A FAB approach to Mars explorationby Jeff Foust

|

| “We have identified opportunities to augment and expand on the critical investment in MSR at a relatively low cost with high potential for community engagement and continuity for a robust Mars Exploration Program,” the report states. |

The decadal survey’s recommendation then was a boon for the prospects for Mars sample return, but had its downsides as well. NASA has focused its Mars program on Mars sample return to the exclusion of other missions to the Red Planet. Beyond the lander scheduled to launch as soon as 2026—but more likely 2028—to pick up the samples cached by Perseverance, the only other NASA Mars missions in development are the International Mars Ice Mapper, a NASA-led mission also likely launching in 2026 or 2028 to map subsurface ice deposits that could be targets of future human missions, and a smallsat mission called ESCAPADE to study the Martian magnetosphere that will launch in 2024.

Mars researchers have been sounding the alarm about this for some time, fearing a loss of momentum as existing missions on and orbiting Mars reach the end of their lives in the coming decade. An October 2020 report by NASA’s Mars Architecture Strategy Working Group argued that Mars sample return should not be seen as the culmination of robotic exploration of Mars. It called for a continued series of missions from small spacecraft up the New Frontiers class, which cost more than $1 billion each, to both continue research in a range of topics and to help prepare for later human missions.

A related effort focused on missions to the Martian surface. Caltech’s Keck Institute for Space Studies (which, yes, goes by the acronym KISS) supported a study last year on “Revolutionizing Access to the Mars Surface” and released that project’s final report last month. It argued that it’s possible to not only send missions to Mars but also land them on the surface for far less than traditional NASA missions, thanks to both new technologies and new partners.

“Mars Sample Return has primary importance for this decade, and nothing in this strategy is intended to replace or delay MSR,” the report states. “We have identified opportunities to augment and expand on the critical investment in MSR at a relatively low cost with high potential for community engagement and continuity for a robust Mars Exploration Program.”

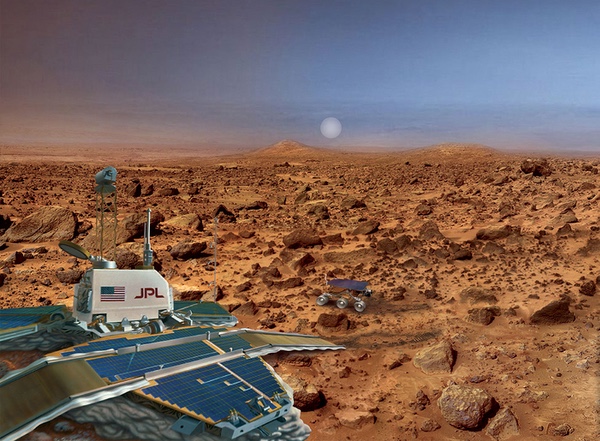

Such missions, ranging from relatively large landers and rovers to small spacecraft designed to make hard landings, could perform a wide range of science. The study didn’t endorse specific mission concepts but instead showed what types of science could be done by a variety of landers, rovers, and aerial vehicles based on the Ingenuity helicopter. Even small hard-landed spacecraft could conduct atmospheric and geophysics studies, particularly as part of a network long desired by some scientists (Mars Pathfinder, launched 25 years ago, was originally MESUR Pathfinder and developed as a precursor for a proposed Mars Environmental Survey, or MESUR, network of landers that was never built.)

Several factors, the KISS report argues, enable the ability to do that science with small spacecraft. Improved technology is one obvious factor, but it alone is not sufficient. “However, assuming an overall NASA budget at Mars similar or modestly higher than present so as to maintain balance in destinations across the solar system, factors in addition to new technical approaches must be brought to bear that fully activate non-NASA stakeholders and their capabilities at Mars,” the report states.

“Technical innovation really needs to go hand-in-hand with multi-pronged strategic elements to increase our cadence,” said Abigail Fraeman of JPL, one of the co-leads of the study, during a presentation about the study at a February meeting of the Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group (MEPAG).

That strategy is an approach called FAB, for frequent, affordable, and bold. Frequent, in this context, means two missions for every launch window. Affordable means missions that fit within a budget envelope that would start at $100–150 million a year through the end of the sample return program, then grow to $250–350 million a year. Bold, she said, means accepting “different balances on the risk-reward spectrum” for missions, including the ability to accept failures of individual missions and learn from them.

“I’ll address what many of you may be thinking: that this looks a heck of a lot like Faster, Better, Cheaper,” she said, NASA’s initiative in the 1990s for more frequent and less expensive missions with a higher tolerance of risk—at least until a series of failures, including two Mars missions, halted it.

The study, she noted, examined Faster, Better, Cheaper’s legacy; an appendix of the report goes into detail about FBC’s brief history. That included a comment from Rob Manning, who was chief engineer on Mars Pathfinder, that the early—and mostly successful—FBC missions found a “sweet spot” in terms of cost and complexity that was lost over time. “With each new FBC mission,” he said, “the complexity and scope per dollar grew, while the personnel experience levels per project shrank.”

“One of the things where we think this is distinguishable from Faster, Better, Cheaper, is its emphasis on the maintenance on a predictable high cadence of missions,” Fraeman said. Another factor, she added, is “changing the implementation and the partnership approaches, looking to these new partners in the emerging NewSpace sector.”

| “I’ll address what many of you may be thinking: that this looks a heck of a lot like Faster, Better, Cheaper,” said Fraeman. |

Those new partnerships are another enabling factor for the strategy outlined in the report. It emphasizes the growing capabilities of the commercial space sector and lowered costs that could allow organizations beyond NASA to fund such missions. “As costs are lowered, mission execution enters the realm of what consortia of universities or private philanthropic organizations can undertake for scientific advancement,” the report states.

One model the report endorses is NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, where the agency buys landing services, but not the landers themselves, from companies. Fraeman said the idea of two missions per Martian launch opportunity was taken from the CLPS program’s plan of two lunar lander missions a year, intended to provide enough demand to support multiple providers. NASA has also embraced risk with the CLPS program with the long-stated “shots on goal” philosophy that assumes not all landing missions will be successful.

The study, though, didn’t simply focus on small low-cost missions. “On the other end of the spacecraft mass spectrum, a major opportunity may exist for enabling large spacecraft at Mars, if the promise of the SpaceX Starship’s 100 metric ton delivery capability is realized,” the report states. Its promised low cost and high payload capacity, including the potential to both land on Mars and return to Earth, “could open up new possibilities for conducting large Mars surface missions in an affordable fashion, and breaking out of the paradigm that large mass must mean large cost.”

An appendix of the report examines the potential for Starship to deliver large payloads to Mars inexpensively and what it means for mission design, such as the use of commercial off-the-shelf equipment that could be modified without worrying about the mass penalty involved. One thought experiment in the report discussed replacing rovers like Perseverance with highly modified electric cars. Even when accounting for required modifications and the cost of the instruments the car-turned-rover would carry, the vehicle could still be one to two orders of magnitude less expensive than a rover like Perseverance, the report concluded.

| “All of us envisioned that this FAB series of missions would be a component of the Mars program, but not the sole program,” Ehlmann said. |

The report included several recommended “near-term programmatic steps” for NASA to implement, such as work to better understand the capabilities and business plans of companies that could support such missions to developing standardized instruments that could be flown on multiple missions. Those and other proposals are likely to come up at another workshop, Low-Cost Science Mission Concepts for Mars Exploration, scheduled for the end of March in Pasadena.

But how, or even whether, NASA will pursue such missions will depend in large part on what comes out of the latest decadal survey. Bethany Ehlmann of Caltech, one of the study co-leads, noted at the MEPAG meeting that the decadal had been briefed on the earlier Mars Architecture Strategy Working Group. “We’re ready to respond to the content of the decadal survey,” she said.

“All of us envisioned that this FAB series of missions would be a component of the Mars program, but not the sole program,” she added. With few future missions currently on the books, though, even a line of small lander missions might sound fab to some scientists.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.