Are space movie studios sci-fi fantasies?by Jeff Foust

|

| Both Cruise’s rumored plans and the upcoming Russian film seem to have convinced people there’s a market for shooting movies in space. |

Those reports did apparently convince the Russians to do their own space movie, called The Challenge, with the cooperation, and maybe financial support, of Roscosmos. A director and an actress flew to the station in October to film scenes of a movie that’s supposed to come out later this year, putting The Challenge in line to become the first feature-length dramatic movie with major parts of it filmed in space (a distinction that’s required for earlier documentaries or Richard Garriott’s short spoof Apogee of Fear.) Take that, Tom Cruise!

Both Cruise’s rumored plans and the upcoming Russian film seem to have convinced people there’s a market for shooting movies in space. Last month, Axiom Space, a company adding commercial modules to the space station that will later become part of a standalone commercial space station, said it had been selected by a company called Space Entertainment Enterprise (SEE) to build an “inflatable microgravity entertainment venue” called SEE-1 that would be attached to its own commercial modules.

According to Space Entertainment Enterprise, the spherical module will be a space studio of sorts. “The module will allow artists, producers, and creatives to develop, produce, record, and live stream content which maximizes the Space Station’s low-orbit micro-gravity environment, including films, television, music and sports events,” it said in a statement.

Space Entertainment Enterprise is an unknown in the space industry. “S.E.E is co-founded by Elena and Dmitry Lesnevsky, media entrepreneurs and film producers, who are producing the first ever Hollywood motion picture filmed in outer space,” the statement helpfully says.

Wait: the first ever Hollywood motion picture filmed in outer space? A link in the press release goes to an Internet Movie Database (IMDb) page titled “Full Cast & Crew: Untitled Tom Cruise/SpaceX Project” The Lesnevskys are listed as producers, along with Tom Cruise and Elon Musk, among others.

If you follow that page to Dmitry Lesnevsky’s IMDb entry, you find someone who produced many movies in Russia years ago, but whose last movie was something called Turnaround in 2016, which cost approximately $27,000 (yes, thousand) to make and had a runtime of eight (yes, eight) minutes. Elena Lesnevsky, meanwhile, doesn’t seem to have produced any movies that have been released according to IMDb.

It makes you wonder, then, why Tom Cruise, one of the most popular and lucrative actors around today, would partner with a pair of obscure producers to do a movie in space. If he really wanted to do this, surely he could find far more experienced producers out there—unless they concluded the cost of filming in space couldn’t be recouped. (Or that the Lesnevskys are being less than forthright.)

We don’t know much else about Space Entertainment Enterprise and their finances. It said in its statement that it has as consultants and advisors “senior media industry figures such as the former Senior Vice President of Sports and Pay Per View at HBO, the former CEO of Endemol Shine UK, and the former Vice President of Technology at Viacom, alongside NYC-based investment bank GH Partners.” It didn’t identify any of them by name, and only said it’s working on raising money.

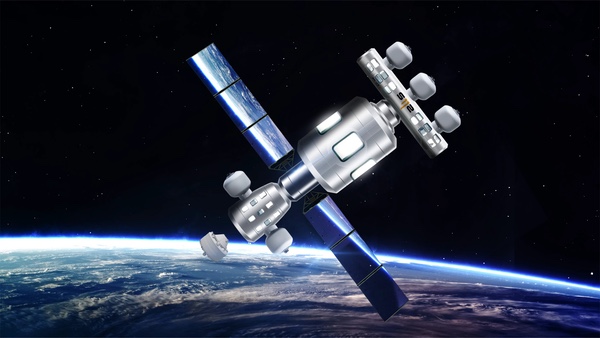

Space 11 will work with Nanoracks on a commercial station for activities ranging from movies to mixed martial arts competitions. (credit: Space 11) |

SEE isn’t alone. The very next day another company, Space 11, said it was working with Nanoracks on “a specialized free-flying space station to service film and TV projects as a dedicated and one-of-a-kind in-space platform akin to a live venue/soundstage.” (SEE might take issue with that “one-of-a-kind” claim: the station would start operations in late 2027, about three years after Space Entertainment Enterprise says its SEE-1 module would be added to Axiom’s segment of the space station.)

| “The final two fighters left will go into space for the final event—a fight beyond our atmosphere. The dramatic and intense series finale will see two combatants fight aboard a custom capsule rocket orbiting Earth.” |

“Exploring space opportunities has been quite eye-opening,” Andrea Iervolino, founder of Space 11, said in the release. He is a film producer who does have a few recognizable movies to his credit, like the 2004 version of The Merchant of Venice.

Interestingly, one such opportunity doesn’t involve movies but extreme sports. Space 11 says it’s creating a mixed martial arts league called MMA ZERO-G and a reality TV series called “Galactic Combat,” which “follows fighters through a 12-episode competition for the opportunity to be the first combatants to fight beyond Earth’s borders.” One of Space 11’s executives is a former MMA fighter, John Lewis.

The show, though, doesn’t appear to depend on the station, according to the statement. Most of the competitors would be eliminated in terrestrial matches. “The final two fighters left will go into space for the final event—a fight beyond our atmosphere. The dramatic and intense series finale will see two combatants fight aboard a custom capsule rocket orbiting Earth.” Converting the interior of, say, a SpaceX Crew Dragon into an MMA ring will be fascinating, to say the least.

It’s technically feasible to build a module that could be used as a film studio or extreme sports arena of some kind. The bigger question is whether it its fiscally feasible. A module or modules like what SEE and Space 11 are proposing could easily run into the nine figures: an amount that can certainly be financed, but one that will take some effort to do so. Investors will have to be convinced there really is a lucrative market for producing movies and other events in space that either can’t be done on Earth or have a premium value for being done in space.

It's not clear moviemaking would meet those criteria. The cost of flying people to space is still very expensive: on the order of $50 million a seat on a Crew Dragon. Thus, even if a movie can get by with sending two people to space—an actor and director/camera operator—that’s already $100 million in costs to absorb on top of all the other expenses associated with a movie. (That two-person minimum comes from the experience with The Challenge, but it was able to use Russian cosmonauts on the station as actors/extras, so a more commercial movie might need to pay for sending one or more additional actors.) That starts pushing a movie’s cost into the high end of what Hollywood is willing to accept.

Then there’s the question of why one would shoot a movie in space at all. The Challenge was set on the ISS: the actress who went to the station played a doctor sent to do emergency surgery on a cosmonaut there. Not many other movies likely require the verisimilitude that shooting in space would offer, given the advances in special effects that are, to most moviegoers, indistinguishable from the real thing. It’s unlikely that the newly released movie Moonfall, about the Moon on a collision course with the Earth, is bombing at the box office because it wasn’t filmed in space.

| These proposals help illustrate a transitional time in low Earth orbit. |

Of course, a movie filmed in space would be a novelty that would attract audiences, especially if an actor like Tom Cruise is involved. But novelties don’t make for a sustainable business model: will people still show up for the third or fifth movie filmed in space, if there’s nothing else more compelling about it? That may be why the companies currently pursuing it are relatively unknown new ventures rather than established studios.

Axiom Space and Nanoracks have little at risk with these ventures: if SEE and Space 11 do raise enough money, they will be happy to build those modules or stations; if not, they’ll move on with their other plans. It does, though, illustrate this transitional time in low Earth orbit. NASA is counting on Axiom, Nanoracks, and others to develop commercial space stations by the end of the decade, allowing NASA and its partners to retire the ISS. NASA, though, doesn’t want to be the only customer of a commercial space station. Its plans, including the cost savings it expects to recoup from being a tenant on a station versus owning and operating the ISS, are based on the agency being a customer, not the customer.

Exactly who those other customers will be is still the subject of speculation. Entertainment, tourism, research, manufacturing and more have all been touted as killer apps for LEO commercialization, but for now there’s precious little hard evidence of how much demand there will be for any of those emerging markets.

One can imagine, in the long term, moviemaking and other entertainment in orbit being a part of the commercial space landscape, particularly as costs of flying people to orbit continue to go down. It’s less clear if it will be a leading or a lagging market, though. Perhaps Tom Cruise will eventually demonstrate whether filming a profitable movie in space is an impossible mission.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.