Russia, space tourism, and explorationby Taylor Dinerman

|

| If NASA can maintain the momentum for its planned return to the Moon, the Block DM and its associated Kurs system could become the basis for a commercial cargo transport service. |

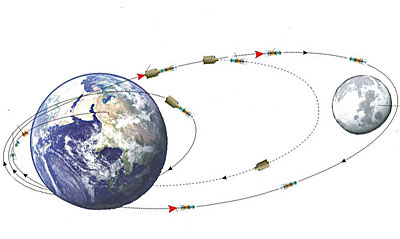

Two of the systems the Russians plan to use in their joint Moon project with Space Adventures are the Block DM upper stage and the Kurs guidance and docking system. The plan is to first launch a Soyuz with the paying customers aboard into low Earth orbit or perhaps to the ISS, and them launch a Block DM with a Kurs system attached to rendezvous with the Soyuz. At the right moment the Block DM would ignite and send the Soyuz into a trajectory that would swing around the Moon and then back for Earth.

In the future, if NASA can maintain the momentum for its planned return to the Moon, the Block DM and its associated Kurs system could become the basis for a commercial cargo transport service. After launch on either a Proton or Zenit rocket, the Block DM/Kurs could rendezvous and dock with a cargo carrier similar to the European ATV or even a modified version of the Italian made MPLM used on the Shuttle and the Russian upper stage could then send the ATV or MPLM into orbit around the Moon where a reusable vehicle launched from the lunar surface, could rendezvous and dock with it and ferry the cargo down to the Moon Base.

While the Block DM can generate enough thrust to get a Soyuz to the Moon, getting into lunar orbit will need a different set of engines which can be made part of the cargo vehicle. Nonetheless, the Block DM looks like it could have a great commercial future as the driving force of a system architecture that would help keep supplies flowing to a future Moon base.

Having an alternative way to get the contents of a pressurized container to the Moon will provide for an extra layer of security for NASA’s lunar base project. The Russians will, no doubt, want to play other roles in this project, but this could be the easiest and the most profitable one. Negotiating those roles on a commercial basis will be difficult, since the US Congress is generally not ready to spend US taxpayers’ money on foreign suppliers. Even if the Congress and the White House agree to fix the Iran Nonproliferation Act problem, there is no guarantee that another issue might come up to interfere with US-Russian cooperation, this is why multiple cargo transport methods will be needed.

| The Russian government’s space program may not be doing much, aside from its central role in the ISS, but Russia’s space companies seem to be healthy and profitable. |

One item that needs tending, too, is to make sure that the Russians, Chinese, and Americans ensure that all of their respective pressurized spacecraft can dock with each other. The Russian Kurs system has, over the years, proven effective: it, or an androgynous version of its docking mechanism, should be the standard interface that all spacefaring nations can agree on. RSC Energia could sell manufacturing licenses to the US, China, and eventually others, with the proviso that however they modify or improve them, they should all be able to fit together in an emergency.

The Russian government’s space program may not be doing much, aside from its central role in the ISS, but Russia’s space companies seem to be healthy and profitable. For Moscow politicians, space is an investment in national pride. Companies like RSC Energia are not only able to build on that pride and on the glamour of the whole endeavor, but have shown themselves to be smart businessmen as well.