Grumman has demonstrated its Mission Extension Vehicle by docking with two separate Intelsat satellites and taking over maneuvering and stationkeeping for them—but unlike that company’s publicized efforts, China had not previously announced plans to dock with and move the Beidou satellite out of GEO. ExoAnalytic added that the docking and move out of GEO took place in a daylight gap in telescopic monitoring, but that the company’s telescope network was able to quickly reacquire the spacecraft.

Other startups are looking to analyze space situational awareness in new ways. During a panel discussion at the 14th European Space Conference last week, Chiara Manfletti, chief operating officer of Neuraspace, described her company’s efforts to apply artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies to SSA data from American and European sources.

The company’s product, she said, is a “personal assistant” intended to give satellite operators more accurate warnings of potential collisions. “Compared to the baseline, she’s already providing 22% less false and positives and false negatives,” Manfletti said of that personal assistant. “For an operator that’s confronted with a potential collision, she tells the operator what is the best maneuver you can do given the asset that you have, the orbit you are in.”

Others are turning to space to track other objects in space. Canadian company NorthStar Earth and Space has proposed a satellite constellation called Skylark that will track objects from LEO to GEO. (Other satellites in the system will carry Earth observation sensors.) NorthStar announced in December that it would set up a European headquarters in Luxembourg after the Luxembourg Future Fund participated in a $45 million funding round, helping support work on the first satellites scheduled for launch next year.

| “Our plan is to offer customers subscriptions to our in-orbit servicing program, like roadside assistance programs for cars,” said D-Orbit’s Rossettini. |

Another company planning to track space objects from orbit is Privateer Space, a Hawaii-based company backed by Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak that has kept a low profile to date. During a SpaceCom conference panel in Orlando January 12, Alex Fielding, chairman and CEO of Privateer, said the company planned to start flying sensors in space this year for tracking space objects.

One application of the data is for high-speed and high-accuracy conjunction services, he said. Another would be to support emerging applications, such as satellite servicing, that require greater precision in the knowledge of space objects’ locations than available today. “Do we have the intelligence and the active tracking capability to close on objects in LEO reliably?” he said.

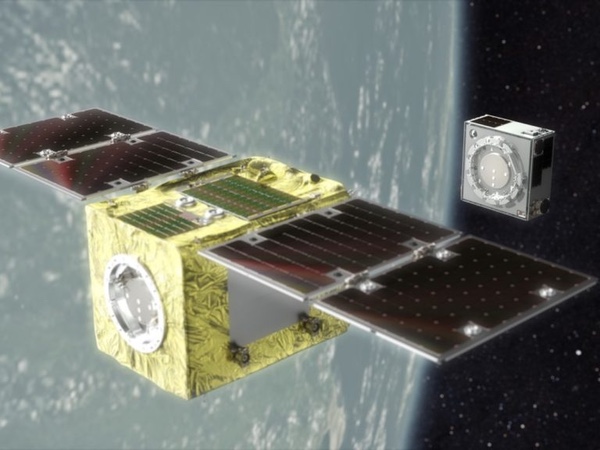

Privateer is cooperating with one satellite servicing company, Astroscale. That company, based on Tokyo but with offices in the US, UK, and Israel, is working on technologies to service and also to deorbit defunct satellites and other debris; the company dubs itself “Space Sweepers.”

“We’ve started our technology development focused on the big stuff because, eventually, the big stuff becomes the small stuff through a collision or an explosion,” said Clare Martin, executive vice president of Astroscale US, on the SpaceCom panel. Astroscale has a contract with the Japanese space agency JAXA for a two-part mission to inspect and, later, deorbit one item of “big stuff” left in orbit, a rocket stage from a Japanese launch.

Astroscale is not alone. A Swiss startup, ClearSpace, is working on a mission to deorbit a payload adapter left in orbit from a Vega launch under a contract from the European Space Agency.

Another entrant is D-Orbit, an Italian company that, to date, has focused on providing rideshare launch services but, as its name suggests, has ambitions to service spacecraft and remove them from orbit. Last Thursday, D-Orbit announced that it would go public by merging with a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC, called Breeze Holdings, raising up to $185 million.

That funding will help it expand into satellite servicing and deorbiting services. “Our plan is to offer customers subscriptions to our in-orbit servicing program, like roadside assistance programs for cars,” said Luca Rossettini, founder and CEO of D-Orbit, in a conference call about the SPAC merger. The company has a contract with an unidentified “major satellite operator” for satellite disposal services, he said, but did not provide details.

That could lead to new applications, such as recycling spacecraft and in-space manufacturing, he said. “The extended capabilities of D-Orbit’s fleet of cargo and servicing spacecraft have the potential to enable new transportation and logistics infrastructure, which will be essential for long-term sustainable space business practices and human expansion in space.”

D-Orbit is betting its future on those new applications. The company reported revenues of just €3 million ($3.4 million) in 2021, but projected those to grow to nearly €1.37 billion ($1.54 billion) by 2025. More than 80% of that total comes from future in-orbit services like satellite servicing and disposal.

| “We need to pick up debris. We need trash trucks. We need things to go make debris go away,” said Maj. Gen. Burt. “I think there is a use case for industry to go after that as a service-based opportunity.” |

Those companies are betting that there will be a robust market for deorbiting services from companies that operate satellite constellations and need to remove satellites that can’t deorbit themselves, keeping their own orbits clear from debris. They’re also looking to governments, like what ESA and JAXA have already done, to fund deorbiting of their own satellites and upper stages.

A Space Force general endorsed such services in a speech at the AMOS Conference for space surveillance in September. “We need to pick up debris. We need trash trucks. We need things to go make debris go away,” said Maj. Gen. DeAnna Burt, vice commander of the Space Force’s Space Operations Command. “I think there is a use case for industry to go after that as a service-based opportunity.”

While she said there was a business case for debris removal as a service, in part to alleviate concerns about dual-use technologies if the military developed a similar capability, there’s been little traction so far on government support for commercial debris removal efforts. SpaceWERX, the space-focused arm of the Air Force technology incubator AFWERX, announced last year “Orbital Prime,” an initiative to support satellite servicing and deorbiting systems, but the funding for now is limited to small grants like those in typical SBIR programs.

Technology development is still critical to this field, something Astroscale is finding out now. The company launched its End-of-Life Services by Astroscale-demonstration (ELSA-d) technology demonstration satellite last March to test technology to capture objects. In August, ELSA-d successfully completed its first major test: releasing and then capturing a small client satellite.

Last week, the company attempted a more ambitious test, with a greater separation between the main spacecraft and the client and with autonomous navigation. However, Astroscale said it “detected anomalous spacecraft conditions” and halted the test before capturing the client. “For the safety of the mission, we have decided not to proceed with the capture attempt until the anomalies are resolved,” the company said, without stating what the anomalies are.

There are policy challenges as well, even if companies focus only on debris from their own countries or countries with whom they have agreements to address liability issues posed by the Outer Space Treaty. For an American company, it remains uncertain who in the federal government would license their activities in order to provide the authorization and continuing supervision required by the treaty.

But companies are optimistic that there is a market emerging for commercial space sustainability services, be it tracking, collision avoidance, or satellite servicing and removal. Monica Jan, senior director of strategy at Virgin Orbit, noted at SpaceCom she previously worked for LightSpeed Innovations, an incubator for space startups. “I recall having many conversations with aspiring entrepreneurs eight to ten years ago trying to come up with a space debris solution. The roadmap for their business case was extremely challenging,” she said. “We’re at a place now where we can help that next generation of startups to solve these problems.”

“I’m an optimist. We messed this up one step at a time,” Fielding said. “I am a believer you can unwind this one step at a time.”

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.