The Starlink-China Space Station near-collision: Questions, solutions, and an opportunityby Chen Lan

|

| Such events could easily be politicized considering the current geopolitical environment, which does not help solving the real problem in space. |

These encounters were quite special, not only because it happened during the period of increasing Sino-US tension and involved satellites of a high-profile enterprise and China’s proud space station, which would easily trigger sensations in both countries, but also because it’s a rare case that an operational satellite still in control by the ground posed a threat to a crewed spacecraft.

In December, there was only information from the Chinese side and unofficial third-party sources. We do not know what really happened inside SpaceX and possibly in relevant US government bodies. Unfortunately, the recent US note verbale did not provide too much further details either. Instead, it raised more questions.

Such events could easily be politicized considering the current geopolitical environment, which does not help solving the real problem in space. So, this article will focus on technical and management aspects of the event try to sort things out and see what went wrong.

Let’s put all available information on the table.

China’s note verbale to the UN

China filed a note verbale to the Secretary-General on December 6, 2021. It was not reported until about three weeks after its submission. The note verbale claimed two close encounters:

“As from 19 April 2020, the Starlink-1095 satellite had been travelling stably in orbit at an average altitude of around 555 km. Between 16 May and 24 June 2021, the Starlink-1095 satellite manoeuvred continuously to an orbit of around 382 km, and then stayed in that orbit. A close encounter occurred between the Starlink-1095 satellite and the China Space Station on 1 July 2021. For safety reasons, the China Space Station took the initiative to conduct an evasive manoeuvre in the evening of that day to avoid a potential collision between the two spacecraft.

On 21 October 2021, the Starlink-2305 satellite had a subsequent close encounter with the China Space Station. As the satellite was continuously manoeuvring, the manoeuvre strategy was unknown and orbital errors were hard to be assessed, there was thus a collision risk between the Starlink-2305 satellite and the China Space Station. To ensure the safety and lives of in-orbit astronauts, the China Space Station performed an evasive manoeuvre again on the same day to avoid a potential collision between the two spacecraft.”

Independent orbital analysis

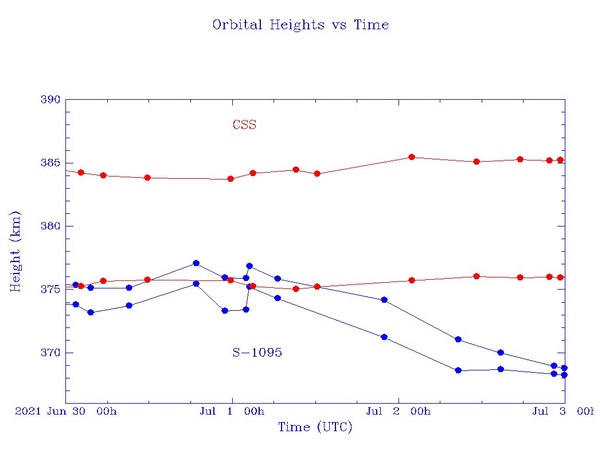

Jonathan McDowell, a renowned and respectable astrophysicist and space activity monitor, was the first one who independently confirmed the accidents based on open orbital data. On December 28, he tweeted his orbital analysis. The following figures show orbits of the Starlink and the CSS in July and October.

Figure 1: The July encounter |

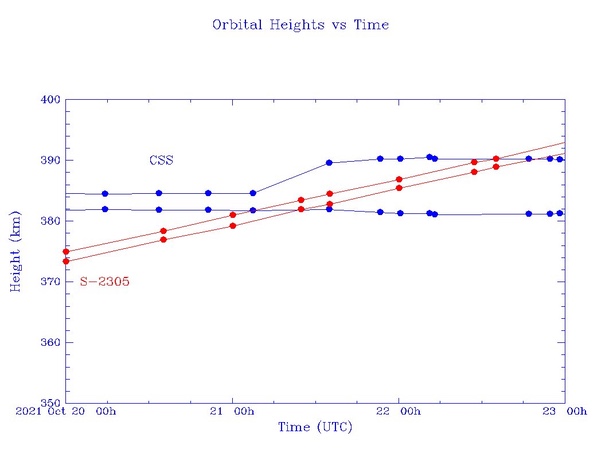

Figure 2: The October encounter |

On January 18, McDowell summarized the events in his Jonathan's Space Report No. 802 with the earlier conclusion further confirmed. He predicted a surprisingly close pass within one kilometer (before the CSS’s avoidance maneuver) in October, although the closest distance in the July encounter was seemingly missed in the published text.

“China has complained to the UN (in UN document A/AC.105/1262) that Starlink sats are buzzing the Chinese Space Station (CSS). Two incidents are mentioned, and analysis of the TLEs confirms that the close passes in question did indeed occur as described.

On Jul 1 at 0950 UTC the CMSEO (zhongguo zairen hangtian gongcheng bangonghsi, China Human Spaceflight Engineering Office) commanded the CSS to make an orbit adjustment to dodge Starlink 1095, which was in the process of lowering its orbit towards disposal; a close (km or less) pass would otherwise have happened at about 1315 UTC. It appears that the Starlink also made a small avoidance burn around the same time, but it sounds like there was no advance communication between SpaceX and the CMSEO about the pass.

On Oct 21 the then-recently-launched Starlink-2305 satellite was orbit raising through the altitude of the CSS and was predicted to pass within 1 km of the Chinese station at about 2200 UTC. The CSS made an orbit adjustment at about 0316 UTC to avoid the encounter. In this case Starlink-2305 does not appear to have made any avoidance burns.”

The US note verbale to the UN

The U.S. filed a note verbale to the Secretary-General on January 28, 2022. It states:

“In the specific instances cited in the note verbale from China to the Secretary-General, the United States Space Command did not estimate a significant probability of collision between the China Space Station and the referenced United States spacecraft:

- Starlink-1095 (2020-001BK) on 1 July 2021

- Starlink-2305 (2021-024N) on 21 October 2021

- Because the activities did not meet the threshold of established emergency collision criteria, emergency notifications were not warranted in either case.

- If there had been a significant probability of collision involving the China Space Station, the United States would have provided a close approach notification directly to the designated Chinese point of contact.

- The United States is unaware of any contact or attempted contact by China with the United States Space Command, the operators of Starlink-1095 and Starlink-2305 or any other United States entity to share information or concerns about the stated incidents prior to the note verbale from China to the Secretary General.”

SpaceX actions

According to the abovementioned February 15 SpaceNews report, SpaceX has worked with the State Department and other US government agencies on getting notifications to China. Bill Gerstenmaier, vice president of build and flight reliability at SpaceX, said during a panel at the AIAA ASCEND conference in November that SpaceX checks for close approaches of its Starlink satellites with the International Space Station and China’s Space Station. “We provide information to the State Department, but I don’t know what happens after,” he said.

| This raises a new question: how close is considered “established emergency collision criteria” as mentioned in the US note verbale? |

On August 6, 2021, SpaceX had a teleconference call with the Federal Communications Commission, discussing Starlink’s safety issues. According to the presentation of the meeting this author obtained, Starlink utilizes an automated collision avoidance system, ingesting data (of space debris etc.) from the 18th Space Control Squadron, and the satellites can autonomously evaluate risks and plan avoidance maneuvers without human input. Humans are still present in an oversight role, as an added measure of safety. Starlink satellites currently default to taking maneuver responsibility for conjunction events with other operators and avoiding the ISS by a wide margin makes it so that no additional NASA operational actions or dedicated monitoring is necessary.

The “Pizza Box”

Based on above information, it can be confirmed that the two encounters did happen and the CSS did perform avoidance maneuvers in both events. But how close were they, after the avoidance maneuver and without such a maneuver? Both China and the US did not provide details, nor did SpaceX. According to the US statement, it seems that the distance did not meet its criteria.

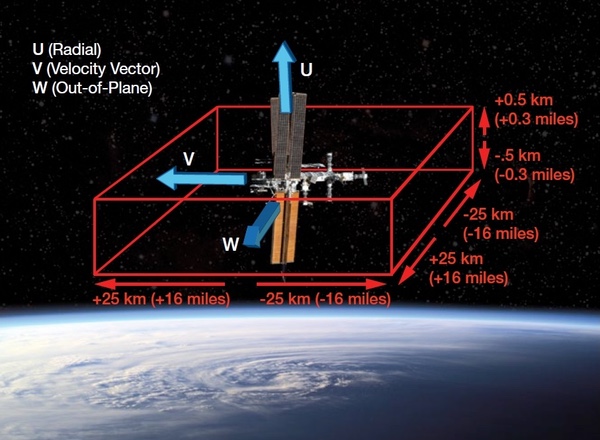

This raises a new question: how close is considered “established emergency collision criteria” as mentioned in the US note verbale? I did some research on this topic. In page 46 of the book Protecting the Space Station from Meteoroids and Orbital Debris (1997) written by the Committee on International Space Station Meteoroid/Debris Risk Management:

“the SSN [author’s note: SSN = Space Surveillance Network] routinely screens the catalog for objects predicted to approach the orbiter within a defined ‘warning box’ approximately 25 km along the track of the orbit (either leading or trailing), 5 km across the track of the orbit, and 5 km out of the plane of the orbit. The estimated 10 to 30 objects per day that come within the warning box are reassessed using a more accurate algorithm to determine whether any come within a ‘maneuver box’ of 5 km along track x 2 km across track x 2 km in the radial direction. If an object does, the ISS may initiate a maneuver to avoid impact.”

Also, in a similar book, Space Shuttle meteoroids and orbital debris protection, published in the same year by the same author, there is an identical definition of these two “boxes.” And there is also a picture showing their size of 50 x 10 x 10 kilometers and 10 x 4 x 4 kilometers respectively.

However, NASA now uses a new, single-level criteria for ISS. The following text is quoted from the NASA website:

“These guidelines essentially draw an imaginary box, known as the ‘pizza box’ because of its flat, rectangular shape, around the space vehicle. This box is about 2.5 miles deep by 30 miles across by 30 miles long (4 x 50 x 50 kilometers), with the International Space Station in the center. When predictions indicate that any tracked object will pass close enough for concern and the quality of the tracking data is deemed sufficiently accurate, Mission Control centers in Houston and Moscow work together to develop a prudent course of action.”

There is no illustration of the “pizza box” in the web page. Fortunately, my Go Taikonauts! colleague Jacaqueline Myrrhe provided me a picture displaying clearly the box. It is from the book The International Space Station - Operating an Outpost in the New Frontier (NASA-SP-2017-634, page 145), published in 2017. However, height of this box is only 1 km, much less than what described by the official web page. Considering the book was published about 5 years ago, I have to assume that 4 km is the updated threshold currently in use.

Figure 3: Illustration of the “pizza box” in the NASA publication (credit: NASA) |

If Jonathan McDowell’s calculation is correct, the predicted position within one kilometer from the CSS (before CSS’s avoidance maneuver) in October was well inside the warning box and the maneuver box used in the past, or the “pizza box” used now. But no emergency notifications were triggered. So, either something went wrong in McDowell’s calculation (in fact, it is still the only result unverified by other sources), or there was something going on behind the scenes.

More questions

There are more questions to be answered. Did SpaceX provide the specific CSS encounter information to the State Department in July and October, as Bill Gerstenmaier said vaguely in November? What is SpaceX’s own criteria for a potential collision? Is it the same as the “pizza box” defined by NASA? Did Starlink’s collision avoidance system take maneuver responsibility and worked as expected during the encounters in July and October? Why was there not any maneuver in the October encounter?

| But we already know a fact: communications between China and the United States on collision avoidance in the human space programs has completely failed. |

On the other side, China hadn’t taken any action for five months after the July incident until it submitted the note verbale to the UN. They continued to keep silent afterwards until media found the note verbale’s existence in late December. Was China waiting for SpaceX’s active notification and did not want to ruin its relationship with Elon Musk?

The biggest confusion appeared in the communication between the two sides. “After the incidents, China’s competent authorities tried multiple times to reach the U.S. side via e-mail, but received no reply,” Zhao Lijian, spokesman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said. While in the US note verbale, it states “The United States is unaware of any contact or attempted contact by China with ... any other United States entity.” Who is not telling the truth?

We will probably know answers to these questions in the future. But we already know a fact: communications between China and the United States on collision avoidance in the human space programs has completely failed. It was very unfortunate. One of reasons for such poor communication, misunderstanding, and even hostility is lack of transparency. We saw it clearly from this case.

Solution and opportunity

The good thing is that both China and the US have expressed a willingness to improve communications and to establish a formal collision avoidance mechanism, a solution that will benefit both sides.

The United States tends to direct communication through bilateral channels, to facilitate efficient and timely sharing of information and coordination of potentially urgent responses. In the note verbale to the UN, it urges all spacefaring nations to work constructively to reduce the risk of collisions between space objects and within human spaceflight activities.

China prefers to discuss and coordinate space related affairs through the United Nations, as shown in this case. But now it is also open to more formal lines of communication with the U.S. on space safety, as SpaceNews reported. “The Chinese side stands ready to establish a long-term communication mechanism with the U.S. side,” Zhao Lijian said.

Transparency is the basis for international cooperation on space collision avoidance. China was often accused of lack of transparency in its space program. While in this case, it released more information than the US side did. SpaceX and the US government agencies need to provide more details about the events happened last July and October to clarify the questions asked above.

| Transparency is the basis for international cooperation on space collision avoidance. |

On February 12, the China Manned Space Engineering Office announced that it has started to publish TLE (Two Line Element) data of the CSS orbit on daily basis for collision avoidance analysis by other parties all over the world. It was probably a precaution taken in wake of the two accidents last year. In any case, it was an encouraging step towards a formal mechanism on space collision avoidance through international cooperation.

To establish such a mechanism, there is a lot of work for spacefaring countries to do. Consensus on maneuver responsibility and working procedure, and the size of the warning box (“pizza box” or whatever) must be reached. Maybe an enlarged second warning box for heavier, larger, and thus more energetic and dangerous spacecraft is also required. As electric-propelled spacecraft like Starlink satellites can change their orbit all the time during ascent and descent, and their orbits are difficult to predict using traditional TLEs, new methods are needed to share their orbit status easily to other parties.

The risk of orbital collision has been increasing over recent years and now has become a sensitive international political issue. But the Starlink-CSS near collision also attracted the public’s attention and prompted an increased awareness of the importance of the risk of collision in space. Thus, it can also be turned into an opportunity if we take actions immediately. I believe that human beings have wisdom enough to capture this opportunity. One has to stay optimistic.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.